![]()

1

Introduction

Food and finance

In 2008, skyrocketing food prices were the source of riots and destabilization in almost thirty countries around the globe. From Haiti to Egypt to Panama and the Philippines, rising food prices created turmoil for countries reliant on imported foodstuffs. Was this the specter of Parson Malthus? Had global population finally outpaced our ability to produce food? Or was it simply the workings of a commodity super-cycle brought on by growing global demand from the BRICK countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and Korea) combined with supply disruptions from poor harvests?

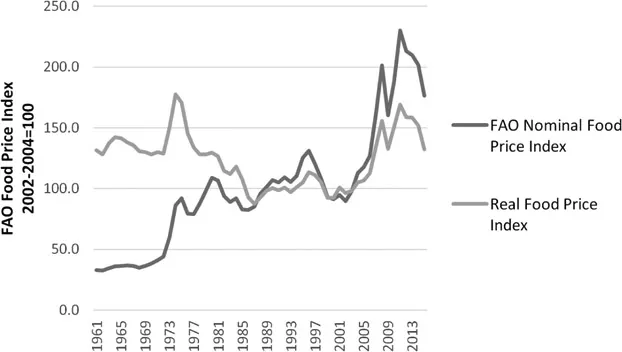

Figure 1.1 FAO Food Price Index.

From 2002 to 2008 the nominal value of the FAO Food Price Index increased by 125 percent, and the most dramatic increases occurred in 2007 and 2008, with prices rising by 26 percent per year in nominal terms and 18 percent in real terms (Figure 1.1). Attempts to explain the cause of higher food prices have primarily laid blame on a super-cycle driven by global demand from China, with secondary causes attributed to biofuel mandates, supply disruptions, a decline in the US dollar, and financial speculation. Speculation has been the most controversial of the explanations offered, and a “speculation debate” was triggered when, in a May 2008 testimony to the US Senate, investment manager Michael Masters blamed high commodity prices on a price bubble in the futures markets driven by a new class of speculators, commodity index traders (Masters, 2008). Masters presented data (Figure 1.2) which showed that the growth of funds flowing into passive commodity index investments mirrored the rise in commodity spot prices. Investment flows into these new commodity-based financial products from pension funds, endowments, and other investors were driving up commodity prices, and therefore food prices.

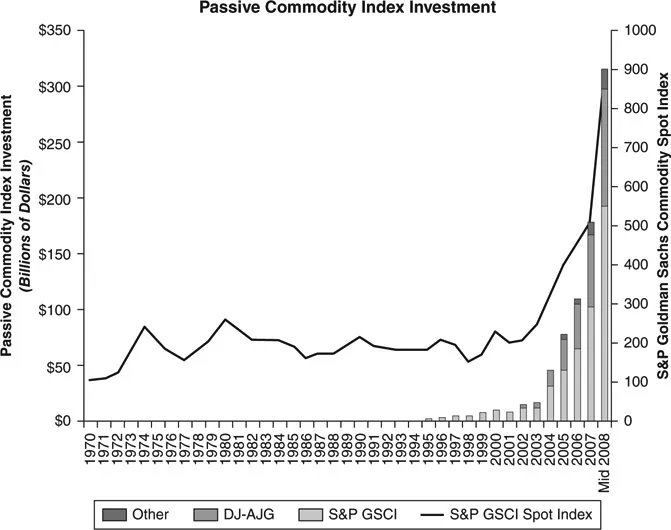

Figure 1.2 Commodity index investments and commodity prices.

Masters’ testimony set off a vigorous debate over what appeared to be an obvious relationship. Was it a statistical mirage? Hundreds of academic papers have since been written in an attempt to settle this “simple” question: did financial speculation in the futures market cause an increase in commodity prices? Based on the arguments made in this work, the simple answer is yes. The complex answer is that financialization of futures markets transformed commodities into an asset class, allowing financial traders to determine the course of prices in the short run: financialization of commodity markets explains how, but not the extent to which, financial speculators contributed to the 2008 food price bubble.

The main argument in this work is that financial interests, large Wall Street banks, used a financial innovation to circumvent regulations and break down barriers to entry in the regulated commodity futures markets; then, through political influence, the innovations were codified through a deregulatory act. This financialization process resulted in a “flipping of the markets,” where financial traders, previously restrained, now dominate markets and determine the direction of prices in the short term. Financialization has transformed commodities into an asset, and like all asset prices, commodity prices have become more volatile and they are subject to periodic bubbles.

Financialization of physical things creates new markets and profit opportunities for financial traders, and volatility is good for profits because it increases the demand for financial products used to hedge against price movements. In a low-yield environment, or what former PIMCO managing director Bill Gross (Gross, 2009) called the New Normal, investors are motivated to find new, alternative investment outlets. With trillions of dollars chasing yield, commodities, farmland, water, climate, utilities, and even sewage disposal are fair game.

The term financialization has been used to describe this encroachment by finance into new markets and its influence over the broader economy. While there are several definitions, the one most often cited is Epstein (Epstein, 2005), “Financialization refers to the increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operation of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international level” (p. 3). Financialization is one of several institutional forces that have shaped the US economy over the past forty years, and food prices, industries, and food systems have not been immune from its influence.

This influence of finance along with the re-emergence of market fundamentalism and trade liberalization are characteristics of what has been described as the neoliberal capital accumulation regime by Regulation and Social Structure of Accumulation (SSA) schools of thought (Kotz, 2010). In these approaches, the accumulation process under capitalism is characterized by regimes, or institutional arrangements, that emerge to facilitate long periods of capital accumulation. Neoliberalism, then, is the set of forces that arose out of an accumulation crisis in the late 1970s, and these forces have established new institutional arrangements which govern the current accumulation process. However, as we discuss, financialization has become the dominant force regulating the accumulation process since 2000.

As argued in this work, financialization of commodity markets allows financial traders to determine prices in the short run, and it is one of several factors underlying the 2008 food price bubble. However, as one of the forces under the neoliberal accumulation regime, financialization helps explain broader long-term changes in the US and global economies. As a process, financialization has directly impacted commodity markets and food prices; however, as a broader force, it has influenced food markets and systems in other, less obvious, ways. Neoliberalism and financialization have literally changed the shape of American society and its people.

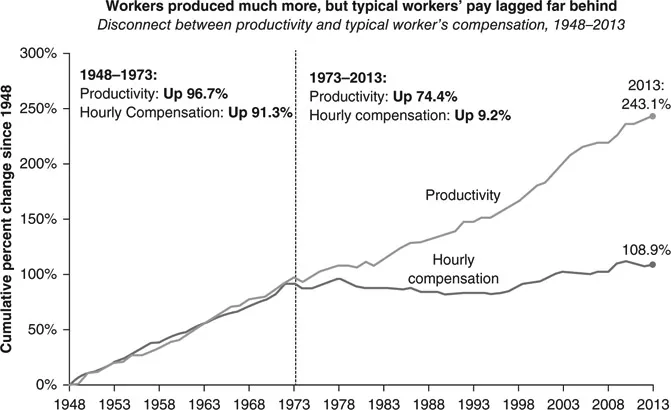

Figure 1.3 Productivity and worker compensation.

The main goal of neoliberal policies was restoring profitability through deregulating markets, expanding trade, eliminating barriers to capital mobility, and eroding the social safety net. In addition, at the level of the firm, a revolution in shareholder activism led to management compensation policies that produced a focus on short-term value creation. The result of these policies was the breakdown in the post-war social compact tying wage gains to productivity, as shown in Figure 1.3. The loss of high-wage union jobs to low-wage competitors and the erosion of the social safety net reduced labor’s bargaining power, which allowed the gains from productivity to flow to shareholders and managers in the form of higher profits and stock prices.

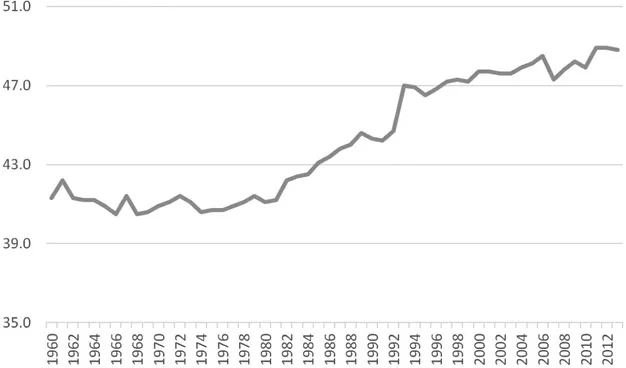

Neoliberal supply-side economic policies were used to justify tax cuts for capital and high-income earners, which saw the top marginal tax rate in the US lowered from 70 percent in 1980 to a post-war low of 28 percent in 1988. As more income flowed to the top, measured inequality worsened (Figure 1.4). From 1980 to 2013, the share of family income received by the top quintile increased from 41.1 to 48.8 percent, with over 90 percent of the gains going to the top 5 percent, increasing their share from 14.6 to 21.1 percent.

As the structure of the US economy was changing, so too was the social structure. As wages stagnated, two-income families became the norm. From 1967 to 1990, the number of families with two-income earners increased from 43.6 percent in 1967 to 59 percent in 1990. As financial duress increased, the divorce rate increased in the 1970s and 1980s, and the number of households headed by a single parent doubled from 11.9 percent in 1970 to 24.3 percent in 1988 (Current Population Survey).

Figure 1.4 Share of family income, top 20 percent.

These economic and social changes, in turn, helped transform the US food system and Americans themselves. With less time and money, the American diet has shifted toward cheap and convenient in the form of fast, processed food, leading to what Eric Schlosser called the Fast Food Nation (Schlosser, 2012). Small fast-food joints became big global fast-food chains which required food sources of equal size. Large industrial farms were needed to feed the sugar to Pepsi and Coke and the tomatoes for the 25,000 global pizza locations of Dominos and Pizza Hut (Kaufman, 2012). These changes are not without consequences.

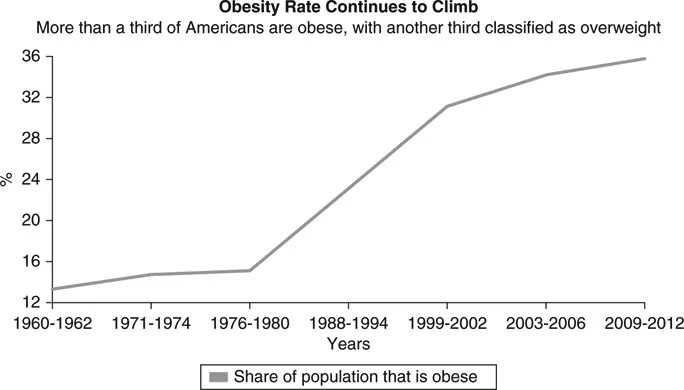

The trends in wages, inequality, and family structure that began in the 1970s have a counterpart in our health. Americans have become increasingly obese, and it is by no means a coincidence that the trend in obesity (Figure 1.5) mirrors the trends in stagnant wages and inequality – economic variables influence obesity (Courtemanche et al., 2015). Obesity is associated with serious health conditions including high blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and cancer among others (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Obesity also creates significant economic costs in the form of lower productivity and higher medical costs, and it was estimated that widespread obesity increased medical spending in the US by $316 billion in 2010 (Stilwell, 2015).

The US spends more money on healthcare than any other advanced nation, yet it ranks near the bottom among advanced nations in health rankings. A recent report by the National Research Council and Institute of Medicine ranked the US last out of 17 advanced countries, and Americans were in poorer health across the lifespan, from infancy to old age (Rubenstein, 2013). We have more and better healthcare, but the number of Americans reporting they are healthy has dropped from 39 percent in 1982 to 28 percent in 2006 (Grabmeier, 2015). In many cases, food is literally killing us:

Food sickens 48 million Americans a year, with 128,000 hospitalized and 3,000 killed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates. The rate of infections linked to foodborne salmonella, which causes the most illnesses and deaths, rose 10 percent from 2006 to 2010.

(Armour et al., 2012)

As more people awaken to the connections between food and health, reactions to the globalized, industrialized, financialized food production system are growing.

Figure 1.5 US obesity rate (share of population).

In this book we attempt to illuminate some of the main connections between finance and food. In many cases the connections are clear, as in the financialization of commodity markets; in other cases, they are less so, since finance is a broad force which influence many aspects of economic activity. In the next section we outline the path taken in this work.

Outline of the book

The purpose of this work is to describe the ways in which financialization has influenced the US food system; however, as the largest market in the world, the US food system, in turn, influences the global food system. We focus on three primary finance–food connections. First, we described the financialization of commodity futures markets which has transformed food into an asset. Since asset prices are subject to the whims of investors, they are more volatile than goods’ prices and are prone to bubbles. The second area of interest, connected to the first, the long-term rise in agriculture commodity prices from the early 2000s to 2012 has increased the value of farmland, and investors in search of yield in the New Normal environment are buying up farmland around the globe. Third, one of the most important agents of change in the financialization regime is the private equity (PE) firm, and the PE industry has fueled a merger and acquisition (M&A) boom through leveraged buyouts (LBO) that has raised corporate debt levels and increased concentration. While private equity deals influence all industries, the food industry has the characteristic that lends itself to takeovers, stable growth that generates steady cash flows.

The food system is a complex organism, and describing the forces that have shaped it over time is no easy task. As a way to incorporate the development of food systems over time into the broader economic framework of accumulation theories, we adopt food regime theory (McMichael, 2009). Food regimes are the analogue of regulation and SSA theories, and we introduce this framework in Chapter 2. While food regime theorists identify two clear regimes covering the period from 1850 to 1970, there is less agreement in describing the period that begins with the emergence of neoliberalism (Burch and Lawrence, 2009). For purposes of this work, and as outlined in Chapter 2, we identify the late 1970s to 2000 as the neoliberal regime, and the post-2000 period as the financialization regime.

One of the main goals of Chapter 2 is to formalize the concept of financializaton. While Epstein’s definition may be cited most often, there are competing definitions, so we survey the literature to identify alternative concepts, then set out definitions of financialization used in this work. In modern h...