- 282 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Race and Economic Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century

About this book

Examining the crucial topic of race relations, this book explores the economic and social environments that play a significant role in determining economic outcomes and why racial disparities persist. With contributions from a range of international contributors including Edward Wolff and Catherine Weinberger, the book compares how various racial g

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Race and Economic Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century by Marlene Kim in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Racial economic disparities in the twenty-first century

Marlene Kim

The United States has witnessed a sea change in race relations during the past century. One hundred years ago the Chinese were barred from entering the United States, and even at mid-century there were disenfranchised black voters and racially segregated schools, movie houses, city buses and workplaces. Worse, most of society condoned these practices. But the laws and practices that blatantly excluded racial groups have not been practiced for over two generations. Moreover, attitudes have changed, so that equal opportunity is what most Americans prefer. But has the United States achieved equal opportunity by race? Or do barriers remain? This book aims to answer these questions by examining racial and ethnic disparities in economic opportunity and achievement in the United States.

Undisputed by many scholars is that much progress has been made. The blatant racial segregation and Jim Crow laws that survived through the middle of the twentieth century reflected the assent of the general public, which supported segregation and unequal opportunity by race. For example, in the 1940s, two-thirds of white Americans supported racially segregated schools, a majority favored racially segregated public transportation, and most agreed that whites should have preference over blacks in obtaining jobs (Bobo, 2001). In 1954, nearly all (94 percent) of white Americans disapproved of racial intermarriage and a substantial number (44 percent) said that they would move or consider moving if a black family lived next door to them (Kornblum, 2004).

Times have changed. Today most Americans reject racial segregation and believe that there should be equal access to jobs regardless of race (Bobo, 2001). Most also approve of interracial marriage and state that they prefer to live in racially integrated neighborhoods (Gallup, 2004).1 Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians now serve in Congress, as Cabinet members, governors, and CEOs of corporations.

But there are telltale signs that progress remains incomplete. A majority of whites believe that blacks and Hispanics are less intelligent, more prone to violence, and prefer to live off welfare compared to whites (Bobo, 2001). Twenty percent support state laws that would ban interracial marriage (Bobo, 2001). And although racially segregated schools are now prohibited by law, schools have been re-segregating by race since the early 1980s, with the result that they are more segregated by race today than they were 20 years ago (Orfield and Yun).

Even in the twenty-first century, almost half of blacks and two out of five Hispanics and Asians have experienced discrimination because of their race or ethnicity (Washington Post et al., 2001). Blacks and Hispanics report high levels of racial discrimination in employment or housing (Chicago Sun-Times, 2003; Gallup, 2004; see also Washington Post et al., 2001), and many say they experience unfair treatment in their everyday lives: at stores, at work, when dealing with police, when using public transportation, or while in restaurants or other places of entertainment (Gallup, 2004). Different treatment by race is recognized as a fact of life: even most white Americans believe that society treats whites better than blacks (Gallup, 2004).

Yet despite this acknowledgement, many white Americans believe that blacks have attained equality of achievement and opportunity. Many whites assert that blacks are doing better or equally well as whites regarding jobs, their educational levels and access to health care (Washington Post et al., 2001).2 Seventy-one percent of white Americans believe that blacks have more or the same opportunities in life as whites, and three-quarters that blacks are treated fairly (Washington Post et al., 2001; Gallup, 2004).

Not surprisingly, racial and ethnic minorities have a less sanguine view. Far fewer believe that they have the same opportunities as whites (Washington Post et al., 2001), with blacks the most pessimistic about their own opportunities and those of other racial and ethnic groups as well (Washington Post et al., 2001; Gallup, 2004). For example, only 38 percent of blacks believe that blacks are treated fairly, and only 24 percent believe that they have the same opportunities as whites—a sharp contrast to the overwhelming majority of whites cited above (Gallup, 2004; Washington Post et al., 2001). While most whites believe that Hispanics and blacks have the same job opportunities as whites, most blacks and Hispanics disagree (Gallup, 2004). Only one-third of blacks believe that black children’s educational options equal those of their white peers, compared to two-thirds of whites (Washington Post et al., 2001; Toppo, 2004). And while a majority of whites say that most of the civil rights goals of Martin Luther King Jr have been achieved, fewer than onethird of blacks and Hispanics concur (Kornblum, 2004; Gallup, 2004).

An overview of the economic status of racial groups

What can account for these racially disparate views? Have racial and ethnic minorities attained equal achievement and opportunity, or do barriers still exist? To answer these questions, it is useful to gain a basic understanding of the economic status of various minority groups. This section examines whether blacks and other minority groups are as well-off as whites regarding their education levels and jobs, as many whites believe (Washington Post et al., 2001). It also reviews other economic disparities, the theoretical debate regarding why these disparities exist, and the contribution of this book to these important debates.

Table 1.1 Educational attainment by race

Table 1.1 shows education levels by race. It can be seen that Asian men and women are more likely to attain a college degree than whites, and Asian women are more likely to hold graduate degrees than even white men. In contrast, blacks and Hispanics are far less likely to graduate from college and graduate schools. Since education level serves as a prerequisite for many jobs, these differences have important implications for the jobs one can perform. Thus it is not surprising that the relatively higher education levels of Asians afford them access to many higher-paid jobs.

As Table 1.2 reveals, Asian workers are over-represented in business, math, sciences and health care practitioner occupations. But they are also over-represented in lower-paid jobs like food preparation, personal care and production. These disparate occupations reflect the diversity of the Asian population (see Chapter 7 of this book), with Asians of Far East descent attaining higher education levels and relatively high-paid jobs, but Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders and those of Southeast Asian descent unlikely to have college degrees and working in relatively low-paid jobs.

In contrast, black and Hispanic workers are largely absent from high-paid jobs but over-abundant in lower-paid ones. Missing from management and the higher-paid professional jobs in math, engineering and the sciences, a large percentage of blacks and Hispanics work instead in food preparation, personal care, production, and buildings and grounds cleaning and maintenance— all relatively low paid. When they hold professional jobs, black workers work in those that are relatively low paid, such as health care support and community and social services. Black workers are also over-represented in protective service jobs, while Hispanic workers are over-represented in construction, farming, forestry and fishing jobs. Two-fifths of all farming, forestry and fishing workers and one-third of building and grounds cleaning and maintenance workers are Hispanic. All of these are relatively low paid.

Table 1.2 Occupation by race

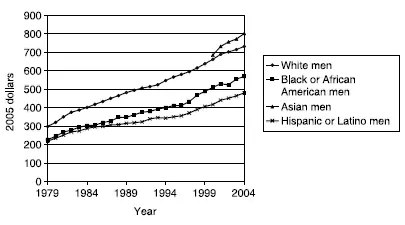

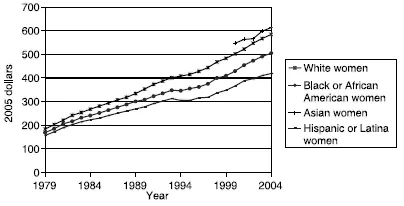

Predictably, these occupational patterns result in earnings differences. As Figures 1.1a and 1.1b show, blacks and Hispanics have lower earnings, on average, than other workers, while Asians have higher. Among full-time workers, black men earn three-fourths the wage of the average full-time white male worker, while Hispanic men earn two-thirds. The racial gap for women is smaller: black women earn 85 percent of the average white women’s earnings; Hispanic women earn about 70 percent. But in addition to these racial gaps, women of color also face gender gaps (Kim, 2006). The result is that they earn much less than white men: black women earn approximately 70 percent of white men’s average earnings; Hispanic women close to 60 percent; and Asian women 80 percent.

Figure 1.1a Median usual weekly earnings, men.

Note: Data are for full-time workers in constant (2005) dollars.

Source: http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table16–2005.pdf.

Figure 1.1b Median usual weekly earnings, women.

Note: Data are for full-time workers in constant (2005) dollars.

Source: http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table16–2005.pdf.

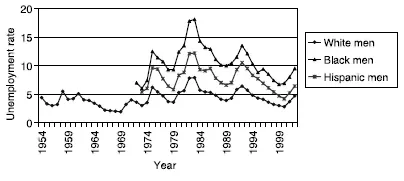

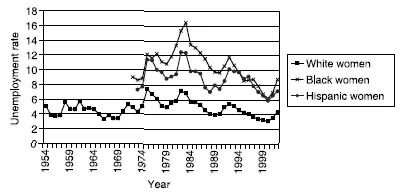

In addition to earning less than whites, blacks and Hispanics also have higher unemployment rates. Their unemployment rates are twice that of whites (see Figures 1.2a and 1.2b), and this difference has persisted for decades.

The combination of having lower earnings and higher unemployment rates contributes to much lower income levels for blacks and Hispanics. As Figure 1.3 indicates, although income for all racial groups has increased for 30 years, black and Hispanic families remain far behind. These families receive 60 percent of the income of white families. Family income for Asians remains slightly above that of whites; this is consistent with their higher earnings levels and the fact that they have more earners per family (see Chapter 7 of this book).

Figure 1.2a Unemployment rates of male civilian workers by race.

Note: Data include civilian workers ages 20 and older.

Source: US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2001 and 2004) Handbook of US Labor Statistics, Table 1–29.

Figure 1.2b Unemployment rates of female civilian workers by race.

Note: Data include civilian workers aged 20 and older.

Source: US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2001 and 2004) Handbook of US Labor Statistics, Table 1–29.

Consequences of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Race and Economic Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Racial economic disparities in the twenty-first century

- Part I: Racial differences in wealth, earnings and work

- Part II: The economic and social environment and implications for racial inequality