1

The ideational turn and the persistence of perennial dualisms

Andreas Gofas and Colin Hay

After a period of neglect, if not hostility, towards ideational explanations, where scholarship on ideas was conducted by a few dedicated researchers on the fringes of the discipline, we are now faced with a burgeoning literature on the role of ideas. Contemporary political analysis – broadly conceived – is awash with talk of ‘ideas’, to the extent that, as Jacobsen (1995: 283) notes, it now seems obligatory for every work to consider the ‘power of ideas’ hypothesis – even if only then to dismiss it. Indeed, even Moravcsik (2001: 185), one of the most materialist students of European integration and political analysis, now concedes that ‘[s]urely few domains are more promising than the study of ideas’. It is this (re)turn to ideational explanations in political analysis that forms the central focus of this book. This turn has taken a variety of different forms and can be understood from different vantage points. But as this already hints, despite the proliferation of ideational accounts in the last decade or so, the debate remains caught up in a series of heated disputes over the ontological foundations, epistemological status and practical pay-off of the turn to ideational explanations. It is thus unsurprising that there is still little clarity about just what sort of an approach an ideational approach is and about what it would take to establish the kind of fully fledged ideational research programme many seem to assume has already been developed.

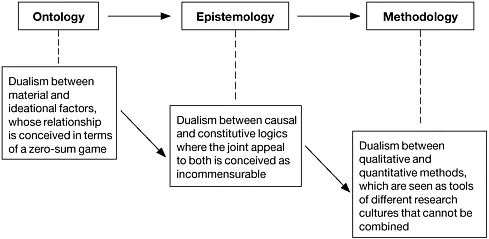

Given the diversity of the intellectual topography of ideational explanations, the purpose of this volume is not to produce some new orthodoxy. Rather, the contributors engage with the above general dilemmas in diverse but engagingly complementary ways. Nonetheless, what unites them is the assertion that what maintains the heated disputes over the status of ideas and what, at the same time, plagues most attempts to accord ideas an explanatory role is the persistence of the perennial dualisms in political analysis. Figure 1.1 offers a pictorial representation of these dualisms at the ontological, epistemological and methodological level of analysis.

At the level of ontology, the persistence of a dualistic thinking is manifest in terms of the reference to ideational and material factors as independent entities that are locked in a struggle with each other for dominance. It is this commitment to a dualistic ontology that leads Peter Hall to argue that

‘contemporary political science is gripped by a neomaterialism even more reductionist than that of the Marxist analyses of the 1960s and 1970s’ (2005: 129). Although we would not necessarily go as far as to talk of a dominant reductionist neomaterialism, one of the core features of the ideational turn within rational choice theory is an irreducibly materialist conception of (self-) interest, where ideas are grafted on to existing rationalist accounts as an auxiliary variable only if, as and where necessary (Blyth 1997). The contaminating effect of dualistic thinking also appears in accounts of self-styled constructivists, albeit in a concealed and less intense form, when uncertainty is conceptualised as an exogenously induced critical juncture that provides the structural preconditions for the causal efficacy of ideas and constitutes the only period under which they matter.

At the level of epistemology, dualism takes the form of a binary opposition between the allegedly incommensurable causal and constitutive logics – a mirror image of the explaining versus understanding controversy (see, for instance, Hollis and Smith 1990). Within a causal logic, ideas are treated as distinct ‘variables’ whose power can be established only by demonstrating a mechanistic and autonomous effect of ideational factors on specific (political) outcomes. Within a constitutive logic, by contrast, ideas provide the discursive conditions of possibility of a social or political event, behaviour or effect. This distinction leads many scholars to locate ideational explanations in the realm of understanding that is distinct from causal explanation. In effect, the current vogue for epistemological polemic between causal and constitutive logics continues to plague almost all of the literature that strives to accord an explanatory role to ideas.

At the level of methodology, dualistic thinking takes the form of a sharp divide between qualitative and quantitative methods. The debate between proponents of each of the associated research traditions is as heated as those at the ontological and epistemological level to the extent that comparisons between them sometimes call to mind religious metaphors (Mahoney and Goertz 2006; Moses and Knutsen 2007). This is hardly surprising once we realise that this distinction is fuelled by sharp philosophical assumptions according to which qualitative methods are associated with an idealist ontology and a constitutive/interpretative epistemology, while quantitative methods are associated with a materialist ontology and a causal/explanatory epistemology. While fully acknowledging the importance of the directional dependence between ontology, epistemology and methodology (Hay 2002), and despite our own insistence on their consistency, we have to recognise the inconclusiveness of the philosophical assumptions informing contending methodological persuasions. In this context, it might be ‘worthwhile to set aside the quest for uniform methodological tenets in favour of greater methodological pluralism, shifting the focus from common rules or standards to a common appreciation of the trade-offs involved in pursuing different methods and research products’ (Sil 2000: 500).

Landman (2008: 179) argues that the importance of the above dichotomous representation between materialist and idealist ontologies, causal and constitutive epistemologies, and quantitative and qualitative methodologies has been overstated by being invoked for rhetorical purposes and in the context of constructing false dichotomies. Indeed, the oppositions upon which these dualisms rest have been criticised for misrepresenting the relationship between different modes of inquiry, and, in so doing, for overplaying distinctions that are much thinner than formally stated by such schemes (ibid.). If that is the case – that is, if these dualisms and the associated sense of disciplinary unease they generate are mostly self-fabricated – then we might just as well simply be sustaining fashionable disciplinary polemics that cannot be overcome. This is an important point. Yet we contend that, schematic and overstated as these dualisms may sometimes be, they do not simply represent shorthand expressions for analytical convenience. Rather, they capture real tendencies in political analysis, where these dualisms have colonised our collective disciplinary registry and provided the backdrop of the discipline’s self-image.

The above point brings us to another related potential criticism. As Topper (2005: 13) perceptively and ruefully notes, this schematic representation of the field as paired dichotomies

The contributors to this volume, in aspiring to eschew the current vogue for dualistic polemic, do not replace one opposition with a new one. Rather, the purpose is to reveal elements of dualistic thinking in the ideational turn and to assess the impact of the persistence of this perennial dualism in the attempt to accord ideas an explanatory role.

The structure of the book

The volume contains ten chapters divided among three sections. This short introduction is followed by chapters by Gofas and Hay, Lars Tønder, and Leonard Seabrooke that provide theoretical reflections on the ideational turn. Gofas and Hay engage in a ground-clearing exercise. The fact that the ideational turn spans several theories, with differing, if not competing, ontological and epistemological underpinnings, has served the development of an often unacknowledged perception of ideas as ontologically neutral variables that can be arbitrarily invoked when and if a materialist explanation is inefficient. Yet, as they argue, ideas are far from innocent variables – and can rarely, if ever, be incorporated seamlessly within existing explanatory and/or constitutive theories without ontological and epistemological consequence. Because of this inadequate reflection on the consequences of ‘taking ideas seriously’, too much ostensibly ideational scholarship in political science and international studies is ontologically and/or epistemologically inconsistent. The authors contend that this tendency, along with the limitations of the prevailing Humean conception of causality and the associated epistemological polemic between causal and constitutive logics, continues to plague almost all of the literature that strives to accord an explanatory role to ideas. In trying to move beyond the current vogue for epistemological polemic, they argue that the incommensurability thesis between causal and constitutive logics is credible only in the context of a narrow, Humean, conception of causation. If we reject this in favour of a more inclusive (and ontologically realist) understanding, then it is perfectly possible to chart the causal significance of constitutive processes and reconstrue the explanatory role of ideas as causally constitutive.

Tønder addresses the central epistemological dualism of the ideational turn heads on with a chapter devoted to ideational analysis and the question of causality. His central claim is that ideational analysis has been brought to an impasse because scholarship has been forced to choose between (a) defining the framework of ideational explanation in such a way that it adheres to the dominant concept of efficient causality or (b) refuting the concept of causality altogether as inadequate. This dichotomous straight-jacket he finds unsatisfactory and proposes that the alternative is to be found in the concept of immanent causality that draws its inspiration from thinkers such as Spinoza and Deleuze. This conceptual reformulation of causality follows from the proposition that the ideational and the material are equivalent in an ontological sense. Moreover, a basic claim of immanent causality is that the cause and the effect are so closely related to each other that it is impossible to assume a strict separation between them. That is because ideas, by virtue of causing the world to follow a specific rather than any other path, become the very stuff that gives meaning to the outcome of this path. In so doing, the ideational ends up on both sides of the cause and effect divide. In that sense, immanent causality also provides the conceptual resources to break away from linear notions of time and change and to appreciate the ways in which feedback loops of various sorts place the causality of ideas into circulation.

The final chapter of the section, by Seabrooke, explores three main approaches to institutional change in comparative and international political economy – rationalist and historical institutionalism and economic constructivism. His central line of criticism is that the ideational turn in institutional theory has been focused primarily on elites whose ideational entrepreneurship is to provide the reconstitution of the perceived self-interests of the population at large. In effect, the masses are left as ‘institutional dopes blindly following the institutionalized scripts and cues around them’ (Campbell 1998: 383), and their role in providing impulses for institutional change is obscured. A second point that the chapter raises is that the perennial ontological dualism of material and ideational factors bedevils even economic constructivism by means of reappearing in the concealed, yet no less important, form of a selection bias towards moments of uncertainty. This bias prevents the development of a strong sense of legitimacy. Contra this, Seabrooke puts forward the view that periods of ‘normality’ are just as significant as, if not more important than, periods of crisis and uncertainty. Put differently, the focus on everyday politics provides a challenge to this aspect of the ideational turn, and invites us to re-examine the social sources of political and economic change.

The next section of the volume is on ideas, discourses and policy out comes. As the opening chapter by David Hudson and Mary Martin points out, there have been rather too many sweeping claims made in the name of ideas and rather too few examinations of the concrete mechanisms by which ideas become institutionalised. This is, in essence, the central focus of this section, which, nonetheless, does not lose sight of the perennial dualisms of the ideational turn. So, Hudson and Martin focus on the importance of media narratives in the reproduction of public discourse. By examining the case of the collapse of the London-based Barings Bank, they unravel the mechanisms by which neoliberalism as the dominant discourse is reproduced through media accounts. Against the material–ideational dualism, they claim that the reproduction of ideas and hegemonic narratives cannot be reduced solely to the interplay of material interests, but should be seen as a much more mundane affair accomplished via everyday practices. In the Barings case it was everyday media practices that explain why the concept of the rogue trader became ingrained within the public and policy-making discourses. By revealing the symbiotic relationship between a dominant idea and its modes of representation, they first add an important media-based perspective to our understanding of ideational factors, and, second, reveal additional mechanisms at work in the way ideas are disseminated. Furthermore, a major goal of the chapter is to question the tendency of ideas to remain vague and amorphous. Indeed, the examination of micro-ideas, such as that of rogue trading, challenges the unfortunate portrayal of discursive regimes as monolithic and secure ideologies that are singular in their effects. Contra this, they maintain that it is essential to move from macro- to micro-ideas, because each moment is contested on its own terms and may draw upon an inconsistent variety of different discourses which are not necessarily logical.

The following chapter by Oliver Kessler explores a central concept in the discourse of the ideational turn, namely uncertainty. He argues that ideas do not produce only the things we know but also those that we do not know. For example, the rise of derivates in financial markets has created not only new knowledge about how to manage risks but also new non-knowledge in the form of new systemic risks, unfamiliar contingencies and unintended consequences. Because of that his contribution approaches the notion of uncertainty by focusing on the structure-forming capacity of non-knowledge. That is, it examines the role that the production of non-knowledge, which is as socially constructed as that of knowledge, plays in examining the ideational foundations of social institutions. In the course of his analysis, he challenges both the utility of the dominant notion of efficient causality, together with its associated epistemological underpinnings, and the mainstream treatment of uncertainty as structural informational asymmetries. Rather, he argues, echoing the argu...