Introduction

Economic reform in China has been underway for more than three decades. Today Chinese society is very different in a number of ways to that of 30 years ago. Considerable attention has been paid to macro-level changes, both the positive achievements of rapidly growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP), increasing foreign investment and trade, and growing foreign reserves, as well as the negative problems of increasing disparity of development between urban and rural areas and coastal and inland areas, environmental degradation, and unsustainable development practices. We also know a lot about changes at an individual level: incomes and well-being have improved but at a cost of a widening gap between rich and poor, and worker dissatisfaction and unrest.

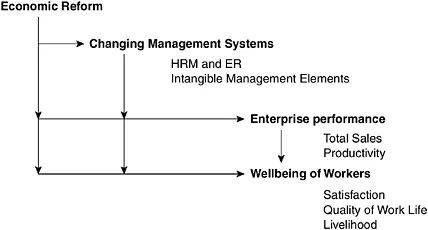

This book is designed to illustrate how these two levels of change are related, and to demonstrate how economic reform has influenced working life. In particular, we focus on work: how economic reform has driven changes in management systems, and how these have influenced the performance of enterprises, worker satisfaction and the workers’ households and livelihoods. What happens to workers over the process of reform depends not only on the actions of the central government but also on the manner in which those actions are interpreted by managers.

Our framework of analysis is illustrated in Figure 1.1. We begin with reform, by which we mean changes to the rules governing business operations (for example, laws about employment relations, about the ownership of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or about competition) and to the cost, delivery and availability of such community services as health, education and housing. These reforms, we argue, have led to changes in the management practices of enterprises – both their human resource management (HRM) and other forms of intangible management. But management practices have changed only slowly and only in some enterprises, and there has been little corresponding change to the role of unions within workplaces. Nevertheless, we do find that the working conditions of people and their satisfaction with conditions both depend on forms of intangible management, especially what we denote as soft management. (Of course, different categories of people – locals/migrants and young/old – do experience these new workplaces differently, or perhaps are treated differently in them.) Furthermore,

we find that both the adoption of new forms of management and the satisfaction that workers feel with their jobs influence the performance of enterprises, though this does depend on the context of the enterprise (by context, we mean the industrial sector, the degree of competition and the location of the enterprise). That is to say, the well-being of workers, both at work and within the households of which they are members, has been substantially affected by the path of reform. The principal routes of this effect are satisfaction at work; the time spent at work, in commuting and on household chores; the changes to costs of living induced by social reforms; and of course, income. By this argument, illustrated in Figure 1.1, and the evidence we present, we link the paths of economic reform to the performance of enterprises and the well-being of workers.

Research sites and data collection

The book is based on a study of 228 employees in 38 enterprises in six locations across China. In each enterprise one manager and five employees (in total, three men and three women) were interviewed in order to gauge the perceptions of both employers and employees. The interviews were conducted in 2004 and sought information about current management practices as well as changes in these practices, enterprise performance and workers’ well-being over the period 1998 to 2003.

The people who work in China’s enterprises are often employed under a variety of employment situations. Many of these workers are local citizens, or migrants with work permits, who work for registered enterprises and are thus normally covered by China’s labour and corporate laws. Some, however, are own-account workers, often migrants from rural areas who seek a foothold in a larger city, while others are unregistered migrants, working in smaller or medium-sized enterprises, who often do not have the protection afforded to workers in larger enterprises. The book is about the former group: formal (registered workers, either migrants or

local citizens) working in formal industrial enterprises (registered companies) in large cities. We do not discuss the issues related to work in the informal sector or the issues associated with employment outside the large cities.

As economic development in China has been uneven, we selected six locations throughout China that we felt reflected this diversity (see Figure 1.2). The first two locations are Beijing and Hangzhou, which are developed regions with high levels of economic development and up-to-date management systems. Beijing is the national capital with the most advanced infrastructure and technology in China. Hangzhou is a traditional economic centre and provincial capital of Zhejiang, one of the most developed coastal provinces. It has a strong industrial base with a large number of SOEs and, in recent years, has attracted an increasing number of domestic private enterprises (DPEs) and foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs). The next two locations are Wuhan and Haerbin, which are old industrial regions that are now undergoing substantial transformation. Wuhan is located in central China, the capital of Hubei province and has many SOEs. Due to the reform of SOEs that started in the 1990s, however, many workers were laid off and that allowed a number of DPEs to develop as an alternative for local employment and economic development. Haerbin is located in the northeast of China and is the capital of Heilongjiang province. The financial burden of its old SOEs has impeded reform in this region. In fact, SOEs still occupy a large proportion of the local economy with relatively little involvement of FIEs. The last two locations, Kunming and Lanzhou, represent less developed regions with lower levels of economic development and individual wealth. The traditional sectors of SOEs occupy a large proportion of the local economy, though with an increasing influence of DPEs. However, FIEs are less significant. These cities are less open and closer to the traditional centralized systems than are the other cities.

Table 1.1 provides a more detailed indication of the nature of the economy of the six cities. Beijing and Hangzhou had a higher level of labour force participation, higher disposable income per capita and higher GDP and GDP per capita than the other cities. Wuhan and Haerbin were both below these cities on these indicators but ahead of Kunming and Lanzhou, which were the poorest cities. Traditional industrial cities such as Wuhan, Hangzhou and Haerbin had a relatively higher level of unemployment than the others. Ownership of the economy also differed between the cities: Beijing and Hangzhou were more open to foreign investment and the proportion of FIEs was higher than in the other cities. On the other hand, DPEs were more prominent in Hangzhou and Wuhan, due to the promotion of the domestic private sectors in these cities. The less open cities such as Haerbin, Kunming and Lanzhou, as mentioned earlier, had a relatively high proportion of SOEs. Finally, in the traditional industrial cities, secondary industry accounted for a large proportion of GDP, whereas Beijing’s economy was oriented towards the tertiary sector.

Within each location we chose two industries: textiles, clothing and footwear (TCF) and electronics. These are both large and important industries in China. In 2007, the TCF sector produced a total output of RMB 2,633 billion (7 per cent of total industrial output) and exported RMB 714 billion of goods (10 per cent of the nation’s exports); it employed 10.4 million workers, 13 per cent of all industrial employees. The sector has been particularly important in generating employment in China, especially for semi-skilled and unskilled workers and for migrants to the cities. The electronics sector produced 23 per cent of national industrial output (RMB 9,180 billion), of which RMB 751 billion was exported; at 6 million, employment was 8 per cent of total industrial employment (China Statistical Press 2008a). Both industries have experienced systematic change since the beginning of the economic reform and, in particular, after China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, as the revaluation of the RMB and increasing price competition forced improvements to technology and management. Within each location we selected six enterprises (eight in Kunming) drawn from a cross-section of ownership forms (SOEs, DPEs, FIEs and collectively owned enterprises (COEs) and enterprise size (small–medium and large enterprises).

Table 1.1 The profile of the six case study cities, 2004–05 financial year

To allow us to investigate the wide range of issues that have been raised by the existing literature and to represent the variety of Chinese enterprises, we developed separate interview questionnaires for managers and for workers. The questions were underpinned by the literature and had particular relevance for both the Chinese management systems we were investigating as well as for the theoretical underpinnings of the research project. Given the key issues being investigated in this book and the analytical framework illustrated in Figure 1.1, three groups of key variables were defined for the analysis. The first group of variables included enterprise-related factors, such as ownership, location, industry sectors (TCF and electronics), size, market orientation, and level of competition. The second group of variables reflected worker-related factors, such as age, gender, and household registration status (hukou, local or migrant workers). The third group of variables included outcome-related factors such as management change, enterprise performance, workers’ satisfaction, and workers’ expectation and hopes for the future.

In conducting the field research we worked with the China Industrial Relations Institute in Beijing (the Institute). In particular, we assigned the Institute the tasks of selecting appropriate enterprises within the guidelines specified above, pilot testing the interview schedules, and conducting the interviews with managers and employees. The employees’ interview schedule contained 95 questions, often with multiple sub-questions; the managers’ schedule contained 84 questions. The interviews were conducted in the enterprise, with each interview taking between 1 and 1.5 hours to complete. To allow for cross-checking of responses from employees and managers the two sets of questions contained some common elements. All completed interviews, from managers and workers, were coded by one of the authors.

Design and structure of the book

This book contains eight chapters. The logic and conceptual rationale of these chapters are arranged in terms of the analytical framework presented in Figure 1.1. Chapter 2 provides a general contextual background covering the evolution of economic reform and the changing economic policies at the macro level as well as the changing enterprise management systems and practices. The chapter commences with a review of the reform path from the early years of restructuring to the later stages that involved the adoption of the so-called ‘socialist market economy’. The characteristics of each stage are identified along with the underpinning ideology and economic thinking. The chapter then shifts to microeconomic reform and the impact of this reform on management systems. This is then followed by a general overview of the impact of this economic reform and changing management systems on workers. The chapter concludes that the reform processes have both top-down and bottom-up characteristics: initiatives from both government and enterprise have proved equally important for the continuation of reform agenda. The debates about ‘socialism’ versus ‘capitalism’ regarding ‘planned’ and ‘market’ economies have shifted from time to time in order to provide a green light for the continuation of the reform. Microeconomic reform has the potential to have a significant impact on management systems through the adoption of new management initiatives, the introduction of new HRM systems, and the way workers relate to management. Nevertheless, Chinese workers are not a homogeneous group, but have a variety of characteristics and entitlements. Therefore, the impacts of reform and management change on workers can be very different.

Chapters 3 and 4 move the discussion to the enterprise level by providing the context with which we will explore the key issues of the impact of reform on enterprise performance (Chapter 5), quality of working life (Chapter 6) and households and livelihoods (Chapter 7). Chapter 3 illustrates the key aspects of HRM among the case enterprises, including recruitment and selection, training and career development, performance appraisal, promotion, employee participation and voice, and employment reduction. In addition, key elements of employment relations (ER) are also discussed, including individual and collective labour contracts, wages and hours of work. The evidence demonstrates that the present state of HRM and ER is in transition towards a more market-based system and away from the socialist policy of lifetime work and protection. This has been partly driven by the impact of economic reform with focus on efficiency and performance.

Chapter 4 analyses the transformation of the ER system at the enterprise level by focusing on the role and activities of trade unions. The evidence shows that unions were numerically strong in terms of presence and membership in the case study enterprises. Perceptions of the role of unions were quite similar between management and employees with the understanding that their key role appears to revolve around the settlement of disputes and handling grievances. However, a reluctance to embrace new roles concerning the representation of workers and the determination of the terms and conditions of work means that Chinese trade unions still remain largely an instrument of the state and management.

Chapter 5 addresses the questions of whether and how what we term intangible management practices (management structure, mechanisms and systems, and organizational culture) affect enterprise performance and employees’ satisfaction. By referring to the theoretical and empirical literature in this area, and analysing the case study enterprises, the evidence confirms that the performance of Chinese enterprises is due to similar kinds of intangible management variables, employee satisfaction and contextual variables that appear to drive the performance of Western enterprises.

Chapter 6 examines the question of the impact of reform on the quality of working life in Chinese enterprises. In particular it explo...