eBook - ePub

Postwar British Politics

Peter Kerr

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Postwar British Politics

Peter Kerr

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers a fresh view of postwar British politics, very much at odds to the dominant view in contemporary scholarship. The author argues that postwar British politics, up to and including the Blair Government, can be largely characterised in terms of continuity and a gradual evolution from a period of conflict over the primary aims of government strategy to one of recent relative consensus. This book provides a provocative and challenging account of the historical background to the election of the Blair Government and will be of interest to a wide audience.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Postwar British Politics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Postwar British Politics by Peter Kerr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction: what's the story?

The established narrative of the postwar period

Introduction

When we approach the study of the past half century of British politics, we are invariably drawn into a narrative which is both straightforward and pervasive. The story which is told is one in which two principal protagonists, the Labour government of 1945 and the Conservative governments under Mrs Thatcher, succeeded in their respective attempts radically to reconstruct the nature of the British state. Between these two periods, British politics is said to have been dominated by a long period of consensus and relative stasis during which government policy exhibited an overall degree of continuity.

The aim of this book is to take issue with the established narrative of the transformation of the postwar British state, and to offer in its place an alternative storyline. This is no small task, for, as we shall see, the assumptions which underpin the conventional story lie deeply embedded in the folklore of British political studies. Therefore, if we are to suggest that the established narrative does not offer an accurate reading of the evolution of the state in the postwar period, then we need to seek reasons as to why so many political scientists continue to reproduce it. Thus, throughout the book, I will engage not only with the established narrative of the period, but also with the methods and motivations of the storytellers themselves. The thrust of the argument which I will present is that political scientists and historians have largely misinterpreted the postwar period due to their normative desire to portray the Thatcher governments as radical and their proclivity to take the rhetoric of government actors at face value.

The purpose of this introductory chapter is to review very briefly some of the general themes of the overall book, outlining the main tenets of the established narrative before highlighting some of the weaknesses in the literature which will be discussed in later chapters. Specifically, I will highlight four broad problems within the literature:

- Most studies of the postwar period provide us with a blend of empirical evidence which is most often contradictory and complex. However, this complexity is rarely reflected in the overall simple storyline which is presented to us. As a result, while we can point to a number of objections to the established narrative within the literature as a whole, these have done very little to overcome the fact that one overarching storyline has tended to prevail.

- Much of the literature is the product of theoretical and conceptual hindsight. In this sense, our understanding of the transformation of the postwar British state has been shaped to a large extent by the experience of the Thatcher years. The perceived radicalism of the Thatcher administrations has served to obscure our perceptions of the comparisons which can be made between the pre- and post-1979 eras.

- The institutionally-directed focus of the discipline has tended to guide our focus towards visible influences on policy-making. This has led to a circumscribed definition of politics and power while generating a tendency to exaggerate the impact of governmental actors upon the structures of the state.

- The discipline suffers from the lack of an authentic notion of social and political change. This has meant that the established narrative of the postwar period has come to be dominated by a series of static representations which fail to provide a sophisticated understanding of the processes and mechanisms which have generated the evolution of the state.

Overall, I aim to demonstrate that these problems have translated themselves into a pervasive misrepresentation of the postwar period and that we cannot understand how this has happened unless we come to terms with the subjective impulses which have generated the narrative of the period. In this sense, it is important to emphasise that the conventional storyline is not an innocent one. Rather, it must be viewed as a chronicle of events which largely reflects the normative assumptions of its authors as well as the rhetorical pretensions of government actors.

The established narrative: a parody of the period?

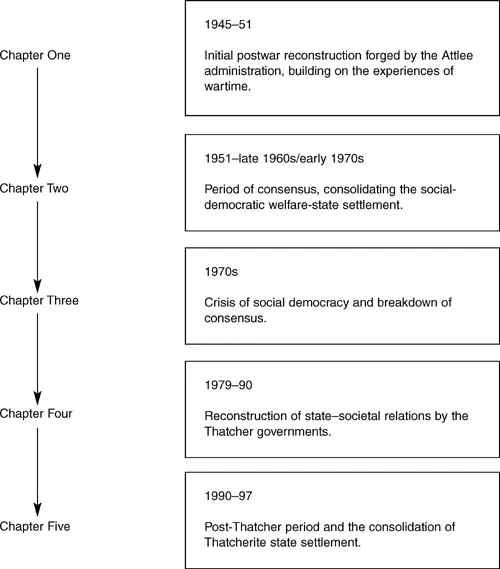

The conventional storyline of the period 1945–97 centres around the respective success of the Attlee and Thatcher governments in reconstructing Britain's political landscape. Essentially, the tale of the transformation of the British state is usually narrated as five main ‘chapters’ (see Figure 1.1). In the first of these chapters, the Attlee administration, building on the experience of wartime, is said to have successfully forged a transformation of state–societal relations around a Keynesian, social-democratic agenda. In the next, this reconstruction is consolidated during a sustained period of policy consensus and state settlement. In Chapter Three, the consensus begins to crack amid a period of political instability and economic uncertainty. Thatcherism thus makes a grand entrance in Chapter Four, with a series of neo-liberal reforms which sweep aside the earlier state settlement, while John Major dithers into the last of these chapters to provide a further period of consolidation and settlement. The villain in this piece inevitably varies, depending on whether we are supporters of either social democracy or the free market. The hero throughout, though, appears to be the British political system, which reveals its essentially dynamic qualities and proves itself to be contingent upon the articulation of successfully constructed state strategies.

Some may object that this account presents a mere parody of a story

Figure 1.1 The conventional story of postwar reconstruction

which contains far more twists and sub-plots than is being acknowledged here. Others may object to the assertion that this narrative is as pervasive as the previous paragraph suggests. After all, three of the four chapters in the story have been subject to a large degree of both debate and revision.1 For example, political and economic historians have recently begun to dispute the extent of change under both the wartime administration and the subsequent Attlee governments (see for example: Bartlett 1977; Barnett 1986, 1996; Tiratsoo 1991a; Mercer, Rollings and Tomlinson 1992; Fyrth 1993; Tiratsoo and Tomlinson 1993; Johnston 1999).2 In a similar vein, many such authors have also begun to challenge the extent of both the wartime and postwar consensus (see for example: Pimlott 1988, 1989; Jefferys 1991; Brooke 1992; Rollings 1994; Marlow 1996, 1997; Kerr 1999). Likewise, the radical credentials of the Thatcher governments have also been open to a more modest, but no less significant, degree of scepticism (Jessop et al. 1988; Riddell 1991; Marsh and Rhodes 1992, 1995). The problem, however, is that these qualifications to each of the individual chapters of the conventional story have done little to dent the overall tale of the transition from a consensual, social-democratic state settlement to Thatcherism. As a result, they remain only as footnotes to the original story, for, as Chapter Two of this book will demonstrate, the prevailing view amongst political scientists, state theorists and historians alike, is that the Thatcher governments succeeded in reconstructing a political landscape which was preconstituted by earlier postwar administrations and which was radically different from the one which they subsequently bequeathed to the Major government. In this sense, the Thatcher governments have overwhelmingly been portrayed as having entered and reshaped a political terrain which had been previously mapped out by the Butskellite policy consensus. On the economic front, their strategy is assumed to have been a response to the prior failure of Keynesian and interventionist attempts at reversing Britain's long-term structural decline. At a cultural level, the Thatcherite cocktail of neo-liberalism and traditional Conservatism has been read as a reaction against the social-democratic ideals conveyed by earlier postwar political actors. In these ways, the idea that the Conservative governments after 1979 represented a fundamental and near absolute departure from previous practice has been held firmly intact.

Clearly then, the literature needs to be unpacked. As a result, the opening two chapters of this book will review the literature on both the Thatcher period and the earlier era of consensus respectively. As we shall see, most studies of these periods provide us with a contradictory blend of evidence. On the one hand, we are faced with the overriding assumption that the British state has undergone two significant and fundamental transformations since 1945. On the other hand, however, we are given many reasons to assume that the state has in fact exhibited more consistency and continuity than is generally acknowledged. This latter view is particularly prevalent within the literature on Britain's long-term economic decline, which most authors attribute to the overall lack of fundamental reform to Britain's political and institutional architecture. Yet, despite these contradictory appraisals (which are often given by the same authors), we are invariably confronted with only one overarching interpretation. It appears not to matter to the presentation of the overall story therefore that: ‘few people now have any belief in the revolutionary intent or impact of the 1945–51 Labour governments’(Mercer, Rollings and Tomlinson 1992), or that there is an increasing awareness that the consensus ‘is an illusion that rapidly fades the closer one gets to it’ (Pimlott 1988). Likewise, the persistent claim that many continuities exist between Thatcherism and the earlier postwar period, appears to have been similarly unheeded. For the overwhelming assumption which pervades the literature on the period is that the Thatcher governments were successful in radically altering a state settlement which had been transformed by the impact of a social-democratic consensus.

In the following sections, and in the chapters which follow, I will argue that the established narrative of the postwar period presents a storyline which is overly stylised and ultimately misleading. Yet it is alluring because it serves the pejorative assumptions of both the left and right. As a result, the real parody of the period lies, not in the way the overall story has just been presented, but in the manner in which political scientists, historians and state theorists alike have oversimplified and related the complex series of events that have occurred in British politics since the end of the Second World War.

Narrating the period: insight or hindsight?

One of the most conspicuous features of the established narrative is the striking similarity which it bears to Mrs Thatcher's own interpretation of events (see Thatcher 1993: 3–15). We should consider this important, for, as Brendan Porter (1994: 249) points out: ‘what we found confronting us in May 1979 was a Prime Minister with a very pronounced sense of history’. Here, it is crucial that we remain sensitive to the fact that Mrs Thatcher ‘interfered shamelessly with our subject, telling us what we should think about a whole range of historical issues’ (ibid.: 246).

One major reason why this should concern us becomes clear when we start to view the debate over Thatcherism. The earliest attempts at theorising the significance of Thatcherism pointed to the Conservative governments' ambitions of achieving a new type of political and ideological hegemony. In a neo-Gramscian sense, this ‘hegemonic project’ entailed capturing the hearts and minds of the electorate in order to promote new sets of ‘common-sense’ assumptions about the nature of political activity. Thus, Thatcherism was, from its inception, regarded by some authors as a potentially ‘manipulative’ project, designed to alter existing perceptions of political realities. Yet, as we shall see in Chapter Two, for the authors who proposed such ideas, very little reflexivity was paid to the way in which Thatcherite perceptions of postwar British politics could filter into their own analyses of the period. In this sense, most authors neglect any real consideration of the fact that Thatcherite common sense was built upon a set of ideological assumptions, not only about the nature of Thatcherism itself, but also about the historical context in which Thatcherism emerged. The result has been an outpouring of analyses which passively submit to Thatcherism's self-proclaimed radicalism and its narrow interpretation of postwar British history. It is arguable that an important element of Thatcherism's attempt to create its own common sense has been the willingness of political scientists and historians to bolster some of the core assumptions around which the Thatcher project was constructed.

As far as the Thatcherite view of history is concerned, the pinnacle of Britain's grandeur is to be found in the halcyon period of the Victorian Age. Here, the true spirit of British entrepreneurialism was believed to have been released amid a flourish of unbridled capitalist development. From there on in however, the story of the past hundred years or so of British history has been one of inexorable decline caused by the deleterious effects of creeping socialism. After 1945 this decline is perceived to have grown apace as the Attlee administration pushed the accelerator towards a more ‘centralising, managerial, bureaucratic, interventionist style of government’ (Thatcher 1993: 6). For her own part in this story, Mrs Thatcher cast herself as a modern-day Moses, endowed with a popular mandate to part the Red Sea of socialism, and deliver her nation to a promised land flowing with non state-sponsored milk and plastic money. Hand in hand with such prophecies went the self-fostered image that the Thatcherite staff of conviction would be waved against the evils of consensus.

In this sense then, Thatcherism was able to claim that it was presenting something new to the British political scene. Having illustrated the story of Britain's century of decline with a swathe of red brushwork, Mrs Thatcher and her followers could legitimately point to her own brand of Victorian values and economic liberalism as a distinctive response to Britain's decline. What should concern us here is the extent to which writers from both sides of the political spectrum have clamoured to avow the Thatcherites' self-proclaimed radicalism. The arrival of the Thatcher governments onto the political scene drew the attention of political scientists more than any other period in the postwar era. This point has been made by Marsh and Rhodes (1992: 1), who claim that: ‘Margaret Thatcher's effect on British politics, or at least on British political scientists is clear; the study of Thatcherism became an academic and journalistic industry’. Inevitably, much of this literature was inspired by the apparent distinctiveness, in both style and substance, which the Thatcherites brought to bear upon the policy-making arena. According to Kavanagh (1987: 288) for example: ‘in terms of policy style and policies, there is something new and radical about the Conservative Party under Mrs Thatcher’. These types of unequivocal, and most often unqualified, statements are to be found scattered throughout the literature. One of the key aims of this book is to demonstrate that in casting a British government, which was wedded to the idea of limited state intervention and a traditionally monetary ethos, as a ‘new’ and ‘radical’ departure, politicians historians and political scientists have been equally involved in myth-making of significant proportions.

The charge being made here is that academics have been guilty of reproducing a narrative which concedes too readily to the rhetorical machinations of the Thatcher governments. This is not to suggest that Mrs Thatcher successfully engineered her own postwar history. However, it is important to emphasise that the vast majority of interpretative accounts of the period have been written in the context of the Thatcher years.3 This point has been made by Catterall, who observes that:

interest in the postwar era has been stimulated in recent years by the apparent challenge to the postwar consensus mounted by the Thatcher government…. In the process, the break it has supposedly made with the past has stimulated increasing interest in themes such as the postwar consensus or the practice of Cabinet government.

(Catterall 1989: 221–2)

This eagerness to assess the impact of Thatcherism has led many authors to subscribe passively to a narrative which accords very favourably with the Thatcherite view of the earlier part of the postwar era. Of course, there are inevitable areas of dispute, particularly over the extent to which social-democratic interventions played a role in inhibiting British economic development. Yet despite this, the overall tale of Thatcherism railing radically against an earlier interventionist and collectivist state settlement remains intact, and as yet relatively unquestioned.

Consequently, when we come to view the transformation of the postwar British state, it is important to question the extent to which our understanding of the period has been the result of conceptual hindsight rather than true academic insight. While I do not make the claim that it is possible to escape the inevitable trap of reading history backwards, it is nevertheless important to retain a certain reflexivity about the dangers which it imposes. As I shall discuss in Chapter Three, this caveat is particularly relevant to our understanding of the postwar consensus thesis. The twin notions of ‘Thatcherism’ and ‘consensus’ gained an almost mutual ascendancy towards the end of the 1970s. What is significant here is the way in which the idea of consensus has been utilised by various authors in order to serve broader assumptions about both the Thatcher era and the earlier postwar period. As Rollings (1994: 184) points out, much of the debate over conse...