![]()

1

THE ROOTS OF CONFLICT

Geopolitics, historical happenstance, and brutal realpolitik have shaped Bosnia. However, in order to understand Bosnia’s history and its significance for its contemporary situation, one must remember at least two things. The first thing to recall about Bosnia – about the whole South Slav experience, as a matter of fact – is that the ancestors of its major actors, the Serbs, Croats, Muslims, and others, entered the Balkans in about the sixth century, and at that time they were not differentiated into those various ethnic groups. History had yet to sunder their connections or to create national divisions among them. During the medieval period it was difficult to differentiate Serbs from Croats, although contemporary politicians and intelligentsia have tried to do just that in order to justify their claims to certain territories. Only in the nineteenth century would such terms as “Serb” or “Croat” take on greater significance to the populations to whom these terms applied than their local or regional identities.1 The vagaries of history would gradually differentiate them in regard to certain linguistic niceties, religion, and social custom, but the South Slavs seem to have originated from the same general area of the world and thus were not mutually exclusive aliens to each other.

The second important key to understanding Bosnia is that after a rather short medieval interregnum of independence, indeed of Bosnian empire, and until the last decade of the twentieth century, it has been the subject of one or another greater power: the Ottoman Empire; Austria-Hungary; the Serbs, who dominated the first Yugoslavia; the Croatian fascists in the Second World War; the communists in the post-Second World War era; and currently the international community, as a protectorate. While Susan Woodward has observed that “having a history of overlords is not the same as needing” an overlord,2 nevertheless, Bosnia has not experienced much autonomy since that early period.

The setting

Bosnia’s geographical setting has had an immense influence on its historical and socio-political development. The area of the former Yugoslavia was approximately the size of the state of Wyoming. While the territory of what was Yugoslavia has been in the crosshairs of history since its first habitation, no area has been more so than its “heart,” Bosnia and Herzegovina, although at the time of this writing Macedonia is beginning to come into contention again for that dubious honor. Bosnia has been threatened by conquest throughout its history and has been fought over by competing empires spouting opposing ideologies or nationalist aims. Its forbidding mountainous terrain successfully deterred some would-be conquerors and repelled the less-hardy ideologues and proselytizers, thus marking Bosnia as a transitional area. However, it was also long an economically active region, even from Roman times, which made it a prize possession. Mining of copper, lead, arsenic, silver and quicksilver, salt, and especially iron ore dominated the economy, although the manufacture of knives, swords, and leather goods and the fur trade constituted Bosnia’s production. Sarajevo was then an internationally known trade center.3

As an important European continental gateway to the Middle East,4 the Balkans,5 nevertheless, were considered somewhat peripheral to Western Europe. However, with the collapse of communism, the geopolitics of the region exerted strong influence on Yugoslavia, marking it as a “shatter-belt.”6 Bosnia, in particular, was affected. As was wryly observed, “When the Berlin Wall came down, it fell on Bosnia-Herzegovina.”7 Thus, European politics have influenced Bosnia, just as Bosnian politics have influenced Europe. As a matter of fact, as the coming pages will illustrate, one might easily agree with John B. Allcock that the Balkans have, throughout history, been the stage upon which European countries have played out their larger conflicts.8

The early years

The early South Slavs migrated throughout the Balkan Peninsula, possibly from Iran (as indicated by linguists studying their tribal names).9 They farmed the land, creating small organized communities, and then increasingly larger entities, intermarrying with the local population. Christianity was introduced into the Balkan Peninsula beginning around the seventh century, but only in the ninth century did missionaries from Rome succeed in converting the indigenous inhabitants of what we now know as the Croatian lands. Missionaries from Byzantium, such as Cyril and Methodius, successfully preached the gospel to the lands we currently call Serbia also during the ninth century. However, because of its mountainous, and, thus, fairly impenetrable areas, it is unlikely that either of the rites represented by the missionaries was able to supplant totally the pagan religious practices of remoter areas of Bosnia. While the region lay between the two major areas of missionary work and likely produced many devoted Catholics and Orthodox in Bosnia, Bosnia’s faith was probably not firmly linked with either Rome or Constantinople.

During the early Middle Ages, however, Bosnia gradually drew closer to the Catholic Church. Franciscans were permitted to set up a Bosnian mission, and most rulers of Bosnia were at least nominally Catholic. Nevertheless, it appears that even at this time a proportion of the Bosnian population was following a rite that could not be considered precisely Catholic. As a matter of fact, Hungary continued to declaim the Bosnian Church as heretical, using what it deemed to be Bosnia’s flawed religious rites as an excuse for launching periodic crusades to try to incorporate Bosnia firmly into its possession. According to John V.A. Fine, Jr.,10 the Bosnian Church appears to have been a religious organization that reflected the imperfect missionary work in the remoter parts of Bosnia, although many scholars argue that the predecessors of today’s Bosnian Muslims were instead members of a heretical group known as the Bogomils.11

Bosnia experienced a succession of external rulers from the middle of the tenth through the late twelfth centuries. Byzantium, Charlemagne’s Franks, Croatia, Montenegro (then called Duklja), Serbia, and Hungary all briefly conquered parts of Bosnia but left little impression on the local populace. However, at the end of the twelfth century, Hungarian control over Bosnia was firmly established in the person of a ban or governor. This ban, however, served at the pleasure of the Hungarian monarch less and less and became increasingly independent.

Herzegovina (Hum), under Serbian rule for a large part of the medieval era, was acquired by Bosnia’s Ban Stephen Kotromanić (1322–53) in the mid-fourteenth century. He opened copper, silver, gold, and lead mines there, which helped to make Bosnia an economically viable unit.

Bosnia’s independence was solidified when in 1377 Ban Tvrtko (1353–91) proclaimed himself King of Bosnia and Serbia (although he and subsequent Bosnian rulers controlled very little Serbian territory). During Tvrtko’s reign, Bosnia expanded southward toward the Adriatic and became a very powerful state within the region, taking advantage of Hungarian and Serbian weakness in the face of continued Ottoman onslaughts. However, Tvrtko’s death spelled the end of Bosnia’s strength and independence. While Bosnia did not dissolve into statelets, the unity that had been forged previously was lost. This meant that Bosnia was easy prey for those who wished to dominate it.

In the early fifteenth century the Ottoman Turks began to nibble at the edges of the Bosnian lands. Having defeated the Serbs in the late fourteenth century, the Turks were able to extend their influence into Bosnia relatively easily. Finally, in 1463 Bosnia fell to the Ottoman Empire, introducing a third religion, Islam, into the Bosnian mix of Catholicism and Orthodoxy.12

The Ottoman period

The medieval Bosnian state had enjoyed long periods of autonomy. When it was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in the fifteenth century, it was initially only loosely incorporated into the imperial structure. Bosnia’s borders remained relatively stable as a province of the Ottoman Empire.13

The structure of the Ottoman Empire exerted major influence on the development of Bosnia in general, as well as on the relationship among its various inhabitants in particular. The largely rural Bosnian area learned to accommodate the urbanized Ottoman feudal society with some difficulty. The kmets (serfs) were mainly Christians and, as feudal dependents, were unable to own land. Only persons of the Muslim faith could acquire and inherit land and other property or work for the state as soldiers or scribes, or as merchants with state protection for their goods. The Bosnian Muslims generally controlled the land for the Empire, receiving in return a fair amount of discretion in local matters. Some heavy industry flourished in Bosnia under Ottoman rule, and there was some textile manufacture, although it was weak. But, in general, Bosnia under Ottoman rule was uneven in its industrialization,14 particularly as it lacked essential infrastructure, domestic markets, and a skilled labor pool.

While some Muslim nobles arrived in Bosnia with the invading Ottoman Turks, most Bosnian Muslims were indigenous Islamicized Slavs. Islam was open to people of any national background, so those who wanted to protect the family lands, or who desired to acquire social, political, and financial advantages, became Muslim. Furthermore, those whose allegiance to the Christian churches was minimal anyway might have found the dynamic and well-ordered organization of Islam tantalizing. Whatever the individual reasons for Islamization, it is important to remember that most of those who became Muslims in Bosnia were originally indigenous Slavs – from the same gene pool as those who remained Christian under Ottoman rule. Within the Ottoman Empire, religion, not national identity, was the most important personal defining feature. Thus, any popular tensions during the years of Ottoman rule were not the result of ethnonational hatreds.

The Christian population was permitted a measure of self-government under Ottoman rule through the millet system. Under their own leaders, who were considered agents of the Ottoman administration, the Christian population was organized into self-governing communities for religious, social, administrative, and legal purposes. Requiring little social loyalty from their kmets, the Ottoman Turks permitted the Christian population to solidify around these leaders and their own rituals, allowing the growth of what would later become national particularity.

The Muslim population of Bosnia, on the other hand, was subject to Shari’a law and, along with the privileges of being a part of the ruling aristocracy because of religious affiliation, was subject to the rules of the Ottoman administration. This situation finally caused the Bosnian Muslim population to suffer a crisis of loyalty. On the one hand, their religious affiliation was the source of their influence and privilege within Bosnia, and, as such, was the foundation of loyalty to the Ottoman regime. On the other hand, their base of power was within Bosnia proper. Eventually, when the Ottoman Empire was already in decline in the eighteenth century, the Bosnian Muslims rebelled against Ottoman attempts to alter agricultural practices and to reform the socioeconomic, military, and administrative systems in their region through the Tanzimat and later reform programs. Muslim feudal landowners in Bosnia created private armies to protect their properties and privileges. Bosnian Muslim resistance became allied with the increasingly militant restiveness of the non-Muslim kmets, who were infected with nationalistic fervor that was manifested in a number of anti-Ottoman rebellions in the nineteenth century.

External forces, however, were also at work to weaken the Ottoman Empire. Serbia had already gained increasing autonomy from the Ottoman Empire. Peasant rebellions in the early nineteenth century culminated in its grant of freedom from Ottoman rule in 1878 by the Congress of Berlin. The Serbian quest for independence had been long and arduous and had fired the aspirations of Serbs throughout the Ottoman Empire. Therefore, when autonomous Serbia supported the anti-Ottoman kmet uprisings within Bosnia, many kmets, whose territorial aspirations were frustrated under the Turks, considered Serbia the epitome of freedom. They yearned to unite with Serbia outside of Ottoman rule. Many of the Serbian political elite deemed Bosnia to be Serbian land since there were so many Serbs living there15 and aspired also to encompass Montenegro, Kosovo (Old Serbia), Vojvodina, Croatia’s Serb-populated Krajina,16 and Macedonia (Southern Serbia).

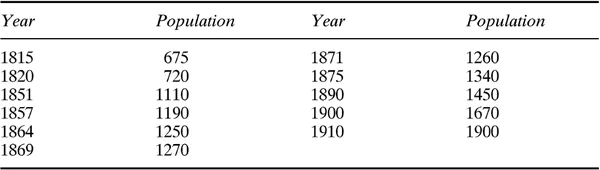

Table 1.1 Bosnian population, 1815–1910 (in thousands)

Source: Michael Palairet, The Balkan Economies c. 1800–1914: Evolution without Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 11–12, 20.

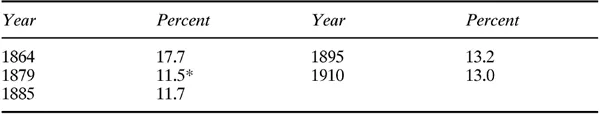

Table 1.2 Urban population of Bosnia as percent of total population

Source: Michael Palairet, The Balkan Economies c. 1800–1914: Evolution without Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 26.

Note

*Palairet blamed the downturn in urbanization on the Austro-Hungarian occupation, during which Muslims left Bosnia in large numbers “partly because of limitations on land rights, partly because of an abrupt decline in urban commerce” (The Balkan Economies, p. 31).

The realization of the Greater Serbian dream, however, was prevented by the machinations of the great powers. They feared both the destabilizing effect of the sudden destruction of the Ottoman Empire, as a result of the successes of the peasant liberation movements, and a concomitant growth of Russian influence in the Balkans. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, therefore, the great powers decreed that European stability would be maintained by the slow and managed dismantling of the Ottoman Empire, disregarding the desires of the indigenous population.17

Bosnia was given to Austria-Hungary, not to Serbia, to ease its access to the Dalmatian Coast and to slow Serbian expansion within the Balkans. Habsbu...