- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

This book is the first complete commentary on Marx's manuscripts of 1861-63, works that guide our understanding of fundamental concepts such as 'surplus-value' and 'production price'.

The recent publication of Marx's writings in their entirety has been a seminal event in Marxian scholarship. The hitherto unknown second draft of Volume 1 and first draft of Volume 3 of Capital, both published in the Manuscripts of 1861-63, now provide an important intermediate link between the Grundrisse and the final published editions of Capital. In this book, Enrique Dussel, one of the most original Marxist philosophers in the world today, provides an authoritative and detailed commentary on the manuscripts of 1861-63.

The main points which Dussel emphasises in this path-breaking work are:

- The fundamental category in Marx's theory is 'living labour' which exists outside of capital and which capital must subsume in order to produce surplus-value

- Theories of Surplus Value is not a historical survey of previous theories, but rather a 'critical confrontation' through which Marx developed new categories for his own theory

- The most important new categories developed in this manuscript are related to the 'forms of appearance' of surplus value.

The final part of the book discusses the relevance of the Manuscripts of 1861-63 to contemporary global capitalism, especially to the continuing underdevelopment and extreme poverty of Latin America.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

The central Notebooks of ‘Chapter III’

The production process of capital

- Transformation of money into capital.

- Absolute surplus value.

- Relative surplus value.

- Here the question of accumulation should be included, but, a short time later, Marx speaks in the same terms of the ‘combination’ of ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ surplus value (p. 311).

- Theories of surplus value.

1 Money becomes capital: from exteriority to totality

Notebooks I and II, pp. 1–88; started in August 1861 (MECW.30: 9–171)

1.1 New syllogism: M–C–M (MECW. 30: 9–33)

Then Marx posed first the transcendental ‘passage’ of money into capital. In the first place, as in the Grundrisse, commodities ‘become’ money. Now the radical transition is made. This is a real metaphysical jump. It seems that in June 1858 – in the ‘Index for the 7 Notebooks’ (MECW. 29: 421–3) – Marx already had clearly in mind the question of the ‘transition of money into capital’, in the same systematic place as the ‘passage’ of ‘being into essence’ in Hegel’s Logic. Hence, in the ‘draft of the 1859 project’ written in February or March 1859 (or afterwards, in 1861, according to some authors), there appear references to passages in the Grundrisse on this subject (MECW. 29: 518–32).

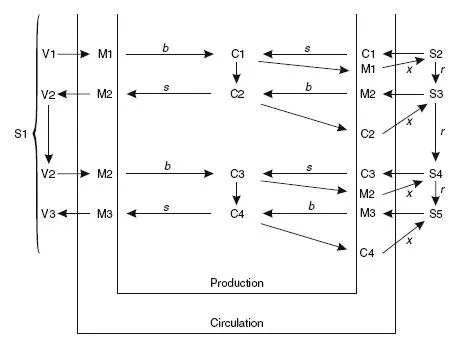

Figure 1.1 ‘Entrance’ and ‘exit’ of money and commodities. ‘Permanence’ of the subject person (capitalist) (S1) and the subject value (V).

Marx wishes to indicate the difference with the syllogism C–M–C. In this case, many subjects enter into circulation as sellers and come out as consumers. Nothing in reality remains nor grows: only money is always in circulation, as means and not as an end, and the circulation is the place where exchange is made. While the M–C–M formula is different:

1.2 Face-to-face encounter of the owner of money and the owner of labour. Creative exteriority (MECW. 30: 33–50 and other texts)4

One cannot ‘pass’ immediately from labour into capital; the mediation of a third moment would be required; that is, value. When objectified labour posits value and the value is capital, such a ‘passage’ can be performed. Convertibility, commensurability or exchangeability between money and capital and between both with labour shall be performed then through the mediation of value. Nonetheless, if this passage is possible, because money and capital are value, it is an absolutely peculiar intervention of the ‘living labour’ (a new concept, not used up to this moment), which creates capital as capital.

- Exteriority of the ‘creative source of value’ from the ‘non-capital’

In the analysis of the exchange between money and labour (exchange between the S1, the capitalist, and S2, the labourer, of Figure 1.1), Marx begins from the ‘non-capital (Nicht-Kapital), non-raw materials, non-labour instrument, non-product, means of non-life, non-money’ (text quoted below). All these negativities already announce that the realm, which is located beyond the being of capital is, however, the same ‘creative’ reality of value – which must not be confused with the mere ‘positing’ of value; namely, capital as capital. If Parmenides said: ‘Being is, non-being is not’, Marx – and here liberation philosophy agrees – by contrast announces: ‘The Being of the capital is value, non-being (non-value) is real’. As affirmation of the exteriority (affirmation of the reality of the non-being) metaphysics transcends ontology (the mere affirmation of being).Certainly considering the text of the Grundrisse, but modifying it (and in the modifications are important corrections of concepts), Marx writes:The separation of property from l...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Editor’s Introduction

- Author’s Introduction

- Part I: The Central Notebooks of ‘Chapter III’: The Production Process of Capital

- Part II: Critical Confrontation of the System of Categories As a Whole: The So-Called ‘Theories of Surplus Value’

- Part III: New Discoveries

- Part IV: The New Transition

- Appendix 1: Correlation of Pages of the Different Texts (Originals and Editions)

- Appendix 2: Exteriority In Marx’s Thought

- Notes

- Bibliography