![]()

1 A financial sector to support development in low-income countries1

Stephany Griffith-Jones with Ewa Karwowski and Florence Dafe

Introduction

Designing a financial sector and its regulation, in a way that promotes development, provides a particularly challenging area for policy design and research. The policy challenges and research needs are very large, due partly to a major rethinking of the role, scale and structure of a desirable financial sector, as well as its regulation, in light of the major North Atlantic financial crisis. This crisis challenged the view that developed countries’ financial systems and their regulation should be emulated by developing countries, given that developed countries’ financial systems have been so problematic and so poorly regulated. Furthermore, it is important to understand the implications of the major international policy and analytical rethinking, including on regulation, for low-income countries (LICs) in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

The financial sectors of African LICs are still at an early stage of development so that lessons from the crisis could inform their financial sector development strategies. They have the advantage of latecomers. Moreover, their financial sectors, while generally still shallow, are experiencing fairly rapid growth. Combined with African countries’ existing vulnerabilities, such as limited regulatory capacity, and vulnerability to external shocks, this might pose risks to financial system stability. Despite the infrequent appearance of systemic banking crises on the African continent over the past decade (see below), fast credit growth in many economies – even if at comparatively low levels – calls for caution, signalling the need for strong, as well as countercyclical, regulation of African financial systems. For policy-makers and researchers, this poses the challenge of applying the lessons from the crisis in developed and previously in emerging countries to African LICs, while paying careful attention to the specific features of African financial systems.

There are also more traditional policy challenges and research gaps on financial sectors in LICs and their links to inclusive growth. To support growth, there are a range of functions that the financial sector must meet in African LICs, such as helping to mobilize sufficient savings; intermediating savings at low cost and long- as well as short-term maturities to investors and consumers; ensuring that savings are channelled to the most efficient investment opportunities; and helping companies and individuals manage risk. There are also large deficiencies in these areas originating from specific market failures and/or gaps. For example, there is a lack of sustainable lending at relatively low spreads, including with long maturities to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which is particularly constraining for growth in LICs.

This chapter presents two key areas for a policy, as well as a corresponding research agenda for the four case studies on finance and growth in SSA: 1) the desirable size and structure of the financial sector and 2) new challenges for financial regulation. Discussions in these two areas are important to advance understanding of the links between the financial sector and inclusive as well as sustainable growth, and any possible trade-offs.

Financial sector development and growth

Central bankers and financial regulators in African LICs have always faced major conceptual and institutional challenges in striking the right balance in their policy design to achieve the triple aims of financial stability, growth and equity.

These challenges acquired a new dimension in the light of numerous financial crises, initially in the developing world, but recently in developed countries. The latter led to a major re-evaluation of the role of the financial sector, its interactions with the real economy and the need for major reform of its regulation, especially in developed and emerging economies (see for example, Griffith-Jones et al., 2010, as well as IMF, 2012b). Among proposed regulatory reforms, Haldane and Madouros (2012) point in particular to the need to simplify regulation, which resonates very well with LICs.

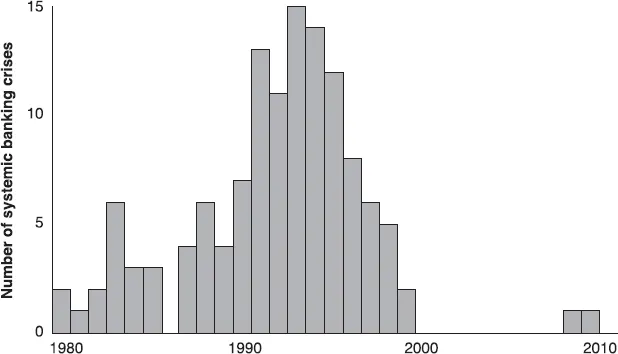

It is important to note that the number of banking crises on the African continent has overall been remarkably low over the past decade (2000–2010), potentially indicating increased resilience of African financial systems, particularly in comparison to the 1990s (see Figure 1.1).

In this context the Nigerian banking crisis, the only fairly large crisis in that period – discussed below – is seen by some as a “sporadic outlier” (Beck et al., 2011:3). There is, nevertheless, the danger that absence of recent crises can lead to policy-makers’ and regulators’ complacency (as well as that by the financial actors), which precisely could increase the risk of future crises. This phenomenon, known in the literature as “disaster myopia”, has in the past contributed to increased risk of crises in all other regions.

There has been relatively little research and policy analysis on the implications of the Global Financial Crisis for African countries and LICs more generally, with some valuable exceptions (see for example, Kasekende et al., 2011, and Murinde, 2012 for good analyses of regulatory issues in LICs). As African financial sectors are growing quite quickly, they may be more vulnerable to threats to their financial stability. This book, and the research that gave rise to it, attempts to contribute to help answer the question of how the need to ensure financial stability interacts with the need of a financial system in LICs that assures enough access to sustainable finance for the different sectors of the economy, including long-term finance to fund structural change, as well as different segments, such as SMEs and infrastructure.

Figure 1.1 Systemic banking crises in Africa, 1980–2010

Source: Laeven and Valencia, 2008 and 2012.

The key issues

There are two areas of issues for understanding the links between the financial sector and inclusive, as well as sustainable, growth: 1) what is the desirable size and structure of the financial sector in LICs?; and 2) what are the regulatory challenges to maximise the likelihood of achieving financial stability, whilst safeguarding inclusive and more sustainable growth?

Size and structure of the financial sector

At a broad level, what is the desirable size and structure of the financial sector in African countries, to maximise its ability to support the real economy? What are the desirable paths of development of the financial sector in Africa to help it maximise its contribution to growth, considering the features of African countries and lessons from recent crises?

The traditional positive link between deeper as well as larger financial sector and long-term growth, that started in the literature with Bagehot and Schumpeter, but then was reflected in quite a large part of the empirical literature, such as Levine (2005), is being increasingly challenged. Authors like Easterly et al. (2000) had already early on suggested that financial depth (measured by private credit to GDP ratio) reduces volatility of output up to a point, but beyond that, it actually increases output volatility. More recently, a number of papers are showing an inverse relation between size of financial sector and growth, especially beyond a certain level of financial development, which is estimated at around 80–100 per cent of private credit to GDP. Thus, Bank for International Settlements (BIS) economists based on empirical work reach the following conclusions, which challenge much of earlier writing:

First, as is the case with many things in life, with finance you can have too much of a good thing. That is, at low levels, a larger financial system goes hand in hand with higher productivity growth. But there comes a point – one that many advanced economies passed long ago – where more banking and more credit are associated with lower growth.

(Cecchetti and Kharroubi, 2012:1)

Secondly, looking at the impact of growth in the financial system – measured in employment or value added – on real growth, they find clear evidence that faster growth in finance is bad for aggregate real growth. This implies financial booms are bad for trend growth. Hence, macro-prudential or countercyclical regulation, discussed below, is important.

Finally, in their examination of industry-level data, they find that industries competing for resources with finance are particularly damaged by financial booms. Specifically, manufacturing sectors that are R&D-intensive suffer disproportionate reductions in productivity growth when finance increases.

Similarly, an IMF Discussion Paper (IMF, 2012a) suggests empirical explanations for the fact that large financial sectors may have negative effects on economic growth. It gives two possible reasons. The first has to do with increased probability of large economic crashes (Minsky, 1974; Kindleberger, 1978 and Rajan, 2005) and the second relates to potential misallocation of resources, even in good times (Tobin, 1984). De la Torre and Ize (2011) point out that “Too Much Finance” may be consistent with positive but decreasing returns of financial depth, which, at some point, become smaller than the cost of instability. It is interesting that the IMF Discussion paper (IMF, 2012a) results are robust to restricting the analysis to tranquil periods, confirming that the “Too Much Finance” result is not only due to financial crises and volatility, but also misallocation of resources.

It is also plausible that the relationship between financial depth and economic growth depends, at least in part, on whether lending is used to finance investment in productive assets or to feed speculative bubbles. Not only where credit serves to feed speculative bubbles – where excessive increases can actually be negative for growth – but also where it is used for consumption purposes as opposed to productive investment, the effect of financial depth on economic growth seems limited. Using data for 45 countries for the period 1994–2005, Beck et al. (2012) and Beck et al. (2011) show that enterprise credit is positively associated with economic growth but that there is no correlation between growth and household credit. Given that the share of bank lending to households increases with economic and financial development and household credit is often used for consumption purposes whereas enterprise credit is used for productive investment, the allocation of resources goes some way towards explaining the non-linear finance–growth relationship. In African countries, only a small share of bank lending goes to households. However, as financial sectors and economies grow, this will change, as has been the case in South Africa.

Rapidly growing credit to households – even though desirable and potentially welfare enhancing when strengthening reasonable levels of domestic demand and financial inclusion, in a sustainable way – might, however, cause financial instability, as well as harm poorer people, if not regulated prudently.

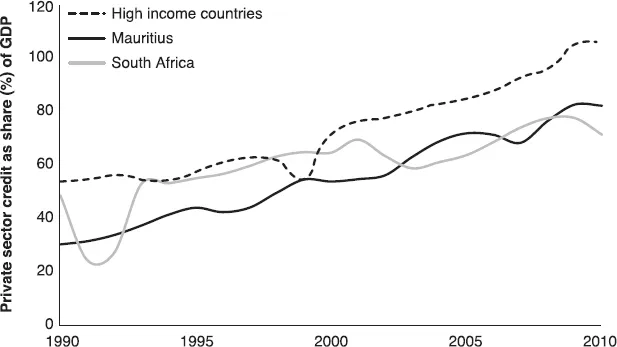

Excessive lending to the construction sector is another important source of financial instability, particularly when it creates a housing bubble. The two most advanced African economies – South Africa and Mauritius, both upper middle income countries – have recently experienced or are currently experiencing a construction boom. Both economies possess relatively deep financial markets with strong private domestic lending, including significant consumption credit extension. Figure 1.2 shows that private credit in high income economies was around 100 per cent of GDP on average in 2010 while it accounted for 70–80 per cent of GDP in Mauritius and South Africa.

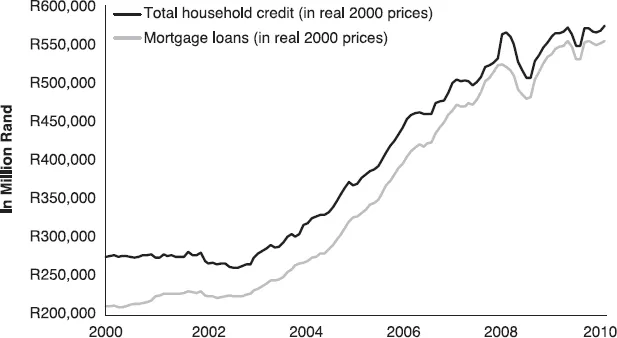

South Africa was the country in Africa which experienced the strongest real house price growth between 2004 and 2007, by far exceeding even the price growth in the booming residential property markets of the US and the UK. In South Africa the ratio of household to business credit is approximately 1:1. The large majority of household borrowing takes on the form of mortgage finance. During the early 2000s this led to an unprecedented housing boom in South Africa, as growth in housing loans was over 150 per cent in real terms between 2000 and 2010 (see Figure 1.3). This was largely absorbed by upper income South African households accounting for three-quarters of total household credit created during the period (DTI, 2010). In an attempt to reduce inflation, asset price increases and potential macro-economic over-heating, the South African Reserve Bank gradually initiated monetary tightening in June 2006, accelerating the rise in interest rates in the following year.

Figure 1.2 Private credit extension in African middle income countries compared to high income countries, 1990–2010

Source: The World Bank, 2013b.

Figure 1.3 South African private sector credit extension by purpose, 2000–2010

Source: SARB, 2013.

The subsequent economic slowdown in South Africa was to a large extent caused by measures to correct domestically accumulated economic and financial imbalances, while the Global Financial Crisis merely intensified the recession of 2008/09. The fact that credit and consumption-led growth was unsustainable in South Africa was illustrated in almost one million jobs shed in 2008/09, largely in low-skilled consumption-driven sectors. A positive aspect was that there was no banking crisis, perhaps because of the positive policy response from the economic authorities. However, as mortgage credit picks up, and especially if it does at a very fast pace, care has to be taken to regulate this. The South African experience lends support to the view that private sector credit expansion at very high levels might lead to output volatility and adverse growth effects. In order to prevent future crises and foster economic development, a re-orientation towards more business credit, particularly for productive investment, might be needed.

Limited dat...