1 The party elite and China’s

trajectory of change

Andrew G. Walder

Since the political crises of 1989, China’s trajectory of political and economic change has diverged radically from that of virtually all of the states that were governed by similar political regimes at the beginning of that year. Only two such regimes – China and Vietnam – have avoided prolonged recession and have experienced rapid, market-oriented economic growth.1 And these are the only ones in which communist parties have continued to rule with little disruption of past organizational practices. This raises two key questions about China’s future political trajectory. The first is the one that has received the most attention: to what extent has the party’s capacity to govern changed during these years? Are there any signs of the kinds of political decay that led to the collapse of so many regimes after 1989, or has the party elite revitalized itself and strengthened its ties with key sectors of society? The second question is often neglected: mindful of the evolving features of the party, what are the crucial challenges it will face in the coming years, and what kind of role can we expect it to play as an agent of future political change? The longer that China continues along its current trajectory of change, the less relevant are the prior examples of collapse and regime change in Eastern Europe and the USSR. The real question is whether it still makes sense to think of China with reference to these failed states, or whether we should begin to think about it in new ways that reflect how far it has diverged from the old socialist model.

To address these questions, it is important to be clear about how China’s trajectory differs from that of once-comparable regimes. The first is obvious: that China’s party hierarchy survived 1989 and in many respects has been revitalized in the years since. Unlike most post-communist regimes, China’s elites have not been forced from their posts by regime change. Instead, as in Vietnam, they have remained in power to preside over a prolonged process of market reform and heightened participation in the world economy. In China, this process began a decade before the crucial 1989–1991 period, and it has accelerated since.

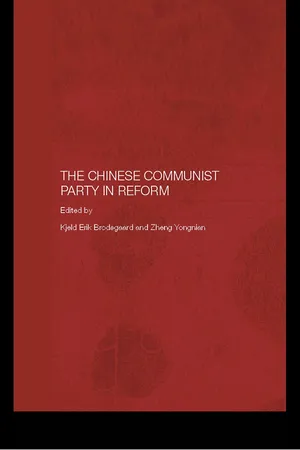

The second difference is also well known. The economies of regimes that collapsed between 1989 and 1991 have fared much more poorly than China’s. Central Europe as a whole has only recently emerged from its long transitional recession, with levels of real GDP still only a few percentage points above 1990 levels. The GDP of the former USSR has experienced a long decline and has yet to recover (Figure 1.1). By far the best performing economy in the region has been that of Poland, whose economy has grown a respectable 44 percent over the decade. However, during the same period the Chinese economy has grown almost three-fold. The sharp contrast between China and these other nations has long fuelled lively discussion about the nature, pace and sequencing of economic reform, but it is hard to avoid the observation that the most important determinant of these diverging paths is beyond the control of policymakers. An abrupt collapse of political institutions and, along with it, an entire system of economic regulation and property ownership was detrimental to the economic health of the nations in the Russian empire. The legacy of this collapse still haunts the polity and economy of Russia and other regimes to this day.

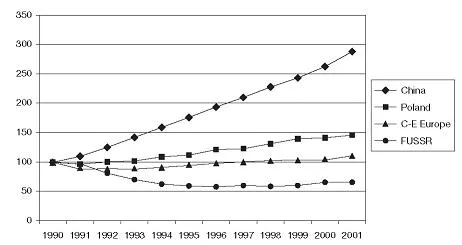

A third striking difference – less widely appreciated – is that China’s economic growth has been accompanied by an unprecedented expansion in college-level education that is rapidly transforming its urban elites (Figure 1.2). A comparable process occurred in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe almost half a century ago, well in advance of the stagnation of their economies and eventual collapse. In China, on the other hand, the massive expansion of college opportunity is occurring in tandem with a rapid economic growth and a level of openness to the outside world that surpasses anything experienced in the histories of other communist regimes. The number of college graduates has grown even more rapidly than China’s economy, and it has sent well over 100,000 graduate students abroad.

Figure 1.1 Growth in real GDP in China, Poland, Central and Eastern Europe, and the former USSR, 1990–2001 (1990 = 100)

Source: World Bank, Transition: The First Ten Years, and Zhongguo tongji nianjian 2002, p. 54.

Figure 1.2 Expansion of college education in China, 1950–2000 (thousands of students)

Source: Zhongguo jiaoyu nianjian, 1981–2001.

A fourth distinctive feature of China’s trajectory is that the privatization of state assets has been delayed and slow, in sharp contrast with most post-communist regimes, which privatized their assets rapidly in their first years of transition. China’s large private sector has come about not via the transfer of state assets to private owners, but through new start-ups outside the state sector and through foreign investment. In most post-communist regimes, the private sector was created much more rapidly, by transferring state assets to new owners. In some regimes – particularly Russia – the process permitted the bulk of public assets to fall into the hands of incumbent managers and former political officials. Even after more than two decades of market reform, the proportion of China’s economy in the private sector lags behind most post-communist regimes (see Table 1.1).

These observations may appear unexceptional, but in comparative perspective they distinguish the fate of China’s political elite sharply from other regimes, which generally fall into four types. The first such type is one typical of Central Europe and the Baltic States. In regimes such as Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Estonia, party organizations collapsed shortly after defeat in early popular elections by political parties that were dominated by people outside the former political system.2 The party’s appointment system collapsed, and its entire hierarchy of party posts was rapidly dismantled. Many of these post-communist regimes were anti-communist in orientation, and purged the government of former officials. Privatization began early and was brought to near-completion within a decade, and, in these regimes, was regulated in such a way that prevented widespread asset appropriation by incumbent elites. These regimes exhibit the highest observed levels of elite turnover in both political and economic posts, and the new private business elite is not dominated by figures from the old regime.3

Table 1.1 Estimated private sector share of Gross National Product, selected transitional economies, 1999

A second type is illustrated by Russia and the Ukraine. In the case of Russia, the greatest challenge to Soviet rule was from within the (Moscow) Party apparatus, and its early elections created a political elite that exhibited much larger proportions of the former communist hierarchy than in Central Europe. As the communist party lost elections and as the economy was privatized, the old appointment system and party bureaucracies disappeared. Privatization was rapid but poorly regulated and heavily influenced by incumbent managers and economic bureaucrats, who managed to retain control of privatized state assets and turn themselves into a new corporate elite. This generated a political elite that included large numbers of old regime survivors, and a private business oligarchy with firm roots in the old system.4

A third type is prevalent in several regimes that emerged from the collapse of multi-national federations. These regimes were born when regional communist parties withdrew from the Soviet Union or Yugoslavia, changed their names, and continued to rule as nationalist dictatorships with little initial organizational change. In such states (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia), there was very little elite turnover, but the abandonment of the commitment to public ownership by old regime figures led to high rates of asset appropriation and extensive corruption by top political officials and their families.5

This brings us to China, which is the leading example of a fourth type. China’s party hierarchy has survived unchanged, and despite extensive market reform, it has maintained its commitment to public ownership for a very long period. This commitment, coupled with effective political restrictions against the kind of spontaneous privatization typical in the second and third types above, has led to considerably lower rates of movement from political posts into private business than have been observed in Russia and other former Soviet Republics. Asset appropriation by officials does, indeed, occur (as it does in all these regimes), and the practice has been documented and is widely discussed by students of China.6 However, the rates at which public assets have been appropriated as private property in China are much lower than in Russia and other regimes, where a new private business oligarchy has already emerged and is dominated by old regime figures. Vietnam shares these features with China, but so do several former Soviet republics whose economies have done poorly, where the former communist party holds the balance of political power and where privatization of public assets has proceeded very slowly.7

This brief comparative tour of regimes and elites highlights a central fact about China’s future political and economic trajectory: despite rapid growth and prolonged market reform, it has yet to undergo the twin processes of political change and privatization that have already occurred in the vast majority of comparable regimes. Undertaking these transitions after a period of rapid economic restructuring and growth is historically unprecedented, and has no parallel in the experience of regimes that have already completed these transitions. There are, therefore, good reasons to consider that the kind of collapse observed in the rest of the socialist world is not the most likely outcome in China’s near future. Given the Chinese Communist Party’s remarkable durability, we need to ask what changes are taking place within the party that might anticipate future political changes, either through an erosion of the party’s capacity to rule or – less commonly considered – its evolution into an agent of creative political change. And given the sharply contrasting experiences of regimes that collapsed and rapidly privatized their assets, the way in which privatization is handled in the years to come will have important consequences for China’s future economic health and political cohesion.

China’s current political elite

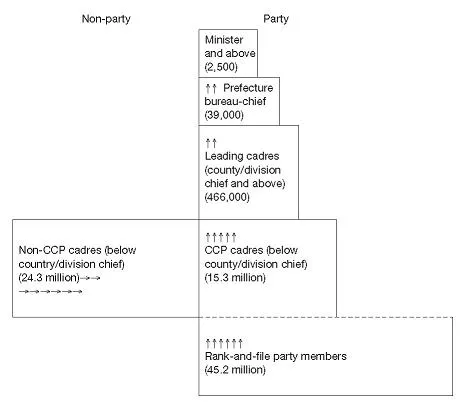

A definition of China’s political elite would include all cadres at the rank of county magistrate or division chief and above. In 1998, there were roughly 500,000 people who held such positions: 900 in the central party apparatus, 2,500 with the rank of minister or provincial governor, another 39,000 down to the level of prefecture or bureau chief, and the remaining 466,000 down to the county and division chief level. Virtually all of these people – over 95 percent – are members of the Communist Party.8

This political elite commands a national bureaucracy of 40 million cadres below the level of county magistrate/bureau chief (see Figure 1.3). Only a minority of these ordinary cadres are party members – 15 million, or 38 percent.9 Given the nature of China’s cadre appointment system, all appointments into the political elite of 500,000 are made from among these 40 million ordinary cadres, who constitute the pool of potential elite appointees. The vast disparity of party membership figures between the political elite and ordinary cadres in the civil service suggests that appointments into the elite are made almost exclusively from among those ordinary cadres who have already joined the party. One would therefore expect that party recruitment would focus heavily on the 25 million ordinary cadres who have yet to join the party, and such cadres who wish to advance into the elite will strive to join the party.

Figure 1.3 China’s party-state hierarchy

This brings us to the party organization itself. It has a total of 60 million members (c.1998). We tend to think of the party as the elite, but this is not accurate. True, party members comprise only 8 percent of the total adult population, but only 25 percent of party members are cadres (15 out of 60 million). Many of the remaining 75 percent, to be sure, do hold positions of responsibility – especially in China’s 800,000 villages (where leaders below the township level are not on state salaries), or in workplaces where they often serve as group leaders or shift supervisors. But the distinction still holds: party members are “elite” only in the sense that they have a special relationship with the party hierarchy and are the group from which future state cadres and, eventually, the political elite, will be chosen. The great majority of party members have ordinary occupations that involve no real authority.

This sketch of the most politically influential groups in Chinese society highlights some key relationships that will vitally affect the country’s future path of political change. The political elite of 500,000 cannot rule the country unless it can retain the obedience of 40 million state cadres – especially the 38 percent of whom are party members. Moreover, the state bureaucracy cannot rule unless it has the active cooperation and allegiance of the 45 million party members who work outside the state bureaucracy. If these three groups act in concert, and if the elite maintains the discipline of state bureaucrats and the allegiance of party members, it can withstand challenges from other groups in society, even in periods of economic hardship and social upheaval. If, however, challenges from other groups stimulate a defection of the party membership and parts of the state bureaucracy, the elite is in real trouble (this is what happened in China, temporarily and briefly, in May 1989). But our sketch also implies that challenges to the elite, and the impetus for political change, need not come from outside these influential circles. In fact, the dependence of the elite on party members and ordinary cadres i...