1 Introduction

The role of corporate governance and finance in innovation

1.1 How do nations get technological advantage?

The aim of this book is to show how far a set of institutions and relationships, which we call corporate governance, together with a closely related set, which we call finance, can go to explain the technological advantage of nations. Corporate governance we will define simply as who controls firms, and how—although that begs many questions, which will be answered later in this chapter and in Chapter 3. Finance is probably clear enough for the moment. The technological advantage of nations, we will dwell on now. The phrase recalls Michael Porter’s book on The Competitive Advantage of Nations, as it was intended to. Porter asked, as we ask, why does one country do better in industry A and another in industry B? And why do some do better overall? But we refer to technological advantage.

Technological innovation is one of the driving forces of modern capitalism, and arguably the main one. We do not mean by this that those who develop or first introduce a new technology are necessarily those who dominate the economy. The race may go not to the technologically strongest, but to those with the sharpest commercial nose, or the best organised to exploit the new technology. Google did not invent or introduce the search engine but they thought of a refinement that would help it to serve the searcher better. Dell have done little to make computers better, but they were the first to introduce the techniques of e-business effectively for selling them and (starting from the sale) organising the supply chain. Both firms needed to master one or more novel areas of information and communication technology (ICT) in order to introduce their ‘commercial’ or ‘organisational’ innovations. For us, that is technological enough.

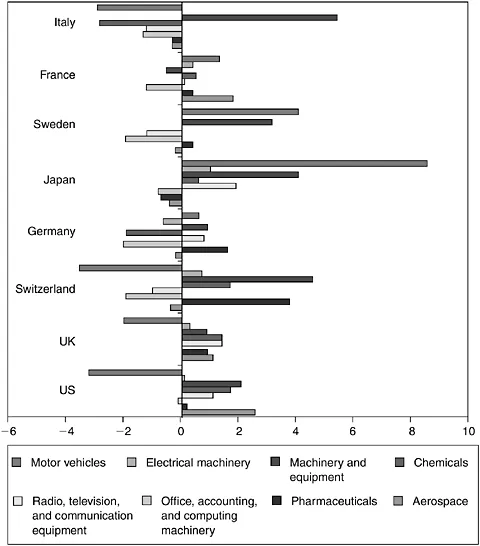

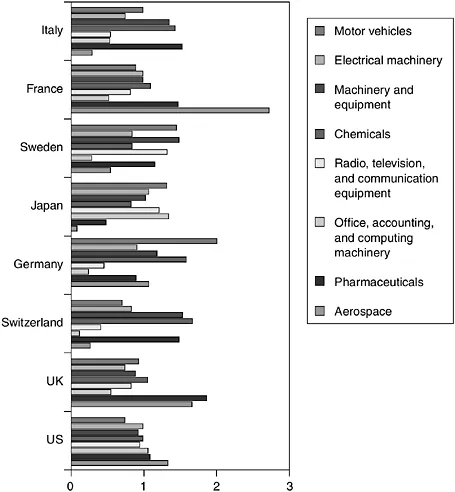

So our measures of technological advantage will not be only the production of new technology, as measured (very imperfectly) by rates of patenting. We shall also look at countries’ levels of production, and their trade balances, in sectors which can be defined as technologically demanding. The pattern of specialisation as shown by trade balances (as percentage of sector output: Figure 1.1) is broadly the same as that shown by relative patenting rates (otherwise known as Revealed Technological Advantage – Figure 1.2); that is, if a country has a trade surplus in sector X, then (out of all the patents taken out from that country) the proportion of them relating to sector X is likely to be relatively high compared to other countries. (For definitions of these measures see Statistical Appendix.) Thus, on both measures Japan and the United States are very strong in various areas of ICT hardware; Germany and Japan lead in motor vehicles; Germany, Japan and Italy lead in non-electrical machinery; Germany leads in chemicals. In a few rather ‘globalised’ industries this is not the case. In pharmaceuticals the US is strong on relative patenting but not on trade performance. This does not mean that patenting is a poor indicator of technological prowess in pharmaceuticals or that technological strength does not lead to commercial success there: it shows mainly that US firms often find it convenient to supply the huge US market with medicines they manufacture elsewhere.

Figure 1.1 Manufacturing trade balance (2001) percentage of output (source: OECD (2003a)).

Figure 1.2 Revealed technological advantage (1990–1999) (source: authors’ calculations on www.nber.org/patents (see Statistical Appendix)).

But are countries, or nations, the right level to consider technological advantage at? Do countries innovate? No, the main unit that can be said to innovate in a capitalist economy, is the firm. Still, firms are not isolated units: they compete and cooperate with others, and they have connections with other institutions of various kinds. Their interactions are particularly important in innovation, since innovation revolves around learning, and learning, as argued by Bengt-Åke Lundvall (1992: 1), ‘is predominantly an interactive and therefore socially embedded process which cannot be understood without taking into consideration its institutional and cultural context’. We have then to consider systems of innovation.

The first problem is where to set the boundaries of those systems. The early writings on systems of innovation were on national systems of innovation. The first book on the subject was Christopher Freeman’s (1987) on Japan, although Freeman gracefully conceded first use of the term to Lundvall.1 There were two key early edited works on national systems: Lundvall’s (1992) National Systems of Innovation: Towards a Theory of Innovation and Interactive Learning and Richard Nelson’s (1993) National Systems of Innovation: A Comparative Study. Even in a globalising world economy, there are factors that vary more among countries than within them—conditioning factors like consumer tastes; supportive factors like educational systems and research institutions. The interactions that are key to innovation—cooperation between firms and research institutions, collaborations among firms, rivalry and imitation among them—take place more frequently and intensely where geographical and cultural distances are short. And the national state even now can play an important role in the direction and rhythm of technological innovation (Niosi et al. 1993; Patel and Pavitt 1994; Freeman 1995; Edquist 1997).

Other authors place a major emphasis on regional systems of innovation, where regions might cross national borders or be part of a wider national system. For example Braczyk et al. (1998) trace the history and the structural characteristics of 14 regional systems of innovation. Useful as this work is, most would accept it as something of a supplement to that on national systems.

Both these approaches are geographical in the definition of space. The alternative is to divide the world economy by type of activity. That can be done in two different planes, vertical (following chains of production which connect producers to users), and horizontal (looking at a particular sector such as pharmaceuticals or steel). There are accordingly two competing approaches. The Technological Systems of Innovation approach (Carlsson and Stankiewicz 1991) emphasises cooperative relationships, many of which are in the vertical plane of interaction. Sectoral Innovation Systems, on the other hand ‘focuses on competitive relationships among firms by explicitly considering the role of selection environment’ (Breschi and Malerba 1997: 131). In other words, competition among the firms in a sector helps to determine which innovation emerges victorious. The other firms with which the firm relates—cooperatively as well as competitively—may well of course be foreign, and in a globalising world a sectoral innovation system will certainly extend across borders, as an ever-increasing number of firms do. We shall draw on the insights of both these approaches from time to time, particularly in Chapter 2.

Yet there is still something rather national about firms, most of them at least, and some of the most national aspects of firms, we shall argue, are connected to their finance and corporate governance. Finance and corporate governance (as the reader will be expecting us to insist) are important, and they are closely connected. Firms are organisations set up with the primary purpose (normally), and requirement (universally), of making profit. Firms must raise, use and reproduce capital in order to come into being, survive and grow: so the question of finance is central to a firm’s being, not a mere necessary inconvenience as it might be for a university or a government. Accordingly, those whose capital is most at risk in it—the shareholders—have the first (although perhaps not the only) claim to power over it. One cannot expect to understand firms’ behaviour in any area without understanding their finance and corporate governance.

In other words: in capitalism, capital and capitalists count. One might therefore expect the literature on technological innovation to give a central place to finance and corporate governance. It did so once. The founding father of the eco-nomics of technological innovation, Joseph Schumpeter, recognised the importance of finance and corporate governance. Innovation was usually expensive: ‘major innovations and also many minor ones entail construction of New Plant (and equipment) – or the rebuilding of old plant—requiring non-negligible time and outlay’ (Schumpeter 1939: 68). In his early work he saw these ‘new combi-nations’ as generally introduced by firms founded for the purpose—by entrepreneurs who were ‘new men’ not established in business (Schumpeter 1911/1996). Such innovators required external finance. Later, influenced by developments in US business, Schumpeter (1942) saw the main driver of innovation as the ‘perfectly bureaucratized giant industrial unit’, reinvesting profits into a routinised innovation process. Thus, for Schumpeter Mark I, financial institutions decided who should be given the resources to innovate: ‘[the banker] authorises people, in the name of society as it were, to form [“new combinations”]’ (Schumpeter 1911/1996: 74); for Schumpeter Mark II, the key decisions on resource allocation were part of the corporate governance of large firms.

After Schumpeter, the literature on innovation seems mysteriously to have fallen almost silent on matters of finance and governance. By way of example, we conducted a brief survey of 400 articles on innovation, between May 1998 and October 2003, and found only seven which gave any prominence (i.e. a mention in the abstract) to questions of finance or corporate governance.2 There are distinguished exceptions to this neglect. Lundvall’s 1992 book on NSI contained a chapter (by Jesper Christensen) on the role of finance. There is the work of Lazonick and O’Sullivan which we shall discuss later. And Keith Pavitt in the decade before his untimely death in 2003 looked more than once at the role of finance and corporate governance in national systems of innovation (Pavitt 1999). He argued, as we shall, that alongside national systems of innovation, and interacting with them, there are national systems of finance and corporate governance, and that the manner and outcome of innovation has been decidedly different between the US and UK on one hand and Japan and Germany on the other, because of radical differences in their systems of finance and corporate governance (Tidd et al. 2001: 93).

1.2 How can one classify and assess national systems of finance and corporate governance?

In parallel to, but quite separate from, the work done on national systems of innovation, there is now a large body of work on national systems of finance and/or corporate governance. It defines categories, assigns countries to them, and in a general way evaluates them.

At one time the most popular distinction was between stock exchange-based and bank-based (or market-oriented and bank-oriented) financial systems (Zysman 1983; Levine 1997, 2002; Allen and Gale 2000). The attraction was that this classification appeared to combine categories of corporate financing, equity ownership, and corporate control: thus, bank-oriented systems were for long believed to exhibit high levels of bank finance and of equity holdings by banks, leading to close and long-term relations between banks and firms and active governance by the banks. Few countries however display all these features. In one ‘bank-oriented’ economy, Germany for example, bank financing has been rather low (Edwards and Fischer 1994). Another major economy, Italy, fits poorly into either category (Tylecote and Visintin 2002).

Categorisation by ownership and control has been found more robust and useful. Franks and Mayer (1997) coined the terms ‘insider system’ and ‘outsider system’ to denote, respectively,

- economies with highly concentrated equity ownership, where larger blocks were generally held with control in mind (‘control-oriented systems’ in Berglöf 1997)

- economies with low equity concentration, where even the larger shareholders were generally uninterested in control (Berglöf’s ‘arms-length systems’).

See Table 1.1. The ‘outsider’ category corresponds well with the ‘stock exchange-based’ category above. The ‘insider’ systems comfortably include all the (allegedly) bank-oriented systems, but within them banks, where active, are merely one category of insider—family owners, government, and cross-holding firms are others. LaPorta et al. (1999) and Barca and Becht (2001) placed virtually all the non-English-speaking economies in the insider category, and the English-speaking economies in the outsider category. (We shall see later that the United States’ place is more arguable than most.)

It is by now well established that each type of corporate governance system has its advantages. When a number of economies with insider systems (such as Germany and Japan) seemed highly successful, in the 1980s, economists naturally noticed their strong points. Stiglitz (1988), Shleifer and Vishny (1986), and Huddart (1983) pointed out that concentration of ownership, such as insider systems show, provides strong incentives for active corporate governance. In the 1990, as the flaws of insider systems became more apparent in practice, and the US economy made a come-back, the theorists became more conscious of the arguments against them. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) and LaPorta et al. (1999) argued that the exercise of power by dominant shareholders can be at the expense of minority investors and, in consequence, can limit the availability of external capital. Franks and Mayer (1997) were conscious of the advantages of both types of system. They argued that large ‘blockholders’ can commit to long-term cooperative relationships with other stakeholders (such as employees, suppliers and customers); which may be an advantage where such relationships are needed, but a disadvantage where changes like the adoption of new technologies are resisted by such stakeholders. Mayer (2002) added another point in favour of the outsider system: financial institutions that diversify their portfolios of assets, with only small stakes in any one firm, can take a relaxed approach to high-risk investment. ‘Insiders’ may have too many eggs in one basket to do so.

Table 1.1 Types of corporate governance and financial system

If each type of system has its advantages, each will presumably tend to specialise in sectors in which its advantages are valuable and its disadvantages do little damage; and avoid sectors where the converse applies. A range of work has been done to explore this general proposition. Most of it gives more attention to the characterisation of the financial/corporate governance system than to that of the sectors examined. Thus, the one sectoral characteristic with which Rajan and Zingales (1998) and Cetorelli and Gambera (2001) are concerned is dependence on external finance. Carlin and Mayer (2003) go deeper: they look at industry measures of external equity financing, bank financing, and skill levels.

The insider–outsider distinction fits well into still wider frameworks, developed mainly by political scientists and sociologists, distinguishing ‘national business systems’ (Whitley 1999, 2002, 2003) or ‘varieties of capital-ism’ (Hall and Soskice 2001). We discuss this literature in some detail in Chapter 3; we shall only refer here to Hall and Soskice’s work. In brief, capitalism is seen as coming in two main varieties:

- economies in which the market is allowed to structure economic relationships,

- economies which are to a large extent coordinated through non-market relationships.

The first are called Liberal Market Economies (LMEs), the second, Coordinated Market Economies (CMEs), of which the main category is Business-Coordinated. Neatly, the LMEs (led by the US and the UK) have ‘outsider’ corporate governance (CG) systems, and the CMEs (of which the leading business-coordinated ones are Germany and Japan) have ‘insider’ CG systems. Neatly again, the explanation and predictions of ‘varieties of capitalism’ are generally quite consistent with those of the financial and corporate governance economists. The LMEs, driven by the market, excel in industries that involve ‘radical’ technological change; the CMEs, in which market forces are restrained, excel where ‘incremental’ change predominates. (Rajan and Zingales et al. would agree, because the former seem likely to require more R&D, thus more risk capital, thus more equity financing, which the outsider systems are seen as better at providing.) Hall and Soskice (H&S) compare the US and Germany, using data on patenting, and duly find that the US is generally more specialised in sectors they classify as ‘radically-inno-vative’, Germany in ‘incrementally-innovative’ ones. The sceptic Mark Taylor (2004) reviewed their work. First, he cleared them of the natural suspicion that sectors had been classified to suit the argument. He used the extent to which patents in a sector had, on average, been cited in subsequent patent applications as the criterion of ‘radicalness’, and broadly agreed with H&S’s classification. Second, he repeated their tests, first for the US and Germany, and then for LMEs compared with (business-coordinated) CMEs. It was for the expanded data set that the predictions failed—or rather, they depended totally on the inclusion of the US as an LME. Whatever the other LMEs have in common with the US—besides speaking English—it does not seem to be anything that makes for radical innovation. Likewise, on the CME side, Japan stood out, inconveniently, as a radical innovator, next after the US.

There is, in short, something about international specialisation—or, if you like, the technological advantage of nations—which remains to be explained, and it seems reasonable to look for a large part of the explanation in finance and corporate governance, broadly defined. None of the studies discussed started from a systematic analysis of the specific problems of financing and governing innovation and technological change. We shall now offer one.

1.3 Financing and controlling technological change: the challenges

The problems of financing and controlling technological change are related to the difficulties of analysing it. These are severe. Technology is a factor of production which, from the point of view of conventional neoclassical economics, misbehaves utterly. With the other main factors, land, labour and capital (physical or financial), the more is used the less is left. The reverse applies with technology, since it is essentially knowledge, the fruit of learning, and one learns by doing and by using. Frameworks of thought which have been developed to cope with the allocation of scarce resources, do not, therefore, apply to technology (Arrow 1962b; Stiglitz 1988). The other factors, moreover, are in every sense of the word visible: the quantities at a firm’s disposal can be measured and valued fairly reliably and accurately. Technology cannot be. Even codified knowledge, such as one finds in a formula or a blueprint, is hard to value, and much knowledge may not be codifiable; or firms may choose not to codify it: they may keep it tacit. The technological capability of a firm in practice is based on a complex and changing amalgam of codified and tacit knowledge, of intellectual and human capital (Teece et al. 1998). Moreover the monetary value of this capability—the profit that can be derived from it—depends crucially on its scarcity, which given the nature of technology is essentially artificial. Other firms must be prevented from getting it, by means which will usually involve a degree of secrecy. This reduces visibility even more.

The difficulties of valuing technological capability at a point in time—the valuation of technology as a stock – are great. Greater still may be the difficulties of valuing the resources invested in increased technolo...