![]()

1 Introduction

Post-war Japanese economic

development in a global perspective

Koichi Hamada, Keijiro Otsuka, Gustav Ranis, and Ken Togo

1 Introduction

Some 65 years have passed since the end of World War II. It is timely to reflect upon this short but curious Japanese economic history, beginning with the extreme hunger and poverty in the late 1940s, followed by quick recovery and “miraculous” growth since the late 1950s, to the first oil shock in 1972, slow growth in the rest of the 1970s and 1980s, and finally almost complete stagnation over the last two decades. Why has the Japanese economy experienced such a unique development path? Will the Japanese economy continue to stagnate over the coming years? What must Japan do to regain its growth momentum? What lessons can other high-performing Asian economies learn from the Japanese experience? What roles should Japan play in international political and economic arenas, given its unique history of growing from a poor country to a rich country? This volume represents an attempt to provide answers to these questions.

Needless to say, providing clear-cut answers to such critical and broad issues is a formidable task for any single researcher. Thus, we organized a project on the post-war Japanese economic development experience by inviting a variety of researchers with diverse expertise on the key economic issues critical for a proper understanding of post-war Japanese economic development. We address different issues but share a common fundamental hypothesis, namely: “Japan successfully developed the economic institutions conducive to effective learning from abroad in the early post-war period but failed to construct a new economic system designed to innovate on the world technology frontier.” In other words, the success in the “miraculous growth” period led to over-confidence and, hence, complacency when major reforms of economic institutions were called for. Thus, the Japanese economic system is still efficient in imitating foreign technologies but grossly inefficient in creating its own new technologies.

At the outset, we have to emphasize that no institutions are unchangeably efficient at various stages of economic development. When the economy is at a low-income stage, it is probably the best strategy to introduce, imitate, and adapt foreign technologies. Ample evidence is provided by the pre-war Japanese experience and the post reform experience in China (Otsuka et al. 1988; Otsuka et al. 1998). In order to support such a catching-up process, we have to develop institutions useful for learning from abroad. A good example is life-time employment, which is conducive to enterprise growth to the extent that the work experience is an effective means to learn and introduce ideas from abroad. Since employment is assured, a worker has a strong incentive to learn firm-specific knowledge and ideas. This was the case in Japan during the high growth period. Yet, once such a catch-up process is over, enterprises in such a high-income country as Japan must develop their own world-class technologies based on frontier scientific and technological knowledge. Thus, the long-term employment system may no longer be appropriate for such enterprises because advanced knowledge must be constantly introduced from outside the enterprises. It should also be noted that imitation and adaptation can be made by high school, vocational school, and university graduates, but major innovations, which may bring about creative destruction, can usually only be made by high talent manpower PhD holders. In other words, while strong high school, vocational school, and college systems are needed in the catch-up process, strong graduate schools are needed in the process of creating new ideas. The point we would like to emphasize here is that Japan still adheres to a life-time employment system primarily for university graduates, when Japan actually needs far more competent scientists, engineers and management specialists who have completed high quality graduate training.1

While leaving the tasks of validating the basic hypothesis to each of the chapters that follow, we would like to present in the rest of this introductory chapter a simple comparison of growth paths of per capita GDP from 1950 to the present among developed countries and high-performing East Asian countries in order to develop a proper global perspective on the development experience of the postwar Japanese economy.

2 A comparison of development experiences

It was Gerschenkron (1962) who first pointed out the utmost importance of technology import for the development of less developed economies. By now this view has been widely accepted by development economists and other experts. Indeed, the Japanese development since the Meiji era provides a vivid example of rapid economic development based on technology imports (e.g., Ohkawa and Rosovsky 1973; Otsuka et al. 1988). In their textbook on development economics, Hayami and Godo (2005) argue that successful technology transfer from developed to less developed economies is the key to the successful development of the latter. It must be emphasized here that the technology import or technology transfer refers not only to the introduction of new “technology” but also to the transfer of management knowledge and institutions, such as the financial systems, educational systems and management institutions, as well as the employment system, that make it possible to introduce new technologies. This is why this book includes several chapters which address the issues of the relationship between institutions and development.

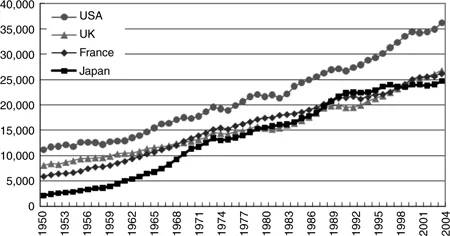

If technology import is the key to growth, the faster the economic growth, the larger the technology gap between developed and developing countries. Although it is difficult to measure that technology gap, it is reasonable to assume that it can be roughly measured by the gap in per capita GDP. Figure 1.1 shows changes in PPP-adjusted real per capita GDP in the United States, United Kingdom, France, and Japan in the period 1950 – 2005, based on the Penn World Tables (see Penn World Table website).

Several important observations can be made. First, when per capita income in Japan was substantially lower than in the advanced western nations, particularly over 1960 – 1973, its growth rate was high. But when it came close to that of Europe, the growth rate slowed down considerably. Such growth patterns can be seen as the result of catch-up growth based on the importation of foreign technologies.

Second, since Japan caught up with the United Kingdom and France, or even surpassed the latter around 1990, the economy has really stagnated in contrast to the slow but steady growth of the United Kingdom and France. Qualitatively the same observation can be made based on the comparison of Japan with Germany and Italy. Thus, it is no exaggeration to argue that the Japanese economy, alone among developed economies, has suffered from a long-lasting “disease.” In this connection it is worth emphasizing that, although the UK economy had been stagnant for nearly a decade prior to the early 1980s, its rate of growth has increased significantly since then. Most likely the “British disease” was cured by the Thatcher reforms, which aimed to liberalize the economic system.

Third, and most importantly, although Japan caught up with the United States to some extent during its high growth period, per capita income in the United States has remained remarkably higher than in the other three countries, and the income gap between the United States and Japan has been widening in recent years. Most of the contributors to this volume have the experience of living both in Japan and the United States. All of us agree that the Japanese are in general harder-working, better educated, and more cooperative than Americans, which, we believe, are valuable traits in modern production systems and service activities. We also fully agree that major differences lie in the development of frontier industries in the United States based on the frontier knowledge of both the natural and social sciences which are supported by strong graduate schools. While it is true that the current world economic crisis was triggered by the inappropriate application of excessive financial engineering, the fact remains that the United States succeeded in developing frontier industries including IT and bio. The quality of graduate training in the United States is outstanding, far exceeding the level in Japanese universities. Most, if not all, of the internationally prominent Japanese economists have been trained in the graduate schools of the United States. Furthermore, in the United States, many CEOs of private corporations, top government officials, and leading politicians have obtained their graduate degrees, unlike in Japan where few such leaders have been trained in graduate school. In short, the United States overwhelms Japan in the accumulation of the highest quality human capital.

Figure1.1 Changes in real per capita income among developed countries.

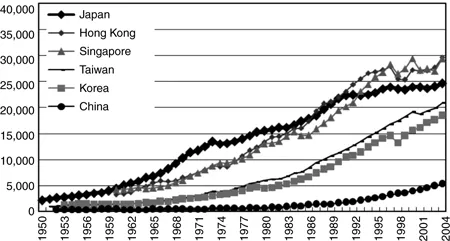

It is also instructive to compare the Japanese experience with those of the four Asian Tigers and China (see Figure 1.2). There is no question that not only Japan but also Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Korea, as well as China, have grown successfully based on technology imports (World Bank 1993). The question is whether, like Japan, they grow rapidly only when a sizable income gap exists or, unlike Japan, they continue to grow even when it doesn't.

It is striking to observe from Figure 1.2 that PPP-adjusted per capita income is higher in Hong Kong and Singapore than in Japan. Like Japan, these are resource-scarce economies and their size is small. Their economies are less regulated than Japan's, however. These economies began their high economic growth roughly ten years later than Japan. Interestingly, their growth rates slowed down considerably after they had caught up with Japan in terms of per capita income in the 1990s. Such growth patterns are consistent with the catchup hypothesis based on technology imports.

Figure 1.2 Changes in real per capita income among East Asian countries.

Taiwan and Korea commenced their rapid growth more than ten years after Hong Kong and Singapore. These economies are still growing rapidly, as they have not caught up with the per capita income level of Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore. It is also important to note that their high growth periods are longer, as the income gap was wider when they began growing. Based on the experience of Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, Taiwan and Korea will continue to grow rapidly for a short while and then stop growing as fast once they complete the catching-up process.

It is no wonder that per capita GDP in China has been growing as fast as 10 percent per year for the three decades since 1978, considering the fact that its per capita GDP was only one-fifth of the Japanese level, even as late as 2004. The four Asian Tigers and Japan also grew at the rate of 10 percent per year during their respective high growth periods. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that China will continue to grow at the rate of nearly 10 percent for the coming decade and somewhat beyond until it catches up with the other five East Asian countries.

3 Scope of the book

Having found a strong indication that, while Japan caught up quickly with the western nations, based on technology imports, its economy has since been stagnant for nearly two decades. We would like to explore the institutional factors affecting the success and failure of the economic development of the Japanese economy during the entire post-war period. We will also attempt to draw useful lessons from the Japanese experience for other high-performing Asian countries which are likely to face similar problems in the near future. Being an advanced country, Japan ought to support the development of low-income economies and contribute to the regional security of Asia. Thus, we review and assess the Japanese ODA policy and the security policy based on the so-called “Yoshida Doctrine” by which Japan endeavored to achieve economic prosperity without allocating large government budgets to the military.

Needless to say, we believe that, in principle, no governmental market interventions shall be necessary if markets work competitively. The economic policy issue arises when markets fail, i.e., it becomes potentially desirable that the government take corrective action in such cases. But government failures are also ubiquitous, suppressing the function of markets rather than supporting or complementing them. In Japan many people believe that economists in the United States advocate reliance on the market mechanism without any regard to possible negative consequences. This is obviously a problem. The authors of this book, like most economists, believe that government interventions are needed where markets do not work well, for efficiency, growth, and social justice reasons (e.g., Shleifer 2000). Particularly after Japan's economic crisis, an increasing number of Japanese people seem to believe that the market mechanism is harmful not only with respect to economic efficiency but also with respect to economic welfare and distributional justice. Such beliefs, however, are largely groundless.

In this book the authors ask what the major market failures are in the context of the post-war economic development of Japan. We believe that such failures arise from imperfect information and distortions in financial markets and the imperfections of the market of useful information and knowledge. It is known that rates of return to schooling are generally high primarily due to the inability of individuals to obtain the credit for investing in education. Since the quality of human capital is the key to sustainable development, such inadequate investment in human capital likely leads to slow economic development. Similarly enterprise managers may not be able to invest in profitable projects due to poor access to financial markets. Even if they invest in the creation of useful new production methods and management systems, they may not be able to reap the full benefits of the investment, due to imitation by others. Thus, social benefits may exceed private benefits and the gap between them thwarts the private incentive to invest in innovations.

Chapters 2 and 3 are concerned with the industrial policies that correct market failures. Chapter 2 addresses the issue of the infant industry protection policies as a case in which government intervention can lead to the development of industries. While this issue itself is old, the novel contribution that this chapter makes to the literature is that it sheds new light on the process by which the Japanese automobile industry has grown, beginning with the protectionist policies afforded to “infant” enterprises in the pre-war period. Chapter 3 attempts to explore the advantages of industrial clusters for industrial development in the light of the Japanese experience. Industrial clusters play a critical role in economic development, not only in the history of advanced economies, including Japan, but also in contemporary developing economies. The authors of this chapter argue that it is what may be termed multi-faceted innovations in technology, management, and organization that lead to the significant modernization of industry. Yet, due to imitation markets fail so that prudent government policies to support cluster-based industrial development can be justified.

Neither infant industries nor cluster-based industries can grow well if financial markets are not working effectively. Chapter 4 assesses the positive role played by the main bank system of Japan during the successful catch-up process before the mid-1970s but finds that this system became an obstacle to sustained growth afterwards by leading to a flawed incentive mechanism when a lending bank official hesitates to cut back unsuccessful lending because it hurts his or her reputation by revealing the failure of outstanding loans. Thus, (inherently) non-performing loans invite additional non-performing loans. This is the zombie loan syndrome that allegedly has prolonged Japan's financial troubles. As the economy approaches the world frontier in technology, investment risks are bound to increase and, hence, it is preferable to share such risks through stock and corporate bond markets rather than relying on the risk absorption capacity of a small number of main banks. Yet, the financial system of the Japanese economy d...