![]()

1 Introduction

This report focuses on building a ‘universal-access, developmental, social welfare system’. The term ‘welfare’ signifies the conditions conducive to improving quality of life and the feeling of happiness, including both material wealth that improves people's physical well-being, and factors affecting their free intellectual and mental development. The term ‘social welfare’ refers to the social institutions under which the government seeks to provide citizens with funds and services to ensure a certain standard of living and the best possible improvement in quality of life. The term ‘social welfare’ has a broadly defined and a narrowly defined meaning. In a broad sense it means the various policies and social services designed to provide a better life for all citizens. In a narrow sense it refers to provisions that the government makes for vulnerable groups. This book addresses social welfare in the broader sense. It treats ‘social welfare systems’ as a combination of all the institutional arrangements relating to social welfare policies and services that are available to members of a society.

The proposed new social welfare system is intended to serve each and every Chinese citizen, including inhabitants in rural areas and rural migrant workers. It is intended to cover pensions, medical care, education, employment, housing and the minimum living allowance. The system is termed ‘developmental’ since it is intended to move forward incrementally and be increasingly human-oriented. It brings ‘upstream interventions’ into the sphere of welfare, including expanding education, promoting good health, and assistance in finding employment. It calls for making greater use of public funds in the specific arena of human capital. In so doing it replaces the traditional compensation-oriented welfare system with one that benefits from, and in turn fuels, economic growth.

China has already entered a new stage of development. The 30-year period of ‘reform and opening-up’ has brought massive change to China's economy, the Chinese people and their way of life, and it has greatly strengthened the material basis for our strategic policy of harmonious development (Wang Mengkui, 20061). Acknowledging the achievements, however, does not mean that we can neglect the acute social problems and challenges that exist. China has also entered a period of multiplying contradictions. How to address social conflicts in a proper manner and maintain the harmonious development of society has become a major concern of our social welfare system.

Four major challenges face our economic development. First, our demographic trends are going to have a severe impact upon the development of a harmonious society. The base quantity of our population is very large, we have a huge number of inadequately educated people, and an ageing society that is not yet well-off. All of these multiply social and economic problems and place enormous pressures on the social welfare system. The problems include how to handle employment, pensions and medical care. Second, with growing industrialization, urbanization and market-oriented trends, people's mobility has greatly increased, both in terms of moving between rural and urban areas and among various industries and occupations. The migration of rural workers into cities has brought severe challenges to our traditional social welfare system which continues to apply a ‘dual treatment’ to urban and rural people in terms of its distribution of public finance and public services. Third, in the course of transitioning from one system to another, our income distribution system is less than perfect and has resulted in widening income disparities. The rural poor are urgently in need of social welfare. Fourth, globalization has brought its own risks. China has become a major player in international trade and therefore is more and more reliant on global markets. Economic crises in other countries and turbulence in the global financial markets have both direct and indirect impacts on our domestic economic growth and the stability of our employment. They impose a very definite negative impact on the lives of Chinese people.

Traditionally, Chinese people believe that the respect one has for the elderly in one's own family should extend to respect for elderly in other people's families, and that love of one's own children should extend to love for children of others as well (Mencius). According to Confucius (The Book of Rites – The Conveyance of Rites), ‘One does not love one's own parents only, nor only one's own sons. [We] enable the aged to age, the strong to use their strength, the youth to mature, and we provide for widows, orphans, those who are alone, and the crippled.’ These beliefs are very close to the mission of today's social welfare system.2

Over the course of centuries, various social welfare systems have been developed in the western world, starting with the Elizabethan Poor Law in England. In recent decades, the interaction between systems has begun to result in certain convergences, while at the same time there are diverging trends. On the one hand such basic principles as universal coverage, equity [fairness] and sustainability are globally accepted. On the other hand, more and more people believe that the social welfare system in a country must be in alignment with its stage of social development and basic values.

The goal in building this ‘universal-access developmental social welfare system’ is to go further in improving the fair distribution of the outcomes of China's economic development, and to enhance the sustainability of that development. It is to build a ‘moderately prosperous society’ in a comprehensive sense. The requirements of our situation dictate that we adopt a system that can adapt to our fast-growing economy and its consequent social changes.

This report envisions that, with hard work over the next 12 years, by the year 2020 we will have built a welfare system that meets the needs of our country and serves its citizens. That system will include expanded free compulsory education, pensions and basic medical care programs for all citizens, affordable housing and minimum living allowances for all low-income families in urban and rural areas as well as certain rural migrant workers, and employment assistance and unemployment insurance for all workers. This social welfare system is an important institutional guarantee for the comprehensive and coordinated development of China's economy and society.

In view of the global financial crisis that has affected our country's economy, accelerating the improvement of the social welfare system is of particular significance. In order to deal with the consequences of the crisis, China's government has recently passed a series of policies to encourage domestic demand. We should recognize that these policies pave the way for starting many welfare measures in advance of their earlier timetables. Furthermore, the benefits these policies deliver will depend, to a large extent, on improving our social welfare system. Therefore, we are facing an opportune time to enhance our social welfare system. This will not only help ease people's worries about their jobs, and encourage greater consumption, but the process of implementing the system will in itself serve to stimulate domestic demand. It will bring about a great number of investment and employment opportunities. Priority should therefore be placed on this system as the best way to improve people's lives.

China's socioeconomic development: reflections on how things were

Profound changes in social and economic structures

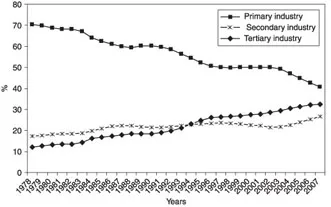

Thirty years of economic reform in China have spurred rapid economic growth and brought about tremendous changes in the economic structure. The contribution of primary industries to GDP dropped sharply from 28 percent in 1978 to 11.3 percent in 2007, while the contribution of the tertiary industries gradually rose, from 23.9 percent to 40.1 percent during the same period.3 Changes in industrial structure were mimicked by those in employment structure—the period saw a constant decline in the percentage of primary-industry employees and a steady increase in the percentage of tertiary-industry employees. Between 1978 and 2007, primary-industry employment as a percentage of the total declined by nearly 30 percent, while the secondary and tertiary industries both showed an increase. Tertiary industries in particular reported an increase of nearly 20 percent (see Figure 1.1). However, compared to industrial structure in GDP, the structure of employment still needs improvement, since the percentage of people working in the primary industry is still higher than that industry's contribution to GDP. This signifies that adjustments in employment structure will continue in coming years, and the number and percentage of people engaged in the primary industry will further decrease.

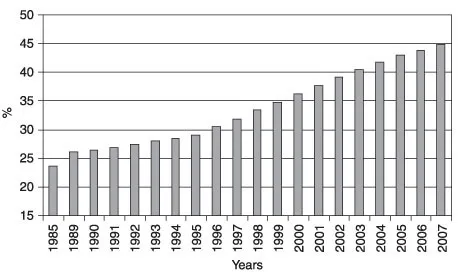

One effect of changes in employment structure is the migration of people and mobility of the labor force, moving from rural areas to urban areas and among different regions. The result has been a radical increase in the urban population in China. This population increase in cities is a positive part of the urbanization process, but it also places public services in cities under tremendous pressure. Between 1985 and 2007 the number of Chinese living in urban areas increased by over 20 percent (see Figure 1.2). It should be noted that a large number of the urban population are rural migrants who have come to cities since the implementation of reform and opening-up policies, yet the large majority of these people have not received an urban ‘residency card’, i.e. officially become urban residents. We estimate that nearly 200 million rural laborers work in a place other than their hometown. This includes 130 million who are rural–urban migrants working in cities. Two trends have recently been observed with regard to rural migrant workers. One is that a large percentage of these people work all year round at a place other than their original home, and are thereby completely divorced from farming. The other is that a significant number of these people are moving to urban areas together with their families to engage in non-farming activities. More and more ‘migrant’ rural workers have changed from being peasant-workers who split their time between farming and non-farming jobs to full-time non-agricultural workers. Their employment versatility has weakened as a result. A permanent migration has gradually replaced a seasonal migration. The two-way flow between urban and urban areas has changed as more and more rural workers are integrating into urban environments by settling down in towns and cities.4

Figure 1.1 Percentages of people working in different industries in China, 1978–2007.

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2008) China Statistical Abstract 2008. Beijing: China Statistics Press, p. 44.

China's family structures are also undergoing enormous change, characterized most importantly by the decreasing size of the family in both urban and rural areas. In 2006 the average family size in China was 3.17 persons, down from 4.81 in 1973. In Beijing the number in 2006 was 2.64 and in Shanghai it was 2.65. The average family size in China comes close to that in developed countries such as the United States and Canada, where a family has around three members on average.5 As family structure changes, more and more ‘empty nests’ appear in which elderly parents are living alone after their children leave home. When an older person is widowed the situation can be even worse. In rural areas the elderly were once supported by family members, while now they are not. Once the elderly are unable to work they face the very real risk of poverty, with absolutely no means to sustain their lives (Tang Can, 2006).

Figure 1.2 China's urbanization process (the urban population as a percentage of the national total).

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2008) China Statistical Abstract 2008. Beijing: C...