- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Money, Credit and Price Stability

About this book

Beginning with the development of credit-money theory in the twentieth century, Paul Dalziel derives a model that explains how interest rates are used by authorities to maintain price stability. His conclusions suggest ways in which the current policy framework can be improved to promote growth, without sacrificing that stability.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Money, Credit and Price Stability by Paul Dalziel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

Business allgemein1 The quest for price stability

One of the oldest ideas in economics is the quantity theory of money; indeed, The New Palgrave describes the proposition that increases in the stock of money eventually cause prices to rise in the same proportion as being ‘older than economic theory itself’ (Bridel, 1989, p. 298). With suitable extensions to recognise the impact of changes in the volume of economic transactions or the velocity of circulation (Fisher, 1911), and more generally the impact of changes in real money demand (Friedman, 1956), this long-standing theory remains the starting point for much modern analysis in monetary economics. In particular, its strong causal link between changes in the money supply and changes in the price level offers a clear strategy for achieving price stability: those responsible for controlling the money supply should be given a statutory duty to implement policy that is consistent with a pre-announced low inflation target. New Zealand was the first country to reform its central bank legislation along these lines (in 1989), and its example has been followed by others since (including Canada in 1991, the United Kingdom in 1997 and the European Central Bank in 1998). The result has been a clear improvement in inflation performance by the end of the twentieth century compared with the previous three decades (see Figure 1.1).

Despite the success of the new monetary framework in controlling inflation, there remains a puzzle that this book seeks to address. To be effective for policy purposes, the quantity theory of money requires that the central bank has the ability to determine the nominal money supply exogenously (that is independently of other economic influences) so that its growth can be set to be consistent with the bank’s inflation target. In practice, however, monetary authorities do not have direct control over the monetary aggregates, and indeed the English-language central banks that attempted to target money supply growth rates in the 1970s abandoned that practice in the 1980s. The difficulty is that virtually all money in modern economies takes the form of bank deposits that are created, not by the monetary authorities, but by the credit extension activities of private sector banks. Consequently central banks are able to influence the volume of this credit-money only indirectly, particularly through policy-induced changes in the banking system’s base interest rate. Analysing the critical roles of credit in determining money supply growth and as a key component of the transmission mechanism from monetary policy to price stability is the primary subject of this book and provides its title, Money, Credit and Price Stability.

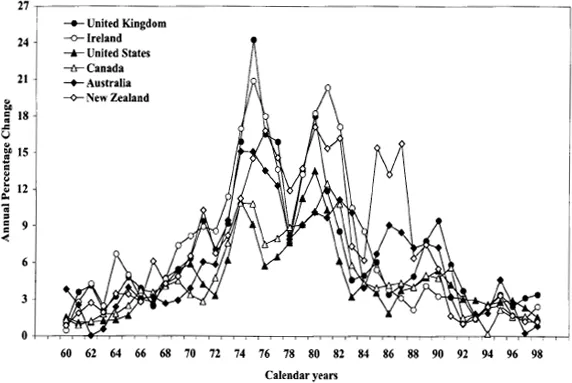

Figure 1.1 Consumer price inflation of English-language OECD countries, 1960–98 Source: International Monetary Fund International Financial Statistics, October 1999

In contrast to the exogenous money model underlying the quantity theory of money, the framework adopted in this study is termed the ‘endogenous money’ model. Since the creation of credit-money by the financial system is governed by economic incentives, rather than any mechanical relationship to the monetary base, previous studies using the endogenous money framework have typically denied any policy role for the quantity theory, arguing instead that inflation is the result of other considerations such as excessive growth of aggregate demand (Kaldor, 1970: p. 1), income distribution conflict (Weintraub and Davidson, 1973: p. 1125) or self-fulfilling expectations (Black, 1986: pp. 539–40). This book argues that this rejection is too strong, and demonstrates that once the central bank’s base interest rate determines the aggregate money stock indirectly – by affecting the lending activities of banks – the quantity theory of money can then be used to show how the price level is determined through the portfolio decisions of wealth holders.

Although this study may therefore be considered as a reconciliation of the exogenous and endogenous approaches, it also draws conclusions that are likely to be anathema to both sides of this sometimes bitter debate. In particular, exogenous theorists are likely to object to the result that monetary policy may not be neutral with respect to real economic growth, even in the long run, whereas endogenous theorists may object to the implication that inflation can be a genuine monetary phenomenon that can be controlled by the central bank. With this in mind, the chapters that follow seek to explain at each step of the argument how the model is derived from the previous work of important monetary theorists, and how it is consistent with actual macroeconomic experience. In particular, the analysis in this book integrates the money and real sectors of the economy into a Keynesian model of finance, growth, inflation and monetary policy that is a considerable development on its predecessors.

The remainder of this chapter elaborates on these major themes of the book. The first section describes the inflationary experiences of the six English-language OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States) after 1960, and it relates how initial efforts to control inflation through incomes policies, price controls and monetary targeting gave way to the current policy framework based on base interest rate adjustments and inflation targeting. The next section then briefly summarises the exogenous and endogenous money models, providing representative quotations in each case to illustrate the corresponding fundamental assumptions being challenged in this study. The final section provides a précis of the chapters that follow, in order to present an overview of how the book will present its model and conclusions.

The rise and fall of inflation in the late twentieth century

Figure 1.1 presents time series data for the annual consumer price inflation rates of Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States between 1960 and 1998. These data reveal low inflation rates for most of the 1960s, generally below 5 per cent. In the first half of the 1970s, however, inflation rates rose in all six countries, peaking at approximately 11 per cent in Canada and the United States and between 15 and 25 per cent in the other four countries. The first reaction of policymakers was a two-pronged approach based on incomes policies to slow wage or price increases and money supply growth targets to guide monetary policy.1 In the United Kingdom, wages and prices were subject to statutory controls from November 1972 to July 1974, and the Labour government announced annual wage increase guidelines in each of its Budgets from 1975 to 1977. In mid-1976, the government also announced a growth target for the broad money supply (M3), a practice that continued with some refinements in subsequent years. In the United States, there was a sixty-day price freeze in June 1973, followed by informal incomes policies until President Carter, in October 1978, announced formal standards for wage and price increases to be administered by a Council on Wage and Price Stability. In 1975, Congress passed a resolution requiring the Federal Reserve to begin publishing and reporting on its success in achieving targets for growth in the money supply aggregates. In Canada, the government announced a three-year anti-inflation programme in October 1975, which included mandatory wage and price controls monitored and administered by the Anti-Inflation Board. In the same year, the Bank of Canada began announcing growth targets for the narrow money supply (M1). In Australia, a three-month price and wage freeze was imposed in April 1977, followed by partial indexation of wages set by the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission, while in August 1976 the Treasurer began the practice of announced projected growth in M3 over the twelve months to the following June. In New Zealand, a series of wage controls were imposed and small General Wage Orders were awarded throughout the second half of the 1970s, and the government continued to rely on regulated wage and price control measures right up until the early 1980s.2

The incomes policies in the United Kingdom and the United States ended with changes of government in 1979 and 1980, leading to a much greater emphasis on setting and achieving money supply growth targets. In the former country, this was based on the government’s Medium Term Financial Strategy, which included targets for growth in the broad money supply, M3. In the United States, the Federal Reserve announced in October 1979 a greater dedication to achieving its money growth targets, and changed its major policy instrument to controlling non-borrowed bank reserves in line with the new focus. Ireland, Australia and Canada also turned towards a greater reliance on monetary restraint in the early 1980s to achieve disinflation. Ireland joined the European Monetary System at its inception in 1979 to boost the credibility of its commitment to monetary discipline. Canada successfully achieved pre-announced reductions in its monetary growth target between 1978 and 1981, and maintained tight monetary policy (despite monetary growth being below target) to offset inflationary pressures in 1982. Australia was not so successful in meeting monetary growth targets in the late 1970s, but in 1982 accepted real interest rates that were higher than had been seen before in that country in order to reduce inflation. New Zealand was alone among the six countries in not introducing policies of monetary disinflation; instead the Minister of Finance announced a universal incomes and price freeze in June 1982, which remained in place until February 1984. Figure 1.1 records that inflation in these six countries was reduced from 10–20 per cent in 1980 to 4–9 per cent in 1984.

Inflation rebounded in New Zealand after the end of its price freeze until monetary disinflation was implemented in earnest after April 1988 (Sherwin, 1999: p. 73). Australia also returned to a greater emphasis on an incomes policy following a change of government in 1983, accepting a somewhat higher inflation rate in the process. The other four countries continued to use monetary restraint over the next three years so that by 1987 inflation was down to 4.4 per cent in Canada, 3.1 per cent in Ireland, 4.2 per cent in the United Kingdom and 3.7 per cent in the United States. This second wave of monetary disinflation, however, was accompanied by a growing disenchantment with the practice of monetary targeting. Canada in 1982 found that the narrow money supply was well below its target growth rate at a time when inflationary pressures were high, and so monetary targeting was abandoned. In Australia, the opposite occurred – growth in the broad money supply for 1984/5 was 17.5 per cent compared with a target range of 8–10 per cent at a time when inflation was judged to be acceptable, and so monetary targeting was abandoned in early 1985. In October 1985, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the United Kingdom delivered his ‘Mansion House Speech’, in which he declared that the sterling M3 target had been effectively suspended (although projected ranges continued to be published) after several quarters of high growth that had not been reflected in rising inflation. In 1987, the United States abandoned setting target growth rates for its M1, although it continued to publish broad money supply growth targets, following the collapse of prior empirical relationships between money and prices (Friedman and Kuttner, 1996).

There are two broad explanations for the ending of monetary targeting during the 1980s. The first emphasises the possible loss of political will for achieving genuine price stability as the employment costs of monetary disinflation became apparent.3 Rates of unemployment for five of the above countries peaked at around 10–12 per cent during their disinflations, and rose above 18 per cent in Ireland. Such high levels of unemployment created political pressures in favour of relaxing monetary policy once inflation had been reduced to moderate levels. The second explanation emphasises the way in which financial deregulation made previous relationships between the monetary aggregates and nominal gross domestic product growth totally unreliable. Thus when there was a conflict between a pre-announced money supply growth target and the monetary authorities’ projected inflation rate, the authorities began to place more and more weight on achieving their desired rate of inflation. In short, central banks began to move towards direct inflation targeting, rather than relying on any intermediate targets for money supply growth.4

Consistent with the first explanation, inflation rates in some countries began to rise again towards the end of the 1980s, most notably in Britain, which experienced inflation of 9.5 per cent in 1990. This led to a period of renewed monetary restraint, accompanied by reforms that formalised the emerging practice of targeting inflation directly. In Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, price stability is now explicitly described as the sole objective of monetary policy (see, for example, Poloz, 1994: pp. 21–22; Dawe, 1990; Bank of England, 1993), and this commitment is accompanied by underlying inflation targets of 1–3 per cent, 0–3 per cent and 2.5 per cent respectively. Ireland enshrined price stability as the primary objective of its central bank in 1998 as part of the necessary steps to be a founding member of the European System of Central Banks in January 1999 (Bank of Ireland Annual Report, 1999: p. 24). In Australia and the United States, the governing legislation continues to mention employment or output goals, but statements by senior office holders have for several years made it clear that these will not be pursued at the expense of inflation (see, for example, Fraser, 1994; Greenspan, 1994). The Reserve Bank of Australia has also set a preannounced inflation target of 2–3 per cent on average over a normal business cycle. By the mid-1990s, this reformed framework was successfully keeping inflation at low levels in all the countries shown in Figure 1.1.

Exogenous and endogenous money theories

The monetary reforms of the 1990s were based on the widely accepted economic theory that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon and monetary growth is always and everywhere a government phenomenon. This can be illustrated with a number of representative quotations from the relevant literature:

Whatever was true for tobacco money or money linked to silver and gold, with today’s paper money, excessive monetary growth, and hence inflation, is produced by governments. In the United States the accelerated monetary growth during the last fifteen years or so has occurred for three related reasons: first, the rapid growth of government spending; second, the government’s full employment policy; third, a mistaken policy pursued by the Federal Reserve System.

(Friedman and Friedman, 1980: p. 264)

The government determines the nominal money stock at the start of period t to be the amount Mt. No private issues of money are considered.

(Barro, 1983: p. 3)

We assume that the policymaker controls an instrument – say, monetary growth, μt – which has a direct connection to inflation, πt, in each period…. In effect, we pretend that the policymaker chooses πt directly in each period.

(Barro and Gordon, 1983: p. 594)

Inflation and taxes are set respectively by the central bank (CB) and by the fiscal authority (FA). Within the framework of this model, the hypothesis that the CB directly controls inflation amounts to assuming that money demand is not affected by fiscal policy.

(Alesina and Tabellini, 1987: p. 622)

[There are] two political parties in this economy…. It is assumed that the party in power is able to directly control the inflation rate.

(Waller, 1989: p. 424)

For simplicity, [assume] that the policymaker controls the actual inflation rate exactly and can predict future expected inflation rates exactly.

(Grossman, 1990: p. 167)

Given that nobody is in favour of high inflation for its own sake, the assumption that governments control the rate of money growth – and hence inf...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 The quest for price stability

- 2 What is money?

- 3 Credit-money and inflation

- 4 Critical realism and process analysis

- 5 Keynes’s revolving fund of investment finance

- 6 Davidson’s analysis of the revolving fund

- 7 A theory of credit-money inflation

- 8 Inflation and growth

- 9 Fiscal deficits and inflation

- 10 Monetary policy and price stability

- 11 Conclusion

- Appendix: Notation

- Notes

- References

- Index