![]()

1

Introduction

The production and extraction of agricultural products and other primary commodities is among the most basic of human economic activities. It has also long been linked to preoccupations about existential sustainability and future prosperity, so much so that concern with it traditionally lies at the heart of economics and of visions of economic development. In discussions of economics, concern with primary commodities has traditionally been linked to pessimistic visions of the future and, somewhat paradoxically, such pessimism has been rooted in predictions of commodity prices that are either rising or falling.

Economics has long focused on the constraints under which human production and human attempts to cope with scarcity must develop. It is the formulation of such a law of resource constraints that can be seen as one of the early contributions to what was to evolve into modern economics as a social science. It was Thomas Malthus who famously predicted that exponentially increasing human populations would eventually meet the limits imposed by a linearly increasing food supply. At this point food prices will rise as the higher population competes for increasingly scarce resources and the size of the population may eventually be checked by starvation. Rising commodity prices are thus seen as a sign of mounting resource scarcity and eventually of crisis. Modern predictions of resource exhaustion were made in the Club of Rome’s The Limits to Growth study in more recent times.

Some years prior to the Club of Rome’s pessimistic prognosis, another analysis of primary commodity markets anticipated the opposite. In what has become known as the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis, primary commodity prices, which had been falling for some time before the mid twentieth century were predicted to enter a period of permanent decline, thus trapping commodity-dependent developing countries in a position of low income and underdevelopment. While the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis directly opposes the predictions in a Malthusian tradition, they have one common element: a fundamentally pessimistic outlook. It is a peculiar characteristic of long run commodity market analysis that its predictions seem to range from the pessimistic to the apocalyptic regardless of the anticipated direction of change.

Of course, extreme price movements in either direction can have disruptive impacts on related markets or be manifest as symptoms of such disruptions. Economics should highlight mechanisms and development likely to lead to such disruptions and this was probably the objective in exploring the implications of either global resource exhaustion or sustained real commodity price decay. The present volume, however, will concentrate on the latter scenario and ask the empirical question to what extent the concerns originally voiced in the Prebisch–Singer hypothesis, and the more complex dependency theories inspired by it, have materialized.

Economic development can be measured in a number of ways, but one of the main criteria considered consistently has been the level of per capita income attained either in real terms or relative to richer economies. In other words, the conventional focus of economic development is either on per capita income growth in real terms or on convergence in relative terms. Chapter 2 places developing economies in this context and relates questions of growth and convergence to the condition of commodity export dependence. Following a review of the basics of neoclassical growth theory, the question of commodity dependence will be considered in the context of balance of payments constrained growth.

The notion of a tightening balance of payments constraint is itself intrinsically linked to the concept of a persistent net barter terms of trade decline for commodity export dependent economies. Chapter 3 is therefore dedicated to a study of long run trend movements in real commodity prices. This chapter will survey the past debate on empirical trend estimates and statistical trend measurements as well as commenting on the likely magnitude of any inferred trends. In addition to discussing the development of composite commodity price indices, the chapter will look at the evolution of individual, representative commodity price series.

Having covered the background scenario in terms of relevant growth concepts and commodity price trends, Chapter 4 reviews a number of country cases. In these case studies individual country growth and convergence experiences will be juxtaposed with their trade exposure and the evolution of commodity dependence over the years for which data are available. This discussion will draw on detailed trade data to track not only the size of the commodity sector as a whole but the distribution of commodity exports over sub-sectors. These trade data can then be placed in the context of general economic developments as well as the wider country background to assess the nature and persistence of commodity dependence as well as its qualitative change.

The choice of country cases for such a background discussion necessarily has to be selective given the overall reach of the present volume. However, an attempt has been made to present cases that are representative of the changing nature of trading relations for commodity-dependent developing and transition economies in recent years and over the preceding decades of the twentieth century.

The study of individual country cases, the evolution of commodity prices, and their interpretation against a background of balance of payments constrained growth can in their turn be interpreted in a unified setting, and to discuss the question of how the phenomenon of commodity export dependence in developing nations has evolved over time. The final chapter will therefore chart the changing incidence of commodity export dependence. The discussion will proceed to address the correlational pattern between developing country export earnings and economic growth and ask to what extent they are consistent with the notion of balance of payments constrained growth. Both the general evidence on commodity price trends and the country case studies can then be interpreted in this context.

Throughout, the empirical discussion concentrates on data from the twentieth century to the first decade of the twenty-first century. For estimates of long run commodity price trends, data are available going back to 1900, but for most of the subsequent empirical review, data were obtained from multilateral organizations, commonly extending back no further than 1960. At times, data availability is more limited than this. Limited data are a common problem in the study of developing economies, not least because data reporting can be preceded by policy or research interests. Detailed cross-national data on the net barter terms of trade were only included in the World Development Indicators from 1980, after policy interest in their role grew strongly from the 1950s onwards.

A further background fact to bear in mind throughout is the importance of the early twenty-first-century commodity price boom. This strong performance in a number of commodity prices took off in the first decade of the current century, experienced a brief interruption following the 2008 financial crisis, and may be coming to an end at the time of writing. This strong commodity price performance has been attributed to the influence of the Chinese economic take-off and is seen by some as the beginning of an upwards trend in commodity prices more generally.

The topic of primary commodity markets and economic development is likely to remain of interest for some time to come, even if the more extreme predictions in this area have consistently failed to materialize. This book1 will survey the evidence on this topic to date and discuss it against the background of the recent commodity price boom. It aims to show that the focus of relevant research on development and convergence should increasingly be placed on the characteristics of individual country experiences in preference to the analysis of broad global constraints.

Note

![]()

2

Developing country growth and the commodity terms of trade

2.1 Introduction

The evolution of primary commodity prices and commodity supplies can be seen as a constraint on industrial production and developing country growth, with price increases tending to constrain industrial production while tending to increase the unit value of developing country exports. The limits on the viability of industrial production produced by rising resource prices (and the contrary effect of falling prices) are intuitively plausible. The mechanism by which the economic transition of developing countries is constrained by primary commodity prices is less apparent and will be discussed in this chapter.

The chapter will commence by surveying developed and developing country specific growth models before focusing on the perspective offered by Thirlwall’s balance of payments constrained growth model. The focus on the balance of payments constraint will enable an analysis of the role commodity-based export earnings can play in the transition towards a developed economy with a fully capitalized formal sector.

2.2 Modelling growth: the benchmark growth model

Among the various growth models present in the modern applied and theoretical literature, the Solow growth model continues to occupy a position as a benchmark model for empirical work as well as a conceptually simple framework for the introduction to growth theory more generally.1 This chapter will start with a brief review of the model before discussing its drawbacks and limitations in the empirical study of developing country growth.

Some of the Solow model’s core assumptions, such as the constant depreciation rate or the constant savings propensity, are non-trivial simplifications but do not seem to be especially problematic for any particular group of economies. Others appear to make it a priori unsuitable for the study of developing country growth. Among these is the assumption of a closed economy coupled with the assumption of full and efficient employment. The full and efficient employment assumption can be read as implying not only an allocatively efficient market economy, but also an internal market large enough to exhaust gains from specialization. The full employment assumption in turn assumes the existence of an economy which is sufficiently efficient to have absorbed surplus labour from more traditional sectors of the economy – a non-trivial simplifying assumption in the case of many developing economies, which are conventionally prone to exhibiting a dualist economic structure.

The formal model specification only considers three factors of production in its basic form: capital, labour, and technical efficiency. The production function for this model is often cast in Cobb–Douglas form, assuming linear homogeneity such that

which can alternatively be expressed in per unit of labour terms as

where

y =

Y/

L and

k =

K/

L. It is easy to show that this production function has diminishing marginal returns to capital per unit of labour such that

and

, and that

y = 0 for

k = 0. A constant and exogenously given proportion

s of this output is then assumed to be saved in each period, yielding total per unit of labour savings of

S =

sy. Since capital markets are assumed to clear at any point in time (

S∗ =

I), this savings function also identifies actual investment per unit of labour at each level of capital intensity. Equilibrium in this model is produced by interaction with the break-even investment requirement, that is, the amount of investment required to keep the level of capital intensity constant.

In defining the break-even investment requirement, it is usually assumed that a constant proportion δ of the capital stock depreciates in each time period while a constant proportion (n) of the labour force is added to the existing labour force each period. The break-even investment constraint is then obtained as a function of these constant proportions and the measure of capital intensity as

This break-even investment requirement is intuitively plausible: if a given proportion of the capital stock wears out and is written off each period then a corresponding amount of investment is required to replace it and keep the capital stock from falling. If the capital labour ratio (that is, the level of capital intensity) is to be stabilized in addition, while population growth leads to regular additions to the labour force, then additional investment in capital is required to equip each generation of new workers as well as the previous one. This linear break-even investment requirement function will have a unique locus of intersection with the savings function so long as

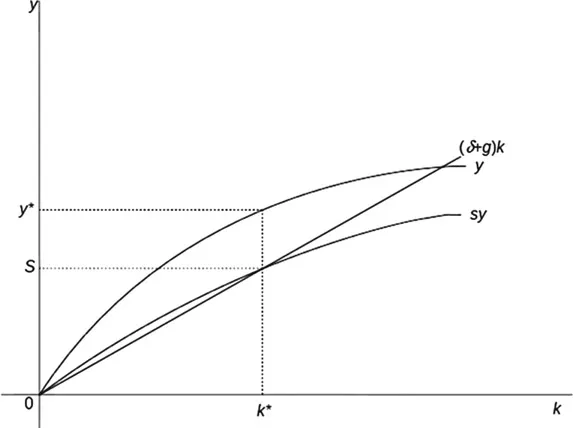

which rules out that the break-even investment requirement function can be consistently positioned above or below the savings function. The equilibrium identified by this model is illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Both the break-even investment requirement function and the production and savings functions pass through the origin. The savings function, being a fixed proportion of the production function, lies under the production function while following its trajectory. A unique steady-state equilibrium is produced at the point where the break-even investment requirement line intersects the savings function. At this point, savings just cover the break-even investment requirement and stabilize the prevailing level of capital intensity.

At any point below the steady-state equilibrium, investment adds more to the capital stock than would be required to stabilize the capital to labour ratio. Capital intensity therefore increases and the build-up of capital adds to the total amount of output and output per unit of labour. As the capital intensity of the production process increases, the diminishing marginal returns property of the production function assures that the net additions to capital per unit of labour become progressively smaller, until they reach a zero value at the steady-state equilibrium. The system described in the Solow growth model will therefore converge to the steady-state equilibrium but will not expand beyond it, since additions to the capital stock beyond the steady-state equilibrium point do not produce sufficient extra savings to stabilize this new, higher level of capital intensity. At the steady-state point, then, output growth from capital accumulation is zero, and all further additions to national output arise from technical progress, i.e. that is, additions to A.2

Figure 2.1 Steady-state equilibrium.

Note: y∗/k∗: equilibrium levels of income/capital per unit of labour.

The Solow growth model has attracted criticism for a number of reasons. One of its main weaknesses is its lack of explanatory power in accounting for long run growth performance: long run growth – in this framework – is a leftover, the Solow residual. In measurement, it is a by-...