![]()

1

Transformations in the primary life cycle: the origins and nature of China’s sexual revolution

Pan Suiming

Introduction

This chapter discusses the origins and nature of China’s sexual revolution with reference to the results of a nationwide survey on sexual behaviours and relationships in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which was conducted by the Institute for Research on Sexuality and Gender at the Renmin (People’s) University in Beijing between August 1999 and August 2000 (Pan et al. 2004). The survey involved 36 investigators and was supported by the Social Science Fund of China; the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, USA; the Population Research Center NORC, University of Chicago, USA; and the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, University of North Carolina, USA. During the course of this survey, we interviewed 3,824 subjects from urban and rural China, including members of the transient labour force who have left their original places of residence (usually rural) to find work in other parts of China (usually urban). Survey results were obtained using procedures adopted in the PRC’s National Census. Seventy-six per cent of the 3,824 interviewees responded.

The survey constitutes the most comprehensive study of sexual behaviours and relationships in the PRC to date (for earlier discussions, see Jiang 1995; Li 1999; Liu 1992). Apart from using standard social survey methods, we deployed three innovative strategies. First, we interviewed survey participants at a hotel, usually outside of their normal work hours, rather than interviewing them in their place of residence. Subjects are unlikely to discuss their sexual conduct with investigators in their own home, particularly when their family members are present. We therefore invited subjects to our hotel and conducted the survey on a one-to-one basis, with the investigator being of the same gender as the interviewee. Second, in order to obtain a greater degree of anonymity, the investigator who organized these meetings was different from the investigator who conducted the interview. Third, we conducted the survey using a laptop computer. As demonstrated in the ‘1998 USA Male Adolescent Survey’, ‘computer assisted surveys’ elicit more sensitive data than the ‘fill-in-the-questionnaire’ method (Turner et al. 1998). Using this method, questions appear on the computer screen in a consecutive manner, with the survey participant using the computer keyboard to select the desired response. Investigators showed participants how to use the computer by first answering non-sensitive data. Once the sensitive questions on ‘sex’ appeared, the survey participant took over control of the computer and the investigator moved out of view of the computer screen.

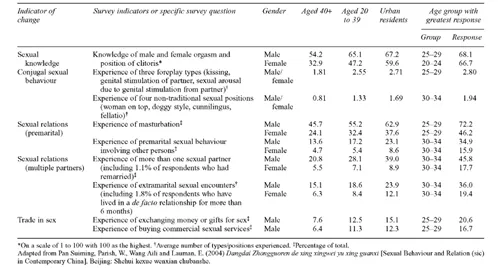

The results of this survey suggest that a sexual revolution, rather than a gradual evolution in sexual behaviours and relationships, is taking place in present-day China. To highlight the existence of a sexual revolution in China, I have tabulated the survey responses in accordance with the five major indicators of changes in the nature of sexuality, as noted by Western scholarship (Reiss 1990:85–7). These indicators are: (1) the extent of openness or public knowledge of sex; (2) the nature of sexual conduct; (3) the nature of sexual relationships; (4) the sexuality of women; and (5) the status of sex in mainstream society. While scholars concur that these five indicators can be used to measure changes in the nature of sexuality, there is considerable disagreement as to exactly how, and in what way, they combine to constitute a sexual revolution. One evident problem here is that both knowledge of and types of sexual activity have a close correlation with age. Members of the younger generation in China today, for example, are likely to be more sexually active than members of the older generation. Hence it is difficult to ascertain if a ‘revolution’ has taken place simply by comparing the sexual activities of younger and older people at a fixed point in time. To overcome this problem, survey participants were requested to record all of their sexual experiences to date, i.e. we measured the ‘accumulation’ of individual sexual experiences over the course of a life. Using this method, it is possible to compare the sexual activity of younger and older generations. Moreover, it is possible not only to demonstrate that the sexual experiences of members of the younger generation exceeds those of members of the older generation, but also to determine whether or not a shift in sexual behaviours has occurred and to obtain a sense of the extent of that transformation (see Table 1). As Table 1 shows, all the measured indicators of changes in the nature of sexual behaviours and relationships have exhibited dramatic increases over time, except for the rate of female premarital sex. This implies that a sexual revolution is taking place in China today. However, differences within the various indicators – stemming from urban–rural differences, gender differences, and differences in educational level – suggest that this ‘revolution’ is first occurring predominantly in urban areas among relatively young and well-educated males.

If we can conclude that a sexual revolution is currently taking place in present-day China, then how do we go about explaining its origins and nature? When discussing the origins of a sexual revolution, Western scholars often refer to the concept of sexuality, understood as an autonomous entity that can serve a variety of social functions in both an independent and direct fashion (e.g. Reiss 1990; Weeks 1985). But this particular mode of conceptualization is not applicable to an examination of the Chinese case. Sexuality in China cannot be conceptualized as an autonomous entity or something that is individualized in the body of the person because, historically speaking, the regulation of sex in China did not aim to control sexuality directly. Consequently, I argue that sexuality in the context of

Table 1. Changes in sexual experience

China is better understood as one, unremarkable aspect of the ‘primary life cycle’ (chuji shenghuo quan). This concept refers to both the sum of and the relations between the most basic of human activities, such as sex, reproduction, physical sustenance, and the social and sexual interactions between members of the opposite sex.

This chapter first outlines the concept of the primary life cycle and explains its utility for assessing the kinds of transformations that have taken place in the nature of Chinese sexual mores and behaviours since the 1980s. With reference to the survey results, it then demonstrates that the origins of China’s sexual revolution can be traced to five considerations. These are: the increasing separation of sex from reproduction; the challenge posed to traditional conceptions of marriage by the more recent concept of love; the increasing recognition of the significance of sex in marriage; the growing detachment of sexual desire from romantic commitment; and the changed nature of life for women in China today. Following a discussion of each of these considerations in turn, I conclude that China’s sexual revolution is neither a straightforward product of ‘Western influences’, nor even of dramatic changes within the nature of sexuality itself; rather, it stems from the radical changes that have occurred due to the interactions between sex and sexuality and the other component aspects of the primary life cycle.

Conceptualizing sexuality in China: the primary life cycle

Sexuality is a key focus of any Western discussion of a sexual revolution, but there is no accepted translation of the English-language term ‘sexuality’ in modern Chinese, even though the term ‘sex’ (xing) is now quite common. In fact, in ancient China, there was no definite term for the biological notion of sex let alone sexuality. The closest terms were se, which refers to sensuality and carnal pleasure, dunlun, which refers to representations of certain movements, and qing, which refers to passion or sentiment. This lack of precise terminology suggests that, in traditional China, just as ren (person) never referred to the individual, but rather was incorporated into jia (family), so too xing (sex) was never an independent category but rather was submerged within a greater social totality.

In China today, the English-language term ‘sexuality’ has been variously rendered as xing xianxiang (sexual phenomenon), xing zhuangkuang (sexual state), xing jingyan (sexual experience), and xing suzhi (sexual quality). I myself have coined and tried to popularize the use of the term xing cunzai to refer to the English-language understanding of ‘sexuality’ (Sigley and Jeffreys 1999:50–8). This is because I think the term xing cunzai can be used to refer to sex not as a natural category, but rather as something that exists and is understood in terms of existing social frameworks, or as something that refers to the nature of the social organization of sexual behaviours in contemporary China. However, as the previously-mentioned translations imply, the term ‘sexuality’ in Chinese is usually conceived of as an extension of the biological notion of sex and emphasizes manifestations of sex within actual social, cultural, psychological, behavioural, and gendered contexts.

The absence of Western-style conceptions of sexuality in pre-sexual revolution China can be illustrated with reference to the dominant principles and associated methods of regulating sexual behaviours that existed prior to the May Fourth Movement of 1919, a movement which served as the catalyst for an intellectual and, subsequently, social revolution in China. These principles and methods are encapsulated in the following nine regulatory norms: (1) the understanding that reproduction is the primary objective of sex; (2) the gendered principle that women exist for male pleasure; (3) the notion that sex is a marital obligation and duty; (4) the notion that mutual gratitude and appreciation (fuqi en’ai) are more important in regulating sexual relations than romantic love (langman qing’ai); (5) a general objection to ‘seeking pleasure’ as the qualitative measure of sexual activity; (6) the imposition of quantitative restrictions on sexual activity through the understanding that excessive sex causes exhaustion and harm to male health; (7) the existence of social prohibitions on talk of sex, flowing from the notion that people will engage in sex but they should not talk about it; (8) the existence of social controls on sexual behaviours in the form of fear of gossip concerning the real and imagined sexual behaviours of given individuals; and (9) the existence of age restrictions on sexual conduct based on the understanding that minors and the elderly do not engage in any form of sexual activity.

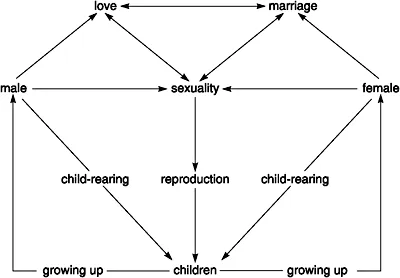

All of these nine regulatory norms refer to sex in relation to marriage, reproduction, health, age, relationships, and so forth, but none of them turns on a clear understanding of sexuality as an independent category. In the context of China, therefore, it is difficult to analyse and assess the nature of the current sexual revolution by presuming that sexuality has an autonomous nature. Instead, China’s sexual revolution is better understood with reference to the concept of the primary life cycle, that is, the totality of the functions and relations between the most fundamental aspects of human activity (see Figure 1).

In the context of China, we can say that adult heterosexual sex differs from other human activities insofar as it tends to involve two members of the opposite sex and is traditionally geared towards reproduction and affirming interpersonal relations. This interaction coalesces to form the mainstream social structure. I refer to this interaction as the primary life cycle because, from the viewpoint of the birth and development of the individual (geti), it constitutes the most basic form of society, and it also constitutes the primary ‘unit’ (danyuan) of the mainstream social structure.

Examined in this static fashion, the concept of the primary life cycle appears to resemble conventional conceptions of the family. However, it differs from traditional understandings of the family in three main ways. First, the family is conventionally understood and examined as a unified structure; it is first examined as a whole and then broken down into its individual components. In contrast, the concept of the primary life cycle encourages us to look at each of the component activities within the ‘cycle’ and then examine how they interact and what kind of network they form. Put another way, the concept of the family is akin to looking at a house and its structure from the outside, whereas the concept of the primary life cycle encourages us to first examine how the basic

materials of a house and its structure are assembled, and then consider what they eventually form.

Second, the concept of the family implies the cohabitation of a number of individuals within a given space, with the individual constituting the most basic structural unit of the family and the various interpersonal relationships between these individuals ...