![]()

Part I

Unfolding the tripartition

![]()

1

The gap between electoral and liberal democracy revisited

Some conceptual and empirical clarifications

The general objective of Chapters 1 and 2 is to provide a useful conceptualization of the dependent variable of political regime forms. To be more specific, the aim is to arrive at an edifice that sets dissimilar post-communist countries apart while bringing similar post-communist countries together – with regard to the explanandum.1 Reinventing the wheel is seldom advisable and the proper point of departure is the existing literature on democracy or, more generally, on political regime forms.

The contemporary literature teems with new conceptualizations of democracy. Glancing back at the literature of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, this development is striking. In those days, the non-democratic part of the spectrum was where the important political variation was sought, conceptually as well as empirically. Recall Juan J. Linz’s famous effort to provide a conceptual separation between ‘totalitarianism’ and ‘authoritarianism’, Giovanni Sartori’s (1987) protracted endeavours to elucidating ‘What Democracy Is Not’ and Linz and Stepan’s (1978) influential volume on The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes. This non-democratic bias (or pivot) of scholarship held sway even as the new focus on democracy was inaugurated in the 1980s. Witness only the title of Guillermo O’Donnell, Philippe Schmitter and Laurence Whitehead’s path-breaking four-volume work from 1986: Transitions from Authoritarian Rule.

But these days it is the democratic part of the spectrum that is being dissected.2 Peter Mair (2008) has pointed to two reasons lying behind this new scholarly agenda. First, and empirically, the ascendancy of what Samuel P. Huntington (1991) has termed the ‘third wave of democratization’ means that what used to be a relatively homogenous class subsuming empirical referents situated in the north-western quadrant of the world has become a heterogeneous one, containing a large number of quite dissimilar countries encountered in virtually every corner of the globe.3 Second, and theoretically, the literature on regime change has moved to a lower level of abstraction since the early 1980s, highlighting the political consequences of different kinds of democracy rather than merely seeking to explain democracy in toto, as used to be the case.

Hence both the proliferation of ‘democracy with adjectives’ that Collier and Levitsky (1997) so superbly identified and diagnosed a decade ago and hence the relevance of focusing on the new conceptualizations of democracy in the first place.

Most prominently, a number of scholars have advanced an interesting claim: that it is necessary to make a conceptual and empirical distinction between the faces of democracy. This distillation of democracy into electoral and liberal components primarily builds on inductive arguments. For these formerly Siamese twins are seemingly, so the claim goes,4 being torn apart by the third wave. If this is indeed the case, then we do need to embed the electoral vis-à-vis liberal distinction into the conceptualization of the political regime form. Otherwise, we cannot appreciate the dominant empirical dynamics of political change taking place in the world of today. So, let us start out by elucidating and testing this claim.5

Considerations about the gap between electoral and liberal democracy

Almost a decade ago Larry Diamond published Developing Democracy. In this book, he carefully developed a distinction between electoral and liberal democracy and then went on to demonstrate that most of the recent instances of democratization belong in the electoral category, separated by a significant gap from their liberal betters. To quote from his (1999:10) account, ‘[…] the gap between electoral and liberal democracy has grown markedly during the latter part of the third wave, forming one of its most significant but little-noticed features’.

Diamond has not been alone in staking this claim. Guillermo O’Donnell’s notion of ‘delegative democracy’ is very much based on the existence of such a gap, albeit with a narrower empirical context in mind, viz. that of Latin America. To quote from his (1992:7) original working paper on this new concept, ‘[d]elegative democracy […] is more democratic, but less liberal, than representative democracy’. In his later writings, this assertion has been elaborated further. In an attempt to direct attention to the intimate relationship between the state and democracy, O’Donnell (1993:11–12, emphasis in original) thus writes that ‘[…] in many areas the democratic, participatory rights of polyarchy are respected. But the liberal component of democracy is systematically violated’.

Fareed Zakaria has been even more outspoken. In a recent book with the telling title The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, he argues that electoral (termed ‘illiberal’ by Zakaria) and liberal components of democracy have more or less parted ways in today’s world. Quoting one of his (2003:17) trenchant passages: ‘Over the last half-century in the West, democracy and liberty have merged. But today the two strands of liberal democracy, interwoven in the Western political fabric, are coming apart across the globe. Democracy is flourishing; liberty is not’.

A strong theoretical argument does, in fact, favour spelling out the merits of modern democracy with reference to both an electoral and a liberal element. As we shall see, the two dimensions cover distinct aspects of modern democracy. In other words, both regimes that combine the presence of the electoral component with the absence of the liberal equivalent and vice versa are conceptually meaningful. Also, the distinction aptly captures the lineage of democracy. The electoral element dates back to ancient Greece. The liberal element neatly covers the much more recent Anglo-Saxon addition, emphasizing – at the very least – the constitutional qualifications of freedom rights and the rule of law. If a significant gap is separating the two, then it is indeed an important observation.

Be that as it may, the assertions about electoral and liberal democracy of Diamond, O’Donnell and Zakaria are tied together not by common theoretical premises but by inductive reasoning. When looking at the world, they simply identify a gap between the two constructs. This inductive emphasis is no mere coincidence. At the end of the day, the justification for separating the two components must be empirical. If we do not obfuscate the dynamics of regime change in the present world by collapsing the two dimensions, then there is no reason to separate them since this only increases the conceptual complexity. More technically, if we can translate ‘thicker’ concepts into ‘thinner’ concepts without notable validity problems, parsimony dictates that we do so (cf. Gerring 1999).

This is the test then: whether the conceptual separation assists us in capturing the empirical variation – the most salient dividing lines – on, first, the global level and, second, with regard to the post-communist subset. Diamond’s account of the gap is the most ambitious in the literature, theoretically as well as empirically. Hence, I will stick to him throughout this chapter. (See Appendix 1.2 for a discussion of Zakaria’s work.)

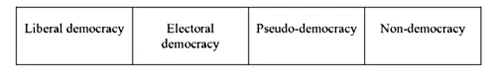

Diamond’s actual conceptualization is, however, less convincing than his point of departure. He goes on to develop a fourfold ‘typology’ of political regime forms, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

As the one-dimensionality of Figure 1.1 indicates, Diamond’s edifice is not what we would normally term a typology. Rather, it is a classification or, at the very most, a matter of ‘quasi-types’ (cf. Lazarsfeld and Barton 1951).6 One may feel inclined to ask ‘So what?’. The consequent conceptual problem is, however, a very tangible one. A pure classification only covers one

dimension; it is an ordering – based on mutually exclusive classes – that refers to one attribute only. In other words, Diamond has drawn a line with ‘very democratic’ on one end and ‘very undemocratic’ on the other end with four types in between.

In doing so, Diamond is unable to carry his distinction between the electoral and the liberal dimensions of liberal democracy over into his actual conceptualization of political regime forms. In his typology, the two dimensions are not conceptually independent of each other. Rather, they are covered by one and the same attribute. Hence, a country moves from electoral democracy to liberal democracy not by adding liberal merits only but by either doing somewhat better with regard to both the electoral and the liberal criteria or doing much better with regard to any of the two. In other words, the two quasi-types or classes are separated by a difference in degree, not a difference in kind.7 This is also obvious when reading Diamond’s subsequent scoring of selected countries, an issue to which I will return. Taken together, Diamond’s conceptualization simply cannot appreciate his own distinction between the electoral and liberal components of liberal democracy.

To be fair, Diamond has somewhat changed his conceptual scheme since the publication of Developing Democracy (see Diamond 2002 and 2003). First, he has proposed to operate with one dimension only, namely the electoral one. Second, he has rebuilt his typology. Third, he has changed the thresholds between the quasi-types or classes. This third point, the modification of thresholds, is only a technicality, albeit a very pertinent one. (I myself will mention and adhere to it later on.) But let us discuss the ...