- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Throughout the history of social thought, there has been a constant battle over the true nature of society, and the best way to understand and explain it. This volume covers the development of methodological individualism, including the individualist theory of society from Greek antiquity to modern social science. It is a comprehensive and systematic treatment of methodological individualism in all its manifestations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Methodological Individualism by Lars Udehn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & Theory1 Introduction

There has been in the history of social thought a constant battle over the true nature of society and about the best way to understand and explain it. A major divide goes between those who see society as an aggregate, collection, or complex of individuals and those who see society as some kind of ordered whole and/or unitary collective. The former try to explain social phenomena in terms of individuals and their interaction, while the latter maintain that this is not possible without essential reference to the social wholes of which they are part and/or the collectives to which they belong.1 The opposition between these conceptions of society was inherited by the social sciences and divided them in two conflicting camps. With the emergence of the social sciences, however, the metaphysical issue was increasingly turned into a methodological issue. As we shall see, this does not mean that the metaphysical issue disappeared, only that it receded into the background.

There have been many names used to designate the two camps and their respective doctrines. In the twentieth century two (or three) names have been selected as the most common. The battle has been increasingly waged in terms of methodological individualism, and its transmutations, versus methodological collectivism and/or holism. My interest, in this book, is in the former, but in order to understand one side, it is necessary to take a look also at the other side. Above all, it is necessary that there is a genuine divide separating the two doctrines, or else this book would be very much ado about nothing.

There are those who see, in this issue, the most fundamental and most important problem of the social sciences: that of the relation between individual and society. According to others, however, individualists and holists are engaged in a sham battle.2 I believe the first view is more correct. Anyone the least acquainted with the social sciences, knows that it matters which view you adopt in this matter. Methodological collectivists and holists do tend to ask different questions and provide different answers than do methodological individualists. There are important differences also within the two camps, but this is another matter. I also find it hard and a little bit odd to believe that the best minds in the history of social thought should really have engaged, and with so much energy, in something which turns out to be a sham battle. Didn’t they notice?

When I first started working on the topic of methodological individualism, I was often told that the debate about it was over. Several sociologists tried to persuade me that arguments against methodological individualism advanced by Steven Lukes and others are so strong as to render methodological individualism a mere curiosity, or at least harmless. The main point of Lukes was that it is vain to discuss methodological individualism without making clear what conception of ‘individuals’ you are using (Lukes, 1968; see also Burman, 1979). His argument was addressed in part to the methodological individualist, J.W.N Watkins, who had argued that methodological individualism is, or follows, from the ontological ‘truism’ that ‘[a]ll social phenomena are, directly or indirectly, human creations’ (Watkins, 1952a: 28).

Today, we know that the debate about methodological individualists was not over. With the recent upsurge of rational choice, a new wave of methodological individualism has swept the social sciences. One of the most influential advocates of this approach, Jon Elster (1986b: 66; 1989b: 13),3 has recently repeated Watkins’s claim that methodological individualism is trivially true, but since it is impossible for a methodology to be at all true, I suppose that Elster really means metaphysical, or ontological, individualism.4 J.W.N. Watkins was more correct on this point, at least, since he recognised that his truism is an ontological thesis rather than a methodological rule. But, as he later himself admitted (1952b: 186f), he was nevertheless wrong to assume that the latter follows from the former. Even if ontological individualism is trivially true, it does not follow that methodological individualism is the only, or even the best, way to explain all social phenomena (Lukes, 1968; Kinkaid, 1997: 4, 16f). As Ernest Gellner (1956: 176) put it some time ago, with respect to history: ‘History is about chaps. It does not follow that its explanations are always in terms of chaps’. Today, it is fairly common to accept ontological individualism, but deny methodological individualism. 5

I am not going to argue against ontological individualism, here, but I deny that it is trivially true. It is only if stated in a trivial enough way, that ontological individualism is true, but this says little, or nothing, about the real issues involved in the debate about it (cf. Miller, 1978; 1987: 115). If, for instance, methodological individualism is only intended to deny that society is literally an organism endowed with a mind, or consciousness, which exists apart from the minds of individuals, then, it is of course true, but as Miller points out, even the archholist, Hegel, maintained that the world spirit is manifested in the actions of individual human beings and nowhere else.6 Also, to suggest that the ‘truth’ of methodological individualism is secured by the fact that social wholes are made up of individuals and their relations to one another is to beg the fundamentally important questions: ‘What is an individual?’ and ‘What is a social relation?’7

The issue between methodological individualists and their critics, then, is genuine, but this does not mean that the debate has always been about the real issues involved. Far from it. There has been too much confusion surrounding the meaning and implications of the two positions, for a really fruitful debate to take place. This sad fact, has, no doubt, contributed to create the impression of a sham battle. To an astonishing degree, the disputants have argued at cross- purposes, and without a manifest intention to understand the opposite point of view. There has been a marked tendency among representatives of both sides to misinterpret and misrepresent the ideas and arguments put forward by the other side.

The reason for this is, probably, that the issue of methodological individualism versus collectivism and holism is felt to be important, not only for purely scientific, but for extra-scientific reasons as well (cf. Kinkaid, 1997: 2ff). First of all, it seems to be inextricably mixed up with some of people’s most entrenched, and most strongly-held beliefs about human nature and society. Second, these beliefs seem to be closely linked to their moral and political convictions. Third, there is clearly a connection with fundamental beliefs about science and its growth. Finally, there is a more crass reason for social scientists to have strong opinions about methodological individualism. It seems to have territorial implications. Many social scientists, especially sociologists, have, no doubt, rejected methodological individualism, because they believed that it implies psychologism, or the reduction of sociology to psychology. If so, methodological individualism would rob sociologists of their discipline. For all these reasons, the debate between methodological individualists and their critics has been more confused than usual in social science and philosophy.

It may be maintained – and sometimes I have been inclined to think so myself – that the debate between methodological individualists and methodological holists concerns one of those eternal issues which will never be settled by social science, philosophy, or by any form of argument. If so, it is, of course, mere waste of energy to write a book about it. Now, obviously, this is not what I believe. While, I still think that the issue between individualists and holists might never be finally settled, once and for all, I do believe that it is possible to make some progress.

The aim of this study is to bring some clarity about the meaning of one side of the divide: methodological individualism.8 This is much needed, since, as David-Hillel Ruben (1985: 132) has maintained: ‘methodological individualism has never been stated with enough clarity and precision to permit its proper evaluation’. Now, I do not cherish any illusions about what can be accomplished by way of remedy, but I do hope to be able to shed, at least, some light on this controversial doctrine. I will try to do so by writing the history of methodological individualism. As far as I can see, there is no other way to contribute to our understanding of a doctrine than by looking at the various statements and uses of it in the history of ideas; in this particular case, in social science and philosophy.

Since no doctrine can reasonably be interpreted as the sum total of all statements about it, at first I imposed two criteria of adequacy: Statements about methodological individualism must be consistent, and the doctrine stated must be significant. By the latter criterion, I mean that methodological individualism must be stated in such a way that it fits those social scientific theories and approaches which are generally considered individualistic.

While working with this book, I have decided to drop both criteria. The reason is that the idea of methodological individualism has developed in curious ways, and is hard to recognise these days. It would, of course, be possible to stick to the criterion of consistency and rule out what is not consistent with the original version of methodological individualism as being something else. When an increasing number of people begin to believe that this else is methodological individualism, however, this strategy becomes problematic. In this situation, I have decided to take a less essentialist approach and accept the development of new versions of methodological individualism, different from the original one, but, nevertheless, versions of methodological individualism. The criterion of significance is, of course, dependent upon that of consistency, but it is still possible to conceive of some social scientific theories as being paradigm cases of methodological individualism and other theories as being more or less individualistic, compared to these paradigmatic cases.

There are several possible ways of approaching the task I have set myself. The most obvious way to proceed is, probably, to scan the literature for explicit statements of the doctrine of methodological individualism. Another way is to concentrate on the uses of methodological individualism in social science and history. There might be other ways, as well, but these are the ways I have followed. In order to clarify and, perhaps, justify the second route, I make a distinction between methodological individualism as a principle, or programme, of social research, and methodological-individualism-in-use; social science that is in line with this principle, or programme, without being explicitly based upon it. It is, of course, possible to suggest, or accept, theories that comply with the strictures of methodological individualism, without being committed to, or even be aware of this principle, or programme. If we have to do with theories rather than particular explanations, it is possible to speak of ‘theoretical individualism’, and if it is a general theory, of the ‘individualistic theory of society’. When I use these expressions, in this book, I understand pieces of social science, which qualify as methodological-individualism-in-use.

This study, then, seeks the meaning of methodological individualism in the short history of this doctrine. Methodological individualism goes back to the nineteenth century, and the various attempts to lay the foundation of the social sciences. The individualist theory of society is much older, of course, but this is a topic I will treat in another book.9

How do I choose what to include in this history? Who are the main representatives of programmatic methodological individualism and which theories are paradigms of methodological-individualism-in-use? There is no certain way to decide these things and, in the end, you have to rely on previous knowledge and rules-of-thumb, as your main guides. A first rule I have tried to follow, is to concentrate on those social scientists and philosophers, who themselves are adherents of methodological individualism, to the exclusion of those who merely comment upon it, or criticise it. A second rule I have followed, is to pay most attention to those methodological individualists who are singled out as most important by the scientific and philosophical communities. ‘Most important’, in this case, means most cited in the literature. Equally, when it comes to methodological-individualism-in-use. I have presented those theories and approaches which are commonly cited as individualistic and actually there is more agreement on this than on the exact meaning of methodological individualism.

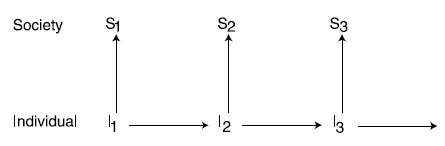

In order to illustrate the differences there are between various versions of methodological individualism, I am going to make use of some graphic representations (see Figure 1.1). More specifically, I will use a scheme I have borrowed from the philosopher Arthur Danto (1965a). As we shall see, many others have used similar schemes to represent the relations between individual and society, action and structure, or micro and macro. As I use Danto’s scheme there are two levels, representing the individual and society, respectively. The arrows represent the direction of explanation according to methodological individualism proper, or of causality in the case of ontological individualism.

Figure 1.1 A graphic representation of methodological individualism

Source: Adapted with modification from Danto (1965a: 269)

A word of warning should be voiced immediately against interpreting this simple scheme too literally. Individualists and collectivists usually understand both individual and society in different ways. To assume that we can talk about the individual and society in a neutral way is, therefore, an illusion (Lukes, 1968: 123ff; Archer, 1995: 34ff). If necessary qualifications are made, however, I think the Danto’s two-level scheme is a useful tool for making the differences between various versions of methodological individualism visible.

Two more clarifications need to be made before I get on to my real task. This study is all about the meaning of methodological individualism, and not at all about its merits, if any. This does not mean that I am, somehow, neutral in the debate between methodological individualism and its critics. I belong to the critics, even if I am far less critical of the recent, weak versions of methodological individualism than I am of the original, strong version. Even so, I have refrained from passing explicit judgement on methodological individualism in this work and I have tried, seriously, to give a fair account of its background, history and meaning. I hope that I have succeeded.

Finally, I am a sociologist, interested in the other social sciences and in philosophy, but, nevertheless, a dilettante, outside my own discipline. I have tried to understand the intricacies of economics and philosophy, in particular, and I hope I have succeeded reasonably well, but I may, of course, have failed in some respect. If so, I hope that my failure does not seriously damage the overall quality of this work.

2 Background

The individualist theory of society has a long history in Western thought. Since I will try to tell this history in another volume, I will not go into details here. My purpose in this chapter is merely to provide a brief background to the rise of the specifically methodological version of individualism. For this purpose, I will first present the two main versions of the individualist theory of society which preceded methodological individualism; the theory of the social contract and the theory of spontaneous order, as it took shape in Adam Smith’s idea of the market as an invisible hand. This idea laid the foundation of economics and it is often assumed that classical economics was not only the first social science, but also the first example of methodological individualism. I am going to argue below that, as such, it was not an altogether clearcut example, although I agree, of course, that it was more individualistic than the views of most of its critics. Classical economics was mainly a British phenomenon, but in Germany, and to a lesser degree in France, there was a massive reaction against the individualism of the Enlightenment, of utilitarianism and of classical economics. The main expression of this reaction is the cultural movement known as Romanticism, whose most significant manifestation in the human sciences is German historicism. In France there emerged a doctrine which shared some elements with both British and German thinking, namely the positivist sociology of Auguste Comte. Methodological individualism emerged, I believe, as an individualist counterreaction to the anti-individualist reaction of German historicism and the sociologism of positivist sociology. If this belief is correct, it becomes necessary to include the latter two intellectual currents as important parts in any account of the background of methodological individualism.

The social contract

The individualist theory of society goes back, as far as we know, to Greek Antiquity, where it was advanced, in particular, by the Sophists and by the Epicureans. The former invented the theory of the social contract and saw all social institutions as man-made conventions. The latter adopted the theory of the social contract and added to it an atomist metaphysics and a hedonist psychology.

The individualist theory of society disappeared with Antiquity and was replaced by a more holistic and collectivist view of society in the Middle Ages. It reappeared in the Renaissance and culminated with the Enlightenment. The most important figures are Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and John Locke (1632–1704), at least from an individualist point of view. Of these, I believe Hobbes is the most important as a representative of a theoretical, and perhaps also methodological, individualism, while Locke is more important as a representative of political individualism.

The point of departure of most theories of the social contract, and Hobbes’s theory is no exception, is the ‘state of nature’. In Hobbes’s version, the state of nature is characterised by a war of each individual against all other individuals.

In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no Account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continual feare, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish and short.

(Hobbes, [1651] 1968: 186).

The reason for this sad state of things is that there is no law and no commo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Background

- 3 Psychologism in early social science

- 4 Austrian methodological individualism

- 5 Society as subjectively meaningful interaction

- 6 Positivism in philosophy and social science

- 7 Popperian methodological individualism

- 8 Economics: The individualist science

- 9 The new institutional economics

- 10 Rational choice individualism

- 11 Why methodological individualism?

- 12 Methodological individualism restated

- Notes

- Bibliography