![]()

1 States and Social Fields

If no social institutions existed which knew the use of violence, then the concept of ‘state’ would be eliminated, and a condition would emerge that could be designated as ‘anarchy’, in the specific sense of this word.

– Max Weber, Politics as a Vocation

Human beings cannot live and exist except through social organization and cooperation for the purpose of obtaining their food and other necessities of life. When they have organized, necessity requires that they deal with each other and satisfy their needs. Each one will stretch out his hand for whatever he needs and (try to simply to) take it…. The others, in turn, will try to prevent him from taking it, motivated by wrathfulness and spite and the strong human reaction when one’s own property is menaced. This causes dissension.

– Ibn Khaldoun, The Mokadima

In this book I argue that what emerged in the Middle East with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire should better be conceptualised as social fields rather than states. Social fields, which initially constituted the spheres of influence of the encroaching European powers, are the social arenas where states form or de-form and develop. Examining states in the Middle East as social fields will form a useful point of entry to study the state in that region, and to understand its nature, dilemmas, and interaction with the international system. In this chapter I will first present a conceptual analysis of the state and will then introduce my social field model.

The concept of the state, like many of its counterparts in the social sciences, has been both indispensable and confusing for sociopolitical analysis. As a social configuration, the state is an expression of varying levels of human interdependence; as a social actor, the state plays an influential role in domestic social order and disorder, and in international wars and peace; as a social organisation, the state forms the arena in (and through) which social groups negotiate their conflicts. Given the varying roles, functions, and identities that shape state character in different contexts, it should not come as a surprise that state theories have offered divergent accounts and definitions of the state. Professional and disciplinary divisions in the social sciences have also limited the dialogue among students of the state, which has left a negative impact on our understanding of that social organisation. For example, when students of comparative politics (CP) sought to ‘bring the state back in’ (Evans et al. 1985), their counterparts in international relations (IR) were trying to turn away from the state and realism’s obsession with it (Keohane 1986). While war as an interstate conflict had always been a central concept in IR, it was only brought into CP in the 1970s and 1980s to fill gaps left by the modernist theory (Tilly 1975a). In CP the state is conceived as a solution for anarchy at the domestic level, while in IR the state is assumed to cause anarchy at the international level. The study of state formation, however, falls not only at the crossroads of these subfields of enquiry, but also at the nexus of international and domestic political arenas. Understanding state formation initially involves loosening the boundaries that demarcate these fields. But first we must ask: what is a state?

I The State as a Process

As a point of departure, it is important to provide a definition of the state as an organisation – a model entity. This should precede the definition of state formation, as that would raise the question: the formation of what? Accordingly, I will start with Max Weber’s definition of the state. Weber’s definition represents an ideal model state, which, and specifically for the purposes of this study, helps us not only to contrast it with historical realities but also to theoretically problematise it in order to understand late-forming states. Defining the state is not a theoretically innocent enterprise. As a social organisation, state definition cannot escape the student’s theoretical assumptions, his or her research aims, or, in some cases, their ideological biases. The state, accordingly, is seen to be the ‘most problematic concept in politics’ (Vincent 1987: 3).

For Weber, states are ‘compulsory political organizations’ whose ‘administrative staff successfully upholds the claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical forces in the enforcement of its order … within a given territory’ (1978: 54, emphasis original). As an authoritative political organisation, the state is made up of different governmental institutions such as security and intelligence agencies, the court system or executive and legislative branches of government. It is authoritative in the sense that its policies and rules are recognised by those that it seeks to govern. Deviation from these rules involves the state exercising compulsion – or coercion – over the lawbreakers. This ability, however, requires the presence of a monopoly of physical force, which Weber’s definition highlights. For the state to be able to exercise its power to impose order, it alone should hold the instruments of coercion. But Weber is clear in tying this monopoly over coercive forces to legitimate use and, by implication, rule.

The final element in Weber’s definition is that state activities take place within a specific territory. Its power, legitimacy, and monopolisation over coercion, at least in theory, are delimited to a particular territory. It is only the state that has a sovereign power over its territory. This legal right is recognised by other states. The delimitation of state territory places the organisation of the state at the crossroads of two sets of relationships: the first involves the relation of a state with other organisations within its territory, and the second comprises the state’s relations with other states in the international system.

The student of state formation, however, will immediately raise questions related to the Weberian definition: How does this political organisation come about? How is the monopoly of coercion formed? How does this monopoly acquire and maintain its legitimacy? And how is a state’s territory demarcated? In studying state formation, I begin with these questions. I examine the state as a process.

These questions have troubled state theorists for many centuries. Depending on the story they want to tell or the political world they want to see, scholars have treated the state as an agent of change or as an outcome of social development. Political philosophers from Thomas Hobbes to Vladimir Lenin saw the state as a vehicle for change towards order or revolution. Post-philosophical treatments of the state were largely indirect as in the case of Karl Marx, whose sophisticated class struggle analysis saw his thought fluctuate between treating the state as an epiphenomenon of class struggle, as an instrument of class hegemony, or as a political structure having a ‘relative autonomy’. It was his students like Antonio Gramsci (in 1971) and Nicholas Poulantzas (in 1978) who sought to examine these questions in detail.

In the fields of politics and sociology, the state as a conceptual variable remained largely absent until J.P. Nettl’s pioneering article of 1968. Both structural-functional approaches and modernisation theory, forming part of the behavioural revolution, perceived the state as the outcome of a social system. The project to ‘bring the state back in’ (Evans et al. 1985), which started with a re-examinion of European state formation, raised questions about modernisation theory (Tilly 1975a), and attempted to give the state an ‘autonomous’ role in social development, and hence analytical independence. The impressive economic development of East Asia contributed to state theory and debate (Woo-Cumings 1999), as students began to explore varying levels of state ‘capacity’ to drive socio-economic development (Bates 2005; Waldner 1999; Migdal 1988).

One main difficulty remaining in our understanding of the state, which still traps many students, is a supposed separation of the state from society. In the context of state formation in the developing world, Joel S. Migdal et al. aimed to define the state as one organisation among many that is situated in society (1994: 2). Trying to cope with the difficulties that the Weberian definition generates when contrasted with empirical cases, Migdal proposed a new definition of the state. The state, he observed, is a

… field of power marked by the use and threat of violence and shaped by (1) the image of a coherent, controlling organization in a territory, which is a representation of the people bounded by that territory, and (2) the actual practices of its multiple parts

(Migdal 2001: 15–16, emphasis original)

What Migdal seeks to distinguish is the ‘image’ of a state – a dominant, autonomous, integrated entity – from its actual practices. Symbolic power of the state and how it is perceived by its population and other states is crucial for maintaining its power. Migdal’s definition is a response to previous studies that have exaggerated state capacity; but his definition also approximates the reality of politics in many parts of the developing world where the ‘state is constructed and reconstructed, invented and reinvented, through its interaction as a whole and of its parts with others’ (Ibid.: 23).

It was Philip Abrams, however, (and Frederic Engels before him1) who aimed to unmask the state. When studying the state, he contended, it would cease to exist as a separate organisation. He argued that the ‘state, conceived as a substantial entity separate from society has proved a remarkably elusive object of analysis’ (1988: 61; see also Mann 1993: 23). On perception and image, Abrams observed that the ‘state is the unified symbol of an actual disunity’ (1988: 79). Instead, Abrams suggested that we study ‘the actualities of social subordination’ (Ibid.: 63). Max Weber had already distinguished between the state as a social organisation and the process of its formation. ‘Like the political institutions historically preceding it’, he argued that first and foremost ‘the state is a relation of men dominating men, a relation supported by means of legitimate (i.e. considered to be legitimate) violence’ (Weber 2001: 2).

In this book, I begin by looking at social conflict to understand the state. Examining state formation as a process of social conflict and subordination will take us beyond debates related to whether the state, as a supposed European invention, is compatible or incompatible with non-European cultures. The development, first in Europe and later throughout the world, of norms and legal notions of sovereignty and territoriality should not obscure our understanding of the underlying social and political conflicts that form the basis from which these norms have emerged. These norms did shape state formation in the Middle East and the interactions among states and between regimes and societies; however, having a legal label does not ensure sovereignty for a state in relation to other states in the system or respect and legitimacy within its borders. Sovereignty and legitimacy, like the state, are formed in processes of social development. States are not mobile products that can be exported or imported; states are social organisations that develop as a result of social subordination, integration and differentiation within particular boundaries.

In his study The Civilizing Process (2000), Norbert Elias sheds light on the process of state formation. He specifies two phases, which I believe are universal to understanding varying levels of state formation. These two phases help us both to define the process of state formation and to locate different cases in this continuum:

First, the phase of the free competition or elimination contests, with a tendency for resources to be accumulated in fewer and fewer and finally in one pair of hands, the phase of monopoly formation; secondly, the phase in which control over the centralized and monopolized resources tend to pass from the hands of an individual to those of ever greater numbers, and finally to become a function of the interdependent human web as a whole, the phase in which a relatively ‘private’ monopoly becomes a public one.

(Elias 2000: 276)

The first phase involves a situation in which many social forces are competing for power within an unspecified territory. Power is here understood as ‘the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance’ (Mann 1986: 6). The monopolisation of power – resources, coercion, religious interpretation – in a particular territory generates a need to design institutions for its sustainability. Institutional design ‘takes place in the context of powerful actors attempting to produce rules of interaction to stabilize their situation vis-à-vis other powerful and less powerful actors’ (Flingstein 2001: 108). The more interdependent the relations become between a ruler (a monopolising faction) and his population, the higher the need to institutionalise power.

In the course of the political struggles that take place, institutions become not only a target of resistance by the rivals of the ruler, but also an arena of struggle to change the rules of interaction. The higher the ability of many different actors to shape the rules and principles of these institutions, the more these institutions begin to take a public, and therefore independent, form and the less they are driven by one actor. ‘The privately owned monopoly in the hands of a single individual or family’, observed Elias, ‘comes under the control of broader social strata, and transforms itself as the central organ of a state into a public monopoly’ (Elias 2000: 270–1, emphasis added). We now call this process ‘democratisation’. It is here where the monopoly of physical forces becomes legitimate. State institutions do not only increase in size, scope and bureaucracy, but also in representation (Mann 1993: 358).

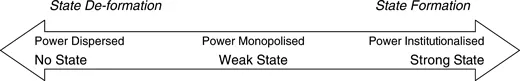

This process, as I have suggested, is generic; it presents us with a broad map of the phases of state emergence. State formation and de-formation take place within social fields, a concept I will examine in detail in the following section. The conditions of state formation, it needs to be noted here, vary among cases. Although European states crystallised around the turn of the century, many developing countries still fluctuate between one phase and the other. State formation, accordingly, is not a unilinear process. The process can reverse: states can de-form or collapse. To simplify this process, Figure 1.1 models states as a process by providing three theoretical situations that reflect different phases of state formation.

Figure 1.1 State formation/de-formation continuum.

Starting on the left side of the arrow, we have a situation where power is dispersed, where two or more power-holders – tribes, princedoms, or warlords – are each, theoretically, in a state of political autonomy. At this phase, we have power balance with no visible dominant power: a stateless situation. However, as one social power begins to dominate over others – moving rightwards in Figure 1.1 – a change begins to take place at the political level. A centre of gravity begins to emerge in a social field when one social power initiates an attempt to dominate others – the monopoly mechanism. A complimentary strategy is to articulate an ideology, usually existing within the cultural structure (I will expand on this later), to legitimise this power monopoly. This forms the seeds for the emergence of ‘public’ institutions challenging other local institutions.

Where a social power fails to subordinate other factions, a power balance would continue to exist. In such a situation a regime fails to emerge and a situation of conflict persists. In real-world cases, this can be a result of state de-formation. As opposed to state formation, state de-formation and collapse ‘refers to a situation where the structure of authority (legitimate power), law, and political order have fallen apart and must be reconstituted in some form, old or new’ (Zartman 1995: 1). It is here when the monopoly of coercive forces becomes ‘privatised’ as different factions aim to protect themselves in the absence of an authority, especially when criminality increases and the authority loses control over different sections of the population in a particular territory (Rotberg 2003: 5–6). When states de-form, power disperses to local groups, and sources of legitimacy fragment accordingly. Several states (such as Lebanon, Yemen, Somalia and Iraq) have moved in that direction during certain periods in their respective histories. What we have here are ‘competing locations of authority’ (Ayoob 1995: 4) vying to monopolise power within a delimited territory.

However, when a social force (a tribe, party, communal group, etc.) succeeds in monopolising power within a territory and institutionalises this power, a regime emerges. A regime is ‘an alliance of dominant ideological, economical, and military power actors coordinated by the rulers of the state’ (Mann 1993: 18). It is this force or forces that shape and drive state institutions in particular ways as it competes with its rivals. For example, when we say the ‘Saudi regime’, we mean the Saudi family and its ideological, economic, and military allies (the Islamic/Wahhabi establishment, its allies, and princes in armed and security forces, respectively). The presence of a dominant regime, as defined here, assumes the existence of other rivals – potential regimes – who aspire to hold power and shape the politics within a social field. In this case, when we talk about a state we are in essence referring to a regime – a constellation of social forces – that dominates other factions within a social field: not a public organisation that is ‘above society’, but an organisation driven by a regime with a specific interest in survival amidst resistance by oppositional forces. A regime is a group of men dominating other men. The capacity of this regime is determined by its relative power in relation to its competitors within a social field; the stronger the other factions are, the weaker the regime’s capacity, and vice-versa.

At this phase of state formation, we have – as Figure 1.1. shows – a power disequ...