eBook - ePub

Environment and Development in the Straits of Malacca

Goh Kim Chuan, Mark Cleary

This is a test

Share book

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environment and Development in the Straits of Malacca

Goh Kim Chuan, Mark Cleary

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This unique study is the first in depth examination of the environment and development of the Straits. Taking an integrative approach, the book argues that the region has an underlying unity which political divisions (between Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore) disguise.

Its emphasis is on three major elements: first, a study of the historical geography of the region illustrates its role as a sea-corridor which connected the markets of India and China. Secondly, that contemporary patterns of economic development and trade have continued to increase the strategic importance of the region. Finally, the text highlights the major environmental problems, such as pollution, traffic and tourism, that now threaten the sea and coastline.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Environment and Development in the Straits of Malacca an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Environment and Development in the Straits of Malacca by Goh Kim Chuan, Mark Cleary in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: A SEABORNE WORLD

The Straits of Malacca, today one of the busiest stretches of sea in the world, extend for some 500 miles from north to south between Malaysia and the Indonesian island of Sumatra, and its waters are shared between three states: Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. The Straits are narrow and crowded: at their widest they are only 126 nautical miles around the island of Penang; whilst at their narrowest, at Little Karimun, close to the adjoining Straits of Singapore, they are little more than nine nautical miles. This stretch of water, shallow, littered with sandbanks and divided up by islands large and small, together with the coastal territories, estuaries, and human settlements that abut it, has been enormously important in shaping the historical and contemporary patterns of life and livelihood in Southeast Asia. The way in which these waters, and the traffic —human, biotic and marine—upon it, have shaped this important region is the subject of this book.

That the seas, reefs, sands, islands and coasts of the Straits region have an underlying unity—that which unites them is greater than that which divides them —is the central theme which underlies the conception of the book. Around and through the Straits have flowed and coalesced many of the vitally important economic, social, political and cultural currents that have forged the character of this part of Southeast Asia, and influenced many other regions, both near and far. Along these sea-lanes came the Arab and Indian sailors and traders who met their Malay and Chinese counterparts here and gave the ports and cities of the region their distinctiveness. Gujerati merchants, traders sailing in Arab dhows, cargoes of textiles and woods came into the region in exchange for the spices and jungle products of the Peninsula. Chinese traders were equally adept at seeking both the trade goods and political loyalties of the emerging Malay and Sumatran states along the shores of the Straits.

Changes in patterns of trade and technology can also be read in the altered landscapes, cities, ports and hinterlands of these territories. The architects of European expansion—first the Portuguese, then the Dutch, later the English and French—saw the Straits as a key that would unlock the treasures of a mythical and mystical ‘East’. Controlling the precious commodities of the region—so many of which had to pass through the Straits—was the prize. The spices of the Mollucas, the jungle products of the interior, the precious metals (tin, gold, silver) of the hinterlands were to bring explorers, traders, merchants, colonists and, eventually, colonisation to the region. Whilst the importance of these external adventurers may properly, in the light of contemporary scholarship, have been lessened, the importance of that period’s influences on the institutions and physical form of the region remains strong. Whilst the power and preeminence of some of the great cities of the Straits—Aceh, for example, Srivijaya or Malacca itself—predated European impacts by many hundreds of years, other cities—Penang, or Singapore—owed much to colonial political and economic intervention. The particular balance—perhaps symbiosis would be a more appropriate term—between the indigenous and external is displayed in fields as diverse as built form, administrative structures, business methods, religious beliefs and rituals, and systems of social organisation. It is a diversity that owes much to the openness of the seas of the region and to the role of the Straits in funneling interchange of all kinds.

To what extent can our theme of unity be grounded in the historical and contemporary character of the Straits region? The French historian, Fernand Braudel (1975, I: 276), once wrote of that great inland sea, the Mediterranean, that it:

has no unity, but that created by the movements of men, the relationships they imply and the routes they follow…land routes and sea routes, routes along the rivers and routes along the coasts, an immense network of regular and causal connections, the life-giving bloodstream of the…region.

It is this notion of unity through movement and causal flows of goods, ideas and peoples that underlies our own conception of the Straits. Now the Straits are not the Mediterranean, nor, regrettably, do we have the skills of a Braudel. The seas here are much smaller, they are shallower and warmer and their hinterlands are much less extensive. But the role of the Straits is no less significant for that. The flows of people, goods, ideas, money, books, diseases, pollutants and ideologies have had an immense impact on the environments and peoples of the coasts and hinterlands that abut the Straits. As a seaborne world, these diverse elements share much of a common heritage, outlook and destiny. To examine them in this way is, we would argue, to remain true to their past history, their present character and their likely future.

THE STRAITS AS A UNIT

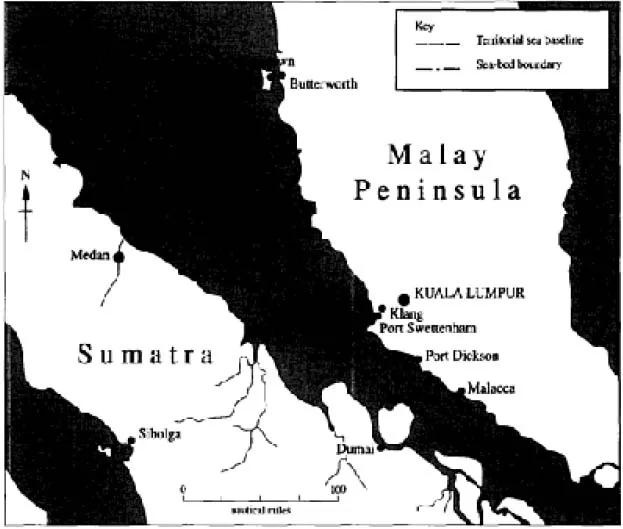

In terms of contemporary maritime law and navigation, the Straits of Malacca. per se can be said to extend from the sandbank known as One Fathom Bank opposite Port Klang at the mouth of the Klang River, through to Tanjong Piai and the island of Little Karimun at which point ships enter into the Singapore Strait, usually divided into the Durian Strait, the Phillip Channel and Singapore Strait proper. In strict navigational terms the Straits comprise those seas between a line to the northwest:

Figure 1.1 The Straits of Malacca in their regional context.

…from Ujung Baka (5.40 N, 95.26 E), the northwest extremity of Sumatra to Laem Phra Chao (7.45 N, 98.18 E), the South extremity of Ko. Phukit, Thailand.

and to the Southeast:

…from Tanjung Piai (1.16 N, 103.31 E), the south extremity of Malaysia, to Pulau Iyu Kecil (1.11 N, 103.21 E), thence to Pulau Karimum Kecil (1. 10 N, 103.23 E), thence to Tanjung Kebadu (1.106 N, 102.59 E). (Hamzah, 1997, 1)

Figure 1.1 shows the geographical situation of the Straits within Southeast Asia and Figure 1.2 the basic boundary units of the Straits themselves. As we shall see in a later chapter, issues of territorial sea boundaries, traffic separation schemes and marine safety requirements are complex and politically sensitive.

The Straits are essentially funnel-shaped, opening out to the Andaman Sea and Indian Ocean to the north and tapering to the southeast, through the Singapore Straits, before opening into the South China Sea. At the wide western entrance, the depths range from 34 to 84 m, but depths diminish to only 18 or 19 m close to the Aruah Islands. Further south, off Port Kelang, are a series of shoals and sandbanks, including One Fathom Bank where depths can be as low as 10 m.

Figure 1.2 Boundaries in the Straits of Malacca.

Depths increase again into the Singapore Straits though here the navigable channels are narrow (Chia and MacAndrews, 1981, 252–254).

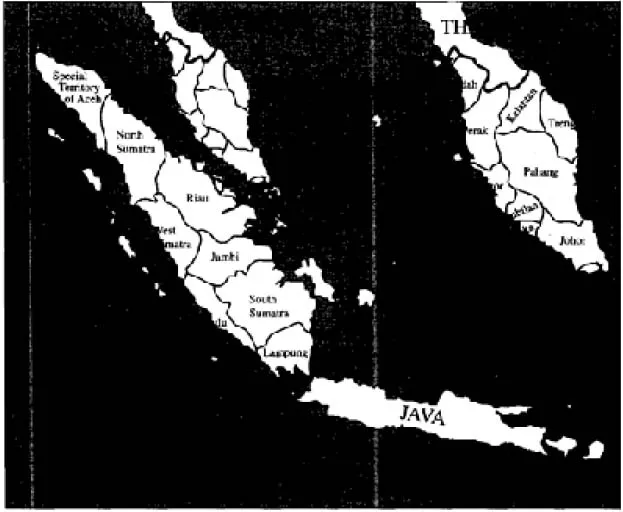

For the purposes of this book we adopt a broader view of the Straits which reflects the historical rather than contemporary nature and divisions of the region. The Straits take their name from the ancient city of Malacca (Melaka in the Malay), founded in the early fourteenth century, but which can be seen as one and the latest in a line of coastal settlements fronting the Straits which developed along the trading routes between India and China. For probably two thousand years, ships and traders from India and China had been travelling the Straits—buying and selling goods which could be traded on to more distant markets. Those ports and cities that developed along the Straits thus shared common economic characteristics and shared too an openness to outside religious, cultural and political ideas. Our concept of the Straits is thus much wider than a purely navigational one, although clearly navigation is at its heart. We argue that the coast and hinterland of northern Sumatra and the key city of Acheh (henceforth Aceh), together with the east coast of Sumatra down to Palembang as well as coastal southeast Sumatra have fallen, and continue to fall, within the cultural, political and economic orbit of the Straits. To the east of the Straits, Penang island and Perak, coastal Selangor and Port Klang, the port of Kuala Lumpur, together with Melaka (henceforth Malacca), Johor and Singapore can be seen as part of a cultural region which extends well beyond the narrow confines of the Straits themselves but which was intimately shaped by the flows and movements along that waterway. In terms of contemporary administrative boundaries, our region comprises Aceh, North Sumatra, Riau and Jambi in Indonesia, Perlis, Kedah, Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Malacca and Johor in Malaysia and the Republic of Singapore (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Administrative divisions in the Straits region.

The elements that make up this culture region are varied. In terms of environment and ecology the lands around the Straits share many similarities. The tropical climate with a relatively short monsoon period, a low-lying, mangrove-fringed coast (especially on the Sumatran side) and, most importantly, a regime of winds which has played a vital part in determining the nature and rhythms of navigation through the Straits, are amongst features shared by the region. Relatively shallow, warm coastal waters have provided a range of fishing and collecting opportunities to local peoples. The coastal area itself has proved difficult to settle. It is low lying and susceptible to considerable variations in lowtide levels, which has accentuated the importance of riverine locations as the prime sites for the port towns and cities which have given the region its character. Relations between the coast and interior have always been important. In both Sumatra and Malaya, significant indigenous groups in the interior such as the Batak or orang asli have long traded with coastal peoples. The juxtaposition of these two ecological and cultural zones no doubt further underpinned the attractiveness of the Straits to foreign traders and merchants.

Given the similarities in habit and habitat on both sides of the water, it is hardly surprising that there is a strong unity of cultural traits and ways of life in areas which, since the early nineteenth century have been politically cut off from each other. Those common traits are especially evident in the historic period. Strong similarities in the forms of the Malay language, the dominance of Islam, the continued survival of animist beliefs in the interior and traditions of legal and cultural structures which may owe much to Indian (especially Hindu influences) lend credence to an approach which seeks to see the region as one, drawn together by the common historical experience of using the Straits as a means of livelihood.

Although now formally separated by colonial and post-colonial political settlements, the territories on each side of the Straits still share much. Most striking is a common interest in the use and management of the Straits. Issues such as legal boundaries, navigation rights, traffic separation, piracy and pollution are pressing international issues. Huge tonnages of ships continue to pass through the Straits, drawing on both international markets (most notably in hydrocarbons), and on local and regional feeder ports. At the heart of this traffic, the city state of Singapore plays a pivotal role in both stimulating and controlling sea-traffic through the Straits. And, just as in the past, international interests in passage through the Straits are vital. Over three-quarters of all Japanese oil imports pass through the Straits, giving that major global power enormous vested interests in a range of maritime issues in the region. Equally, as the economic power of Southeast Asia has grown, passage through the Straits has assumed ever greater importance. For the ports of the region, as well as for their dependent hinterlands, the narrow, crowded sea-lanes represent, much as they did in the past, a key to economic growth and to political co-existence, cooperation and stability.

THE STRUCTURE OF THE BOOK

The approach taken by the book has determined its structure, and the treatment is both thematic and chronological. Part 1, The shaping of the environment, seeks to outline the important geological, morphological and ecological characteristics of the region. It is our contention that without an appreciation of these elements it is difficult to sustain the arguments made about the essential unity of the region. An understanding of the nature of the sea-bed, the characteristics of coastal erosion and accretion, the ecological character of the coastal zone, and the physical structures of coast and hinterland is vital if we are to understand the myriad ways in which human groups—both indigenous and foreign—have exploited, managed or altered those environments to their own ends. To this end, Chapter 2 examines the geological, oceanographic and geomorphological character of the Straits region, and Chapter 3 considers the key hydrological, ecological and climatic features that have impacted on human settlement and growth in the area.

The relationship between the physical and cultural environments of the Straits has always been a highly dynamic one. Techniques of exploitation and management change from one society and one time period to another, and those changes can give important insights into how the environments of the region were perceived, evaluated and utilised. These changing resources and techniques are the subject of Part 2, Resources and techniques. In Chapter 4, we examine the range of resources of the region—soil, biotic and aquatic—and consider how use of those resources has transformed settlement and economy in the region. Important issues of resource management are also raised here as a prelude to a more detailed examination in a later chapter. In Chapter 5, some of the key relationships between technology and the use of the Straits are considered. In a region such as this, long wedded to international maritime trade, changing shipping technology has been crucial. The arrival of technologically advanced European vessels in the fifteenth, the invention of the steam ship in the nineteenth, or the development of new techniques of containerisation or bulk transport in the twentieth century, all wrought important changes in the human geography of the Straits region.

In Part 3, Collective histories, these varied threads—environment, technology, human settlement and use of resources and political evolution—are drawn together in a chronological examination of the historical geography of the Straits region. The central importance of maritime trade underpins each of these chapters. Chapter 6 examines the important pre-European polities in the region from Srivijaya and Malacca to Aceh and Johor, and considers the role of both short- and long-distance trade in shaping the character of these important settlements. Chapter 7 focuses on the wider impact of European intervention in the Straits from the arrival of the Portuguese off the city of Malacca in 1511 to the rise of Singapore as a global port by the late 1920s.

Part 4, Collective opportunities, examines the likely impacts of contemporary development on the varied human and physical environments of the Straits. Chapter 8 considers the patterns of political and economic development since the end of the Second World War, a period marked by high growth rates, the increasing impact of environmental change, and the growth of trade in both goods (from hydrocarbons to refrigerators) and people (from legal and illegal migration to the impact of international tourism). As economic growth, mass tourism and urban redevelopment reshape the region, Chapter 9 considers the likely effects of increased economic cooperation between the countries of the Straits on its future. As ASEAN (the Association of South East Asian Nations) seeks to increase cross-border cooperation amongst its members, is greater cooperation in environmental and economic matters going to result in changes to the management and future development of the region? Chapter 10 examines this issue further in relation to a range of important environmental issues that affect the Straits such as waste management, pollution, toxic waste and the law of the sea.

What we are seeking to do in this book is to provide a context within which to understand the shape, character and evolution of a distinctive and important region of the world. Our treatment is not novel a...