1 Strategic and organizational challenges in European banking

Jordi Canals

In the early 1990s, European banks seemed to be in big trouble. The creation of the European Single Market in 1992, the collapse of the European Monetary System, the economic slowdown, the deregulation in financial markets and the emergence of new competitors were factors that created a sense of uncertainty – in some cases, even panic – among many European banks. However, most banks have survived, banking restructuring has been implemented in several countries and most banks are in a stronger position than in the early 1990s.

Many European banks have reinvented themselves by redefining their strategy, designing new organizational forms, launching innovative services and entering into new businesses. We have also seen in Europe the emergence of new universal banks, with a strong diversification strategy away from traditional retail banking, like Deutsche Bank or HSBC, and the creation of stronger regional banks, like Barclays, BBVA or Santander Group.

Nevertheless, the future of European banking looks uncertain. The implementation of the European single market in financial services is still far from being completed, which means that, in some segments of the financial services industry, national markets are still isolated, fragmented and somehow protected from external competitors.

Although the competitive positioning of many European banks has improved over the past few years, their comparison with the financial performance of US banks does not look particularly good. US banks, on average, are more efficient and profitable in using capital than European banks. On top of this, their market value is not only bigger, but also price–earning ratios are higher in US banking. One may argue that because European banks are not very profitable, US banks will not want to increase their business or acquire banks in Europe. But the right argument may be the opposite: precisely because many European banks underperform US banks, there is room for efficiency gains in this industry if better managed and financially stronger banks – in this case, US banks – take over less efficient ones.

The banking system depends very heavily on the state of the economy. With economic prospects in Europe so gloomy and no perspectives of acceleration in the growth rate, banks may have a hard time in generating revenue growth over the next few years. Moreover, Japanese banks seem to be back and we will see in the near future the emergence of banking giants in China. Certainly, scale is not the key factor for long-term survival in banking, but many European banks may be in the brink of being absorbed, unless they think about consolidation and, more important, change the way of running the business which today has become somehow obsolete.

Retail banking in several European countries is still organized the old way (Belaisch et al., 2001), with a heavy cost structure, not very intense price competition, slow innovation and poor customer service. In many ways, European banking does have the same competitive shape as some other European industries about ten years ago. The difference is that the pace of change in banking has been slower than in other industries. Regulation mixed up with political interference and the slow process of implementing the European single market are important explanations for the slow transformation of banking in Europe. But many US and a few European banks have been changing very quickly (see Canals, 2003), showing a possible way out. It seems clear that efficiency will drive the worst performers out of the market.

This paper discusses some strategic and organizational challenges that European banks are facing today. It is structured as follows: we will offer first an overview of some features of the European banking industry; next, we will analyse some major challenges that European banks will face in the next few years: closing the performance gap with US banks, fostering strategic renewal, managing organizational complexity and improving corporate governance.

1.1 Banking: the European landscape

1.1.1 Profitability

Table 1.1 offers an overview of the evolution of net interest margins between 1999 and 2003 for the United States, Japan and some key European countries. Financial margins have fallen since 1999 in all the countries considered. The US banking system still outperforms the rest of countries by far. In Europe, only Spain gets close to the US banking system. France and Germany are left behind and seem unable to offer products innovative enough to maintain the financial margin.

Table 1.1 Banks’ profitability as a percentage of total average assets (net interest margin %)

The profitability measured on average assets has also declined in all countries except in Spain, as shown in Table 1.2. Nevertheless, the US banking system shows a return on assets far above any other country. Spain and the United Kingdom, the next countries after the United States, show a return on assets 40% smaller than US banks. The case of German and Japanese banks is really bad, although Japanese banks seem to be slowly recovering.

The efficiency ratio – or cost-income ratio (CI) – is another way of looking at the efficiency of the banking industry. Table 1.3 shows the change in this ratio between 2003 and 1998 for the top twenty banks in terms of market capitalization at the end of 2003. US banks are the most efficient ones, with ratios of about 50% or less. The superior performance of US banks has to do not only with their cost efficiency, but also with their ability to generate higher absolute revenue, stronger than the ability of European banks.

Table 1.2 Banks’profitability as a percentage of total average assets (pre-tax profits %)

Table 1.3 Top 20 world banks cost/income ratio (%)

Market valuation highlights how different US and European banks perform and the gap in scale that is dividing banks on both sides of the Atlantic. Table 1.4 shows the top twenty banks in the world in terms of market capitalization (December 2003), with Citigroup far away from the rest of banks and only one European bank, HSBC, getting close to the second US bank, Bank of America.

Table 1.4 Top 20 world banks market capitalization (December 2003, $M)

Table 1.5 Market concentration (%)a

Moreover, the potential for market concentration in the United States is still high, which means that the average scale of top banks in the United States can become bigger. Table 1.5 shows the market concentration index for seven countries in 1997 and 2003. The increase in the concentration levels is generalized. But Germany, the United States and Italy are the laggards. It is more difficult to see more European banks buying US banks than US banks entering more aggressively into Europe. Both trends – further consolidation in the United States and the opening up of European banking to the rest of the world – are good opportunities for US banks and a threat for European banks.

1.1.2 Growth and diversification

The average scale of banks has substantially increased over the past years in Europe and the United States (see Berger et al., 1999). Table 1.6 shows the top twenty banks in terms of total assets in 2003 and their size in 1999. This increase is remarkable. Banking growth has been driven mainly by mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and the diversification process of banks away from retail activities to corporate banking, asset management, capital markets transactions and advisory services.

The increasing importance of financial markets in the Western world has attracted many retail banks to capital markets, setting up new advisory, investment banking, trading and research units or acquiring other firms. The anecdotal evidence of this trend is clear. Deustche Bank acquired Bankers Trust; Dresdner Bank acquired Kleinwort Bentson; Citigroup acquired Schroders; ING acquired Barings; Crédit Suisse acquired Donaldson Lufkin and Jenrette; UBS and SBC merged; Chase Manhattan acquired JP Morgan. The evolution of non-interest income as a percentage of gross income in the European Union (EU) is clear. In the 1980s, this ratio was less than 25% in most EU countries; in 2000, it was about 40% in the Eurozone countries (Canals, 2003). This ratio is not the only indicator of diversification, but shows in a simple way how much banks are going away from traditional intermediation and interest-based transactions to fees-based financial transactions. This means that banks are not only changing the nature of their activities as financial intermediaries, but also the type of capability they need to develop to bolster their competitive advantage.

Table 1.6 Top 20 world banks total assets ($M)

Moreover, this diversification process of many European banks is not only a reaction against low revenue growth in some traditional banking activities, but also the belief that the universal banking model, with a holding company and several business units competing in different segments of the financial services industry, is the pathway to the future.

Universal banks seem to show some advantages over more focused banks (see Saunders and Walter, 1994; Canals, 1997). The first is the potential to exploit linkages among the bank’s business units and, in particular, the advantage of cross-selling of financial services. The opportunities for cross-selling seem to be important in retail banking, asset management, investment funds and insurance. Nevertheless, the volume of cross-selling does not increase as quickly as some banks would wish, for a variety of reasons. First, a bank may not offer the best set of financial services and its competitive advantage in cross-selling may be weak. Second, rivalry in each segment makes competition very tough for universal banks, and specialists may be more efficient. Third, the universal banks’ internal organization does not always create an efficient coordination between the business units selling different types of financial services from the clients’ point of view. Fourth, the distribution system of universal banks has become increasingly specialized and segmented; the creation of special branches for high-income individuals or special networks for serving the corporate market reflect this trend. This means that fragmentation of distribution channels may play against the integration of financial services that cross selling requires.

The second potential advantage for universal banks is the diversification of the sources of earnings and the prevention of the risk of substitution. This risk consists of the threat of innovation that comes from new financial services or alternative distribution channels. The emergence of new products such as investment funds or new distribution channels, such as Internet banking, makes this threat evident. Some banks’ senior managers also argue that the diversification of earnings may increase earnings’ stability. This may be true only in those activities in which earnings tend to be stable themselves – for example, they come from recurrent activities – but not in the cases of those activities – like capital markets – which are not. However, from a strategic point of view, what really reduces the risk of substitution is innovation. In this respect, universal banks do not have in fact a clear advantage over specialized banks.

Universal banks may enjoy another advantage: the offer of ‘a one-stop shop’ by becoming exclusive providers of a wide range of financial services to individuals, families and firms. Firms may be edging towards dealing with a smaller number of banks. However, it is less obvious that a single bank can be superior to others in providing all of the financial services that companies might require. In Europe, some universal banks with a strong corporate banking presence have a leading role in lending. However, it is more difficult for them to compete with US investment banks in advisory functions, mergers or acquisitions. Their problem lies not so much in the size of the market, as in the fact that US banks have an extensive experience and developed unique capabilities in deal-making.

However appealing the advantages of universal banks might be, the problems and challenges that they involve are also relevant. These are extremely complex organizations from a managerial perspective, with specific coordination and compensations problems stemming from the fact that they are the umbrella under which sometimes very different business units operate. Universal banks also generate conflicts of interests, with different business units – investment banking, lending, advisory services, etc. – fighting for their sources of revenue.

From a profitability viewpoint, there is no evidence that universal banks – diversified financial services firms – are more profitable than focused banks. On the contrary, profitable banks may be big and small ones, depending also on the industry conditions in each country and, eventually, on the quality of management of each bank.

Nevertheless, even if the evidence does not fully support the vision of universal banks, there is no doubt that they are shaping financial institutions today in the European landscape.

1.2 European banks: main challenges and risks

Taking into account the competitive and financial position of European banks in the beginning of the 1990s, their evolution over the past ten years has been a reasonable success for many of them. Nevertheless, this industry is clouded by internal challenges and competitive threats. It is difficult to predict which specific pathway its evolution will follow, but it is true that this industry has not gone through a strong restructuring process as other European industries, and the room for efficiency improvement is still significant.

In this section, we will discuss four major challenges that European banks will have to tackle over the next few years, because their survival depends very much on their success in overcoming more intense competition for clients and markets: closing the performance gap with US banks, fostering strategic renewal, managing organization complexity and improving corporate governance.

1.2.1 Closing the performance gap

As seen in the previous section, European banks’ profitability has declined over the past few years – see Tables 1.1 and 1.2 – with some notable exceptions. And US banks are, by far, still more profitable than European banks. This generates a performance gap, an asymmetry between banks on both sides of the Atlantic as highlighted earlier. European banks have to tackle the challenge of closing this gap as they want to make sure that they have control of their destiny in their hands.

A deeper explanation for financial performance in European banking is the lack of economic growth and the low potential for growth revenue in many areas of financial services. Slow growth plays into the hands of cost cutting, which becomes the undisputable tool to improve performance in Europe, since European banking has still higher fixed costs and CI ratios. However important it may be, cost cutting is neither a guarantee of long-term survival and success, nor a signal of revitalizing banks’ strategies which is what many banks actually need.

Investment in technology has declined over the past three years, but it will come back in banking and will give those banks that invest smartly in technology a more effective weapon to lower operational costs. Unfortunately, many banks have turned their back on technology after the bubble burst in 2001–2002, but there are many successful examples of how technology can help manage banking operations more efficiently.

A direct outcome of the lower banking profitability in Europe is that the European banks’ market value is smaller than that of US banks. This lower valuation, in combination with the sheer size of some US banks, transforms them into potential and powerful bidders in European banking. European banks will not be in control of their future unless they can reduce this performance gap.

What are the generic options for European banks in order to close this gap? Three generic approaches have been followed. The first is looking for more efficiency through cost restructuring (Berger and Mester, 1997). The second is downsizing and assets sell-off of those units, which the current management cannot run well and that absorb too much capital in an inefficient way. Finally, a restructuring of the portfolio that include both asset disposal and investment in new business.

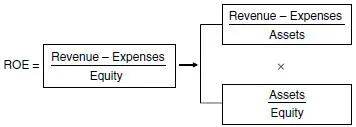

These generic approaches could be useful in some instances, but do not resolve the underlying problems of European banks. The reason is simple. The return on assets of any company is the difference between revenue and expenses, over total assets. The problem with the three approaches described previously is that they may be good at cutting costs and refocusing banks away from marginal business, but not good enough for the real challenge that banks have to go through in order to improve long-term performance.

Figure 1.1 shows the arguments. Banks can reduce expenses and improve their return on equity; or sell assets, in order to improve their rate of return on assets. Nevertheless, these are not sustainable policies in the long term, since there is a limit to cutting expenses or how far a bank can proceed with asset disposal. Unless banks make an effort to boost revenue growth in the long term and use capital more efficiently, it will be impossible to close the performance gap that separates US banks from European banks. The growth challenge is the next issue to be discussed.

Figure 1.1 Return on equity (ROE).

1.2.2 Strategic renewal

Concern about banks’ market value has focused the attention of senior managers inside and outside the banking industry. Nevertheless, this approach is essentially flawed, since the share price should be the outcome, not the driver, of a good business strategy. There is a sense of despair about the market value of some European banks, with a significant asset size, in particular, when they compare their valuation vis-à-vis US banks’ valuations. However, this uneasiness is useless because there is not the same sense of urgency about rethinking banking strategies, or considering the deeper, underlying factors that drive market value in the long term. Rediscovering the meaning of strategy in banking is critical if banks want to focus on long-term growth.

And the banking landscape for growth will become more difficult in the following years. Revenues in some traditional business segments are flat. Rivalry will become more intense, with savings banks and other financial services firms different from banks offering new, innovative savings products and advisory services. Many indicators seem to suggest that customers in banking are not particularly loyal to their banks and switching costs are more of an unwanted chain around customers than the outcome of excellent bank service. Finally, in Europe economic growth has been disappointing over the past decade and, unfortunately, it does not seem that its prospects may change in the near future. In this landscape, financial services will not grow dramatically unless banks offer some innovative services.

Strategic renewal in banking includes s...