eBook - ePub

Managing Buyer-Supplier Relations

The Winning Edge Through Specification Management

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Managing suppliers is a complex process that is often underestimated. This book presents research carried out by a practising manager in the automotive industry, coupled with over six hundred interviews with representatives from the automotive, aircraft and white goods industries, in order to describe the tools and techniques needed to better manag

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing Buyer-Supplier Relations by Rajesh Nellore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 A theoretical perspective on specifications

Today firms are more actively involving suppliers in their integrated development processes and have identified suppliers as a source of competitive advantage (Cusumano and Takeishi, 1991; Nishiguchi and Beaudet, 1998; Quinn and Hilmer, 1994; Richardson, 1993). That means that there is room for development and identification of factors that could help sustain or improve the relationship between the buyer and the supplier in outsourced product development. There are various factors that one could look into when trying to improve or sustain the buyer–supplier relation such as Just In Time, location of suppliers, trust, specialised investments, specifications and contracts (Cusumano and Takeishi, 1991; Harris et al., 1998; Lamming, 1993; Sako, 1992). With the exception of specifications, the literature dealing with buyer–supplier relationships is very rich. Supported by few existing references (Smith and Reinartsen, 1991; Kaulio, 1996; Harris et al., 1998), this book sets out to explore the role of specifications in product development.

Setting the scene

In order to grasp the essence of specifications, one must go back in time to the era of craftsmanship and observe the changing role of specifications in the automotive industry, as it was the first to be hit by the ‘Japanisation’ of industries. We will first discuss the evolution of work practices from craftsmanship to lean production, then study the varying demands on the services of the suppliers in the work practices discussed above, and finally analyse the changing role of specifications in these eras.

Evolution of the automotive industry and the changing role of suppliers

In the era of craftsmanship there was a direct link between the customer and the shop floor personnel. A classic example of an automotive firm from the craftsman-ship era is P&L–Panhard & Levassor (Womack et al., 1990) which was the leading automotive company in 1894. There were no car dealers and no standards in the late 1800s. Each car was tailored to individual customers. Since there was no standardisation, there was a need for rework such as filing and shaping parts so as to make them fit. There were a number of individual sub-contractors working directly in the P&L plant (ibid.). There were obvious problems with the crafts-manship style due to the following reasons:

- high production costs;

- reliability problems as no two cars were alike;

- inability on the part of the independent sub-contractors to innovate.

The problems inherent to the craftsmanship era (in automobiles) gave rise to mass production. In the beginning of mass production ‘Fordism’ was developed by Henry Ford (manufacturer of the Model T car). Ford started by using standard gauges, and thus standardising the work procedures so that the components could be interchangeable (Womack et al., 1990). Ford also pulled everything in-house, manufacturing everything that was required to make an automobile under one roof. The parts were standard and, thus, did not require skilled personnel, unlike during the craftsmanship era. During the 1950s, Ford outsourced components that were previously made in-house. The outsourcing was price-based and the supplier with the lowest quote got the orders. Low profit margins meant that the suppliers could not invest in research and development and thus innovate for the customer. The pioneer continuous flow system developed by Ford–steel and rubber came into the factory and ready-to-drive cars came out (Krafcik, 1988)–had to be complemented by a number of managerial principles before it was possible to set up a traditional model of mass production. Though Ford was successful, he did not provide the customers with variety. However, Alfred P. Sloan of General Motors did.

Womack et al. (1990) and Berggren (1992) emphasise the importance of the development at General Motors during the 1920s under Alfred Sloan. Sloan provided variety to the customer and also created independent profit centres within the General Motors group to make components. Sloan developed stable sources for outside funding, created new professions within marketing and finance to complement the engineering professions, etc. In the 1980s, General Motors tried to outsource many components that were made by the in-house profit centres, but since this was met with internal resistance, the outsourcing percentage remained quite small and was still price-based. Sloan’s ideas combined with Ford’s manufacturing system (technology) and Taylor’s scientific management (organisation) were instrumental in developing the traditional mass production system (Berggren, 1992).

Over time, each firm goes through significant changes in its strategy, experiences deep crises and/or strong growth, and changes in its geographical penetration (market and manufacturing investments in new regions, or withdrawals) (Boyer and Freyssenet, 1995). The specific trajectory of Japanese manufacturing and, in particular, Toyota, gave rise to the lean production system. Krafcik (1988) was the first to coin the name ‘lean production’. In the lean production paradigm, independent suppliers are involved to a large extent and the OEM is restricted to vital systems or the whole product, in this case, the car (Lamming, 1993). Large numbers of components and systems may be outsourced according to the lean production paradigm. Womack and Jones summarise the main elements of the lean enterprise as follows:

- focusing on a limited number of activities within each firm;

- strong collaborative ties with clear agreements on target costing;

- joint definition on levels of process performance;

- joint definition on rate of continuous improvement and cost reduction;

- consistent accounting systems;

- a well-defined formula for splitting the losses and gains. In the lean enterprise, each participant adds value to the production chain;

- reduction of waste that gives the potential for significant performance improvement;

- rotation of middle and senior managers between company operations; suppliers and foreign operations are the central elements of this new industrial structure. (Womack and Jones, 1994)

It will be observed from the above that the role of the supplier has changed. In the craftsmanship era, the role of the supplier was to take charge of making parts and components that were fitted together by the main assembler. Sloan provided variety for the customer in the mass production era and set up independent profit centres within the General Motors group, though once again there was limited outsourcing that was price-based. In the era of lean production, the supplier involvement shot up from no or little involvement to increased involvement and responsibility.1 Suppliers are now responsible for entire systems and subsystems. In the current era of lean production, supplier management is considered to be very important and many manufacturers are concentrating on their core competencies, leaving the rest to the suppliers (Leenders et al., 1994).

Evolution of the role of specifications

We saw that the role of the supplier has changed from the craftsmanship era to the lean production era. The changing roles of suppliers have obvious implications for the specifications because the more involved the suppliers are, in terms of time and complexity of the systems, the more they will presumably be involved in the specifications.

The specifications in the case of craftsmanship were very loose as the goods arriving at P&L were described as having ‘approximate specifications’2 (Womack et al., 1990). General Motors had well-defined specifications,3 as otherwise it would have been hard to estimate the lowest cost during the bidding process for the part in question. In cases where the specifications were not well defined, General Motors suffered losses4 as the suppliers could exploit them, i.e., by charging money for changes in specifications. In lean production, since supplier involvement is probably the highest as compared to all the other eras, the specifications would require joint involvement. Hence, the role of specifications has been changing from a loose specification in the craftsmanship era, to a tight specification, and finally to a joint specification (where both the OEM and the suppliers collaborate in the writing of the specification). There can be problems with each and this was quite evident considering the losses in the craftsmanship era and the mass production era (ibid.).

Understanding specifications

In the product development process there are various activities that take place between the buyer and supplier, for example, joint testing, computer-assisted design (CAD) data exchange, joint operational design, etc. Specifications are also exchanged between the buyer and the supplier. Specifications have been defined in a number of different ways. In order to understand the actual term specifications, the term design needs to be explained. Vincenti (1990) describes the term design5 and takes it to mean two things, namely, the contents of a set of plans and the process by which these plans are produced. A set of plans for the product is equivalent to the written description of products (Smith and Reinartsen, 1991) and may be seen as a narrow definition of specification. Specification could also correspond to the process of producing the plans (Kaulio, 1996). This may be seen as a broad definition of specification. In other words, the broad definition of specifications not only includes the process of arriving at the specification, but also encompasses the document called the specification (ibid.).

Specifications could also be seen as representing two different perspectives, namely the commissioning perspective and the mediating perspective (Kaulio, 1996).6 In the commissioning perspective, there is one-way communication and the contents of the specifications are essentially ready and simply have to be worked on. In the mediating perspective, the specification is a forum for dialogue and, thus, the specification is created by the joint effort of the different actors in the development process. Kaulio further comments that the commissioning perspective corresponds to the narrow definition of specifications, while the mediating perspective corresponds to the broad definition of specifications.

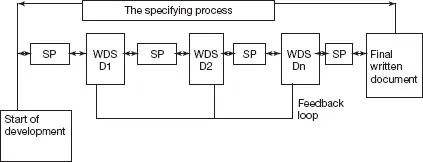

It is difficult to comment on which is superior: the narrow definition or the broad definition. Even in the narrow definition, the process is present because without the process there will be no specification. Essentially this discussion indicates that there are two processes involved. The first is the process of getting to a final specification document, and the next is to execute the contents of the specification document and to realise the product. For the purposes of this book the following definitions of specification (Figure 1.1) will be used. The specifying process is defined as the process involved in getting to the final written document. This is done by creating and repeating a number of draft documents (through sub-processes).

The specifications are a means of conducting dialogue in the development process between both internal and external actors. They assist in the coordination and integration of the design activities (Kaulio, 1996). The creation of interdependent tasks linked to each other and performed by specialised participants brings a need for co-ordination (Karlson, 1994). If the specifications were falsely interpreted by the supplier or the buyer due to a faulty process, the output would be chaotic. This means that the specifications may have to consider both the internal process of the supplier/buyer as well as the external process (the patterns of specification interaction between the buyer and the supplier). Imai et al. (1985) comment that information is a key resource and is of utmost importance in the new product development process. In outsourced product development, the buyer and the supplier each deal with a separate part of the environment and these tasks need to be linked to each other (Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967), thereby necessitating a high degree of co-ordination between the buyer and the supplier and thus in the information flow. This means that the flow of information between and within processes is very crucial for the success of the product development process and is a vital component for the survival of the product development process as a whole. In other words, no information flow would mean no co-ordination and thus the new product development process would be affected.

Figure 1.1 The view of specifications

Notes: SP = Specification Sub-Process (continuous development of the specification documents)

WDS = Written document called the specification

D1 = Draft 1, D2 = Draft 2, Dn = nth draft of the specification document

This move towards increased supplier involvement requires both internal and external co-ordination between and within the OEM and supplier firms. This is because organisations, due to external contingencies, become segmented into units, each of which is given a special task of dealing with a specific part (ibid.). This means that the buyer and suppliers engage in specialised tasks and these have somehow to be linked together. These tasks are interrelated and interdependent and cannot be performed in isolation. This division of labour and the interdependence between the tasks that are carried out by the OEM firm and the suppliers make the need for co-ordination all the more important (Karlson, 1994).

Many analysts fail to recognise the importance of co-ordination which results in problems when making the product (Karlson, 1994). Simon (1976) sees organisations as ‘decision making and information processing systems’, which, according Start of development to Karlson (1994), moves the focus from how people are grouped to the decision process itself. Galbraith (1973) subscribes to the idea of co-ordination being a decision process.7 The greater the uncertainty,8 the more information that will need to be processed (ibid.). Simon9 (1976) argues that co-ordination is a process consisting of three steps, namely, the development of a plan of behaviour for the members of the group, the communication of that plan to the members, and finally, the acceptance of the plan by all the members. This indicates that the co-ordination of the specific activities and competencies (suppliers focus on parts/components while the OEM focuses on the overall architecture) is essentially a decision process in which transformation of communication and information is important. This focus on communication by both Galbraith (1973), and Simon (1976) could mean that if more emphasis is put on communications (quality, amount, time, etc.), co-ordination would be more positive.

Solutions to the problems of communication include putting specialist groups together in the same location, providing them with tools to communicate, etc. (Karlson, 1994). Karlson suggests that the interdependency between the tasks requires co-ordination to be performed on an ongoing basis. Co-ordination could be facilitated by procedures, plans, standardised product structures, the organisational members themselves, etc. According to Galbraith (1973), the organisation can handle task uncertainty in two major ways, namely, by reducing the need for information processing (creation of slack resources and self-contained tasks) and, second, increasing the capacity to process information (investment in vertical information systems and creation of lateral relations). These elements are as follows:

- Slack resources–Uncertainty is reduced by increasing the amount of slack, for example, having tolerances, increasing the lead time to delivery, etc., though this will be at a cost to the customer. The specifications10 allow the creation of slack as the development personnel could make the different trade-offs with respect to the whole product, described by the specification.

- Self-contained tasks–Having a number of skills pooled together in a group reduces uncertainty. This reduces the diversity faced by the group and facilitates the collection of all the resources required to solve a problem. The specifications may be worked on by the different groups in charge of the different areas of the final product. The specifications thus facilitate the creation of self-contained tasks.

- V...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Tilte

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. A theoretical perspective on specifications

- 2. Specifications: do we really understand them?

- 3. Visionary-driven outsourced development

- 4. Redefining the role of product specifications

- 5. Mapping the flow of specifications

- 6. Applications of specifications in outsourcing: building on Quinn and Hilmer

- 7. Applications of specifications in outsourcing: portfolio approaches

- 8. Contracts to help validate specifications

- 9. Managing systems suppliers: an uphill task

- 10. Digital procurement

- Bibliography

- Index