1 Social paradigms in China and the West

William E. Shafer

Introduction

Recent research has found that the extent to which individuals subscribe to the dominant social paradigm (DSP) of Western societies is a critical determinant of their attitudes toward social and environmental issues (Shafer 2006; Kilbourne, Beckman and Thelen 2002; Kilbourne, Beckmann, Lewis and Van Dam 2001). The DSP concept, initially developed by social psychologists (Milbrath 1984; Dunlap and Van Liere 1984; Pirages 1977), is generally recognized to include economic, political and technological dimensions. The economic dimension includes attitudes such as support for free market capitalism and belief in the possibility and desirability of unlimited economic growth. The political dimension is usually theorized to include support for limited or no government regulation, private property rights and individual freedom. The technological dimension includes such tenets as belief in the ability of science and technology to solve mankind’s challenges and a concomitant faith in future material abundance and prosperity.

The world view encapsulated in the DSP appears tailor-made to support the neoliberal agenda of unfettered capitalism, and indeed many would suggest this system of beliefs has been socially constructed and propagated by economic elites for this very reason (cf. Shafer 2006). Although the DSP concept was developed to describe the dominant world view supporting late twentieth century Western capitalism, the current environment of globalization has obviously encouraged the adoption of similar beliefs worldwide. Indeed, the long-standing backlash against globalization is a testament to resistance against the forced imposition of the world views of Western capitalism. Given that the DSP supports a system that is arguably allowing corporations to inflict serious harm to the biosphere (Bakan 2004; Kelly 2001; Korten 1999, 1995), it is important to understand the extent to which this perspective is being adopted worldwide.

There are particular reasons to be concerned about the influence of the DSP in the People’s Republic of China. It has been well documented for years that China’s economic development and expansion have come at a tremendous cost to the environment and, consequently, public health (Economy 2004; Edmunds 1998). Although the Chinese government has recently attempted to rein in environmental degradation, the problems have continued to mount, and accounts of China’s environmental crises regularly appear in the media (Leslie 2008; Ziegler 2007; Economy 2007; Engardio, Roberts, Balfour and Einhorn 2007; Kahn and Yardley 2007; Yardley 2007a, 2007b, 2007c). As observed by Harris (2006: 5),

‘One would be hard pressed to find a more explicit and profound example of how human behavior can adversely affect the ecological environment than the ongoing experience of China. A huge population and rapid economic growth have conspired to create an expanding environmental catastrophe.’

Harris (2006: 6) goes on to suggest the root causes of most of China’s environmental problems are ‘the behaviors and underlying attitudes of the Chinese people. How they perceive and value the environment will largely determine how they behave in relation to it.’

A central premise of this chapter is that one should look deeper than the manifest attitudes and behaviors of the citizenry and question the systemic factors that produce and replicate such attitudes and behavior. For instance, the concept of the DSP highlights the role of economic and political elites in promoting ideologies that may profoundly influence individuals’ world views. Thus, obtaining a greater understanding of the role and influence of social paradigms in contemporary China seems to be part of a much-needed examination of the underlying conditions contributing to the country’s social and environmental problems.

Social paradigms and corporate social responsibility

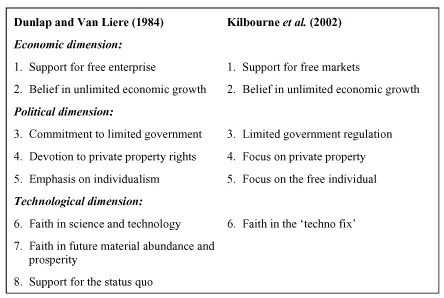

Before discussing the relationship between social paradigms and corporate social responsibility, it is helpful to examine more closely the concept of the dominant social paradigm, and the alternative perspective commonly referred to as the new ecological paradigm. The basic concept of the DSP is similar to Kuhn’s (1962) notion of scientific paradigms, which define accepted ways of thinking about particular issues and tend to be quite resistant to change. Although there have been many conceptualizations of the DSP in varying degrees of detail, Figure 1.1 illustrates the similarities between the DSP elements theorized in two influential papers, those of Dunlap and Van Liere (1984) and Kilbourne et al. (2002). As shown in the Figure, both conceptualizations include support for ‘free enterprise’ or ‘free markets’ and belief in the feasibility of essentially unlimited economic growth, ideas collectively described by Kilbourne et al. (2002) as the economic dimension of the DSP. They also share three key political elements: a commitment to limited government regulation, an emphasis on private property rights and a focus on individualism or individual ‘freedoms’. Dunlap and Van Liere propose two closely related ideas combined by Kilbourne et al. as ‘belief in the techno fix’: faith in the ability of science and technology to solve environmental problems, and a resulting confidence in future material abundance and prosperity. Dunlap and Van Liere also include support for the status quo as an element of the DSP; however, as argued by Shafer (2006), support for the status quo can be thought of as a characteristic of paradigms in general rather than a component of any particular world view.

Figure 1.1 Dominant social paradigm (DSP) components.

The concept of a dominant social paradigm is consistent with Gramsci’s (1971) theory of hegemony, which recognizes that social and political elites attempt to maintain their power by promoting certain preferred ideologies or ways of thinking (Bates 1975). The concept is also broadly consistent with many classic works of political theory that question the possibility of true democracy in modern nation-states, assuming that societies are controlled by ‘power elites’ that use various mechanisms (such as media control) to mould and subvert the will of the masses (Dahl 1961; Mills 1956; Schumpeter 1947; Mosca 1939). If public opinion cannot be controlled through such ‘soft’ mechanisms, the ruling elites may be forced to resort to state-sanctioned (i.e. military) violence to maintain their position of power and control.

It has been argued for years that the DSP is being supplanted by a more enlightened world view referred to as the new environmental paradigm or new ecological paradigm (NEP) (Cotgrove 1982; Dunlap and Van Liere 1978; Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig and Jones 2000). The NEP generally reflects a variety of common environmentalist perspectives, such as limits to growth in a finite ecological system, the belief that we are facing a man-made ecological crisis and a lack of faith in the ability of science and technology to rectify ecological challenges. Given the obvious contrast between this perspective and key elements of the traditional DSP, it is not surprising that several studies have found strong negative correlations between these alternative perspectives (Shafer 2006; Kilbourne et al. 2001; Kilbourne et al. 2002).

Reflection on these competing world views clearly suggests that belief in the DSP should be negatively associated with support for corporate social responsibility, while support for the NEP should be positively associated. The DSP emphasis on ‘free’ or self-regulating markets and limited government regulation are consistent with the classic neoliberal arguments that any form of regulation or constraint of market behavior is unnecessary and counterproductive, and that the only ‘social responsibility’ of business in a capitalist system is to maximize profits within legal constraints (Friedman 1962). Belief in the feasibility of unlimited economic growth and in the ability of science and technology to solve environmental problems should reinforce opposition to social restraints on corporate behavior by reducing the perceived moral intensity of threats to the natural environment.1 In contrast, the world view encapsulated in the NEP should greatly increase the perceived moral intensity of environmentally harmful corporate behavior, leading to demands for the enforcement of standards of corporate social responsibility. This line of reasoning suggests the DSP may be a significant impediment to substantive advances in corporate social responsibility.

Political, economic and social context in China

It seems apparent that since embarking on the transition from a state-controlled to a market-based economy, China’s leaders have been searching for an identity and an ideology that will justify and rationalize the country’s economic, political and social order. The aggressive pursuit of market reforms directly clashes with the socialist ideology of Marx and Mao that provided the unifying framework for the country after 1949. How to rationalize the transition to capitalism yet justify the retention of an authoritarian political regime designed for a state-controlled economy became a central problem for Chinese leaders (Bell 2007; Knight 2003; Wang 2003; Burton 1987). The need to maintain the legitimacy of the ruling communist party led the central government to insist that the country was transitioning to a ‘socialist market system’ or a system of ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ (Chai 2003; Burton 1987). Socialism remains the official ideology of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and the stance of the CCP is that ‘the current system is the “primary stage of socialism”, meaning that it’s a transitional phase to a higher and superior form of socialism …’ (Bell 2007: 1).2

It is well known that many intellectuals have been highly critical of such arguments over the past two decades, as the fundamental conflict between the official ideology of socialism and actual economic practices widened (Wang 2003; Chen 1995; Kwong 1994; Burton 1987). The CCP leadership has long been criticized for failing to even provide basic definitions for catchphrases such as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’. Reviewing early criticisms of the disconnect between socialist ideology and market reforms, Burton (1987: 437) suggested the most striking characteristic of the party’s attempt to redefine its role in society was a ‘complete lack of reliance on any theoretical rationalization for the change’. Influential Chinese scholar Wang Hui (2003) argues that the economic and social policies pursued by the Chinese government since the mid-1980s reflect an underlying neoliberal ideology, with its emphasis on unregulated free markets and assimilation into the system of global capitalism.3 Beginning with Deng Xiaoping’s famous invocation in the late 1970s, ‘To get rich is glorious’, there has been a general obsession in China with wealth creation and economic growth (Yan 2006; Harris 2005; Smil 1996). Wang (2003) argues that in contemporary China the single-minded pursuit of growth and development has trumped all other concerns, including social justice and democracy.

The Chinese government has, implicitly or explicitly, endorsed many of the characteristics of neoliberalism while at the same time refusing to abandon its official mantra of socialism. China’s neoliberalism

… sought to radicalize the devolution of economic and political power in a stable manner, to employ authority to guarantee the process of marketization in turbulent times, and to seek the complete withdrawal of the state in the midst of the tide of globalization.

(Wang 2003: 81)

The pursuit of this radical free-market agenda led to numerous social problems as the wealth and income gaps between the new capitalists and the majority of China’s population widened, creating tension between the official ideology and economic realities. Deng Xiaoping modified China’s

pristine socialist ideology into a variant form of reform socialism … the Chinese leader denounced egalitarianism for retarding progress and tolerated and advocated measures that increased income polarization … They ignored the contradictions. Instead they emphasized the pragmatic benefits and called themselves socialists.

(Kwong 1994: 249)

By the time of the initial publication of his essay on China’s ‘neoliberalism’ in 1997, Wang’s frustration with the situation was evident:

… the Chinese government’s persevering support for socialism does not pose an obstacle to the following conclusion: in all of its behaviors, including economic, political, and cultural – even in governmental behavior – China has completely conformed with the dictates of capital and the activities of the market.

(Wang 2003: 141)

Thus, many intellectuals have long dismissed any residual pretensions of the Chinese government to ‘socialism’. But what has perhaps been most troubling about China’s ‘transition’ to a market economy has been the perception of systemic corruption in the devolution of economic and political power, in particular, the common belief that public assets were being transferred to party elites (Wang 2003; Dickson 2001, 1999; Kwong 1994). This perception, combined with the government’s insistence on adhering to socialist ideology at a time of growing wealth and income inequality, created the crisis of state legitimacy that led to the 1989 social movement (Wang 2003). The basic demands of this movement included

‘… opposition to official corruption and peculation, opposition to the “princely party” …, demands for social security and fairness, as well as a general request for democratic means to supervise the fairness of the reform process and the reorganization of social benefits’

(Wang 2003: 57)

However, there was a fundamental conflict between these popular demands and the interests of ruling elites in a system of radical privatization, and ‘collusive links’ between these elites and the ‘world forces of neoliberalism’ (Wang 2003: 62). What took place under the guise of ‘free markets’ and ‘privatization’ in China ‘… was the creation of interest groups that colluded to use their power to divide up state resources, used monopoly power to earn super profits, and worked in concert with transnational or indigenous capital to seize market resources’ (Wang 2003: 101).

Wang (2003) sees no inherent conflict between the authoritarian Chinese state and neoliberalism, arguing that neoliberalism often relies on state power for its enforcement. He is highly critical of the common assumption that the process of market reforms in China will inevitably lead to political democracy, arguing that the proponents of this assumption have failed to analyze in any meaningful detail the mechanisms through which this transformation would occur.4 Indeed, Wang (2003: 122) emphasizes that modern capitalism (as opposed to truly ‘free markets’) is a system that relies on and tends towards monopoly power, and since the failure of the 1989 social movement in China it has depended critically on the power of the central government ...