1 Diversity and Development in Asia and the Pacific

INTRODUCTION

The main objective of this chapter is to show the spread of and diversity within the region in terms of geographic and demographic features and development indicators. Some of the main variables discussed are the Asia-Pacific region and sub-regions within it, socio-cultural diversity, political systems, governance and corruption, economic diversity, poverty, peace and conflict, health, environment, disasters, gender parity, indigenous populations and ethnic minority groups, the use of information technology, the urban rural divide, and development aid. The final section critically discusses the interaction between the region’s diversity and development issues.

THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION AND ITS SUB-REGIONS

The geographical description of the Asia-Pacific region is not uniformly specified in the literature, as naming and drawing political borders on the physical geography is often controversial and contested. The Asia-Pacific region contains two continents, Asia and Australasia, and over one-third of the earth’s surface. Its land mass extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north, in the west, from the Ural Mountains, the international boundary between the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan, the western shore of the Caspian Sea, the Caucasus and the northern shore of Black Sea, in the south the Indian Ocean, and, in the east the Pacific Ocean. Its total land area is 53,857,454 square kilometres or 20,794,478 square miles. A look at the physical geography without political borders of the region reveals mountain ranges, forests, long coastal lines, lakes, unbroken rivers, massive snowfields and deserts, and small and large islands. The region is very rich in natural resources such as petroleum, minerals, forests, fish and water. However, the reality is that there are political borders and nation states, and these natural resources are unevenly spread within those political borders, thereby placing some nation states in a much better position than others. In some respects, these natural resources are underlying causes of conflicts, war and violence between nation states.

In terms of population, the Asia-Pacific region is also rich in human resources, though these need to be better developed. It is home to approximately three-fifths of the world’s population. In 2000, the region had 3,678 million people, by 2025 the number is expected to increase to 4,819 million, and it has been projected that, by 2050, the region will have 5,432 million people (Philip’s Atlas of the World 2006). By considering the potential of emerging economies of China and India and overall growth rates of other countries, the significance of the region in the world has been well recognized. However, over half of the world’s extreme poor (641 million) live in the region, and the number could be much higher if we consider the impact of the recent inflation in food prices (ADB 2008a). About 50 percent of the region’s population (1.7 billion people) is poor, with their income is less that $2 per day. Extreme levels of poverty and the need for significant poverty reduction, particularly in South Asia, are the major challenges for the region.

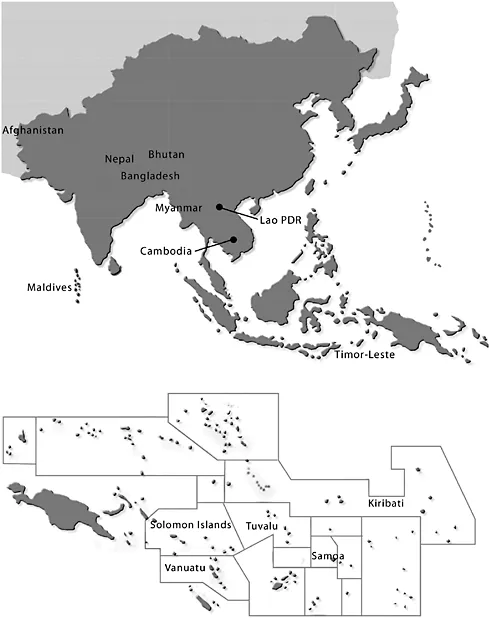

According to the geographic spread, the region has been classified into several sub-regions, but there is no uniformity or consistency in the classification and nomenclature of sub-regions and the number of countries included in the sub-regions. This non-uniformity and inconsistency in classifying the sub-regions may be attributed to authors’ and organizations’ interests and objectives. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) classifies its developing member economies into East Asia (China PR, Hong Kong, China, Korea R, Mongolia and Taipei, China), Central and West Asia (Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), the Pacific (Cook Island, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu), South Asia (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka) and South East Asia (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam). Some countries in the region are classified as least developed, land locked and small island states (UN OHRLLS 2008). Based on development indicators, fourteen countries are grouped under least developed countries. Of these, four are land locked (Afghanistan, Bhutan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Nepal), three are on coastal land (Bangladesh, Cambodia and Myanmar) and the remaining are small islands (Kiribati, Maldives, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Tuvalu and Vanuatu). ESCAP (2007a) has developed two broad development categories within the region—developed and developing economies or countries. Developed economies include Australia, Japan and New Zealand. Further, it has grouped developing countries under five sub-regions as presented in Table 1.1. This book mostly follows the ESCAP’s sub-regions as their data are analyzed according to those regions.

Table 1.1 Sub-regions of Asia and the Pacific (includes only developing economies)

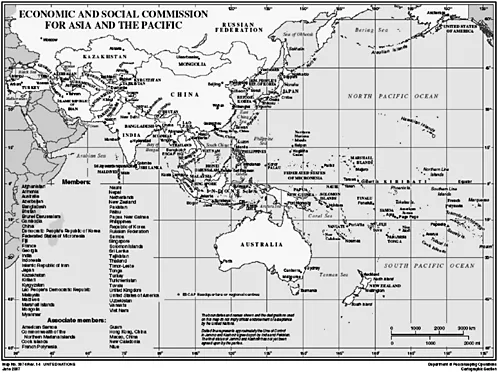

Figure 1.1 Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Source: The UN Cartographic Section, ESCAP, no. 3974 Rev. 14, June 2007

Figure 1.2 Location of least developed and landlocked countries in Asia and the Pacific. Source: UNDP (2005, X).

Irrespective of sub-regions, most of the developing countries in the region are commonly characterized by low income, low levels of living, poor health, inadequate education, low productivity, high rates of population growth, substantial dependence on agriculture and primary-product exports, imperfect markets, and vulnerability (see Todaro and Smith 2003). Likewise, the region’s least developed countries are generally characterized by a persistently high level of poverty, a large rural based population, an economy heavily dependent on agriculture, poor infrastructure, vulnerability, a high level of under-nourishment and a significant resource gap (FAO 2003a; UNDP 2005). Asia-Pacific countries are also diverse in terms of historical legacies, size, geography, resources, population, income, ethnicity and religion, industrial structure, external dependence and influences, and power, political and institutional arrangements (Todaro and Smith 2003). Some of these and similar diverse features are briefly discussed below.

SOCIO-CULTURAL DIVERSITY

Culture is comprehensive and all encompassing. Scott (1998) quotes Alfred L. Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn’s conclusion that “culture consists of patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behaviour acquired and transmitted by symbols, constituting the distinctive achievements of human groups, including their embodiments in artifacts; the essential core of culture consists of traditional (i.e., historically derived and selected) ideas and especially their attached values.” Many villages of the Asia-Pacific region have, to some degree, their own history, ideas, artifacts and values, and thus the region bubbles with cultural richness and diversity. Looking at the socio-cultural diversity at sub-regional and country levels may not make much sense as varied beliefs, values and practices are often deep rooted at the micro level, making it a most complex phenomenon for outsiders to understand. Two examples will suffice to demonstrate the socio-cultural diversity in the region. The first is language as a symbol of culture and means for communication. People communicate their way of life, values and beliefs, and customs through approximately 3,500 languages. Further, there are thousands of dialects that may or may not have a written script. The second is religion which is often one of the major sources of education and the development of values. All major religions are popular in the region, and religions cut across the Asia-Pacific sub-regions. For example, most1 of the people in Cambodia, Japan, Lao PDR, Mayanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam follow Buddhism. In China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore, Chinese indigenous religion (Taoism, Buddhism and Chinese folk religion) is also popular. The majority of people in Australia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Philippines and Russia follow Christianity. Hinduism is followed in India and Nepal. Islam is the most popular religion in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan (O’Brien and Palmer 1993). Importantly, indigenous people across the region also have their own belief systems. Beyond religious diversity, within religions there are thousands of sects and castes (e.g. in India). Generally, a sense of belonging and identity stems from languages and religions, which often also have been sources of communal tension and conflict in some pockets of the region (e.g., in Afghanistan, India, Sri Lanka, Philippines, Thailand and Tibet). Religions also appear to significantly influence political dynamics, voting patterns and connections to power. Do religions have any role in community development, especially where people hold traditional beliefs? Commonsense suggests that culture and cultural diversity are crucial to community development practice. Community development endeavors in the region need to dovetail with the cultural diversity in communities and yet will also contribute to the broader culture that focuses on overcoming cultural practices that are prejudicial along class, race and gender lines.

POLITICAL SYSTEMS

Although political systems in the Asia-Pacific region are diverse, they are the fundamental bases for good governance and value-based community development practice. They also determine the method of electing or selecting leaders and making decisions. A sound political system is essential for good community development practice. Many countries’ political systems are rooted in their historical legacies of colonization. Except for China, Japan and Thailand, all countries and islands in the region were colonized by other countries, notably United Kingdom, France, Portugal, Netherlands, Germany, Japan, China and former Russia. Almost every country has struggled hard to gain independence from the colonizer(s), and each has established statehood. Without mobilizing people and their communities, this achievement would not have been possible. Despite diverse political systems, the same mobilization is needed to resolve internal issues facing countries today at the grassroots community level.

Depending upon the political system, governance structures and freedoms enjoyed by people in the region greatly differ. In the Asia-Pacific region, 58 percent have parliamentary systems and the remaining 42 percent have monarchies or one-party states (UNDP 2008, 27). China, DPR Korea, Lao PDR and Viet Nam are communist states. However, China has significantly decentralized and introduced elements of democracy at grassroots levels, both in urban and rural areas. In Myanmar, a military junta dictates the terms. Hong Kong and Macao enjoy only limited democracy. Mongolia follows a mixed parliamentary and presidential system. In South Asia, most of the countries are federal republics or parliamentary democracies. Through the process of decentralization, India has provided significant power and resources to local level governing systems. Bhutan has recently transitioned from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy. Afghanistan is under an Islamic republic system. Many East Asian countries have the background of dictator rulers, but now have changed to different variations of constitutional monarchy (Cambodia, Brunei, Malaysia and Thailand) or to parliamentary republic systems (Indonesia, Philippines and Singapore). Although newly formed Central Asian countries are republics, most of them have authoritarian presidential rule. In Australia and New Zealand and six Pacific islands, a parliamentary democratic system is followed. At least most of the time, Fiji, Vanuatu, Kiribati and Nauru have republic governments. Nine Pacific islands are under the administration of western governments with local governing systems (e.g., New Caledonia and French Polynesia under France; Guam, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Northern Marina Islands, Palau and American Samoa under the United States; and Cook Islands under New Zealand).

In many countries of the region, such as Fiji, Afghanistan, Myanmar, East Timor, Indonesia, Nepal and Solomon Islands, political systems and governments are unstable and struggling. In 2007, ten of the Asia-Pacific countries were listed as fragile states2 by the World Bank’s International Development Agency. Although political systems and governments are relatively stable in India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Thailand, and the Philippines, frequent insurgencies and ethnic conflicts are common in some parts of these countries. Most Asian countries face significant governance issues.

GOVERNANCE

Irrespective of diverse political systems, what matters for development is their quality of governance. Governance has been identified as an important factor in ensuring the achievement of development goals and the development and prosperity of societies.

Important elements of governance include the political institutions of a society (the process of collective decision making and the checks on politicians, and on politically and economically powerful interest groups), state capacity (the capability of the state to provide public goods in diverse part of the country), and regulation of economic institutions (how the state intervenes in encouraging or discouraging economic activity by various different actors). (Acemoglu 2008, 1)

Asia-Pacific countries’ political institutions, capacity to provide public goods and regulatory mechanisms significantly differ, ranging from weak to somewhat good. But poor countries in the region seem to have similar governance issues. Grindle (2002) states:

Almost by definition their (poorest countries’) institutions are weak, vulnerable, and very imperfect; their public organizations are bereft of resources and are usually badly managed; those who work for government are generally poorly trained and motivated. Frequently, the legitimacy of poor country governments is questionable; their commitments to change are often undermined by political discord; their civil societies may be disenfranchised, deeply divided, and ill equipped to participate effectively in politics.

Corruption is one of the important governance issues as it has been argued that it is closely connected to poverty levels, weak implementation of development programs, and inadequate and inappropriate delivery of humanitarian assistance in disaster affected areas (World Bank 2002a; 2006a; TI 2006). Does this have any implications for people’s participation and community development? According to Transparency International’s (TI 2006) corruption perception index, 23 Asia-Pacific countries’ score ranged from 1.9 to 3.6 (10 is highly clean and 0 is highly corrupt), which indicates the diversity and severity of the perception of corruption in these countries. Myanmar was second last on the list with a score of 1.9 (See Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Corruption Perception Index 2006

The analysis of peoples’ ratings (1 is not corrupt and 5 is highly corrupt) of various sectors in Asia-Pacific suggested that politicians (rated 4) were the most corrupt group followed by police (rated 3.8), legal system (rated 3.3) and educational system (rated 3.1) (UNDP 2008, 47). The inefficient and ineffective creation and delivery of public goods hamper the development process and diminish people’s faith in their own governance systems. Governance issues in all Asia-Pacific countries significantly impact the whole population, particularly the poor.

Another important issue in good governance is the country’s ability to control corruption in various sectors—judiciary, health, education, public infrastructure building and social welfare services (see UNDP 2008). In many countries (e.g., Bhutan, India and Indonesia) political leaders have begun openly discussing the issue of controlling corruption, and twenty-eight countries in the region now have anti-corruption agencies, though their effectiveness in controlling corruption varies significantly. With some exceptions and without any conclusive evidence, perception studies have pointed out that countries with democratic and parliamentary systems have better control of corruption (UNDP 2008, 26–29) and presidential and semi-presidential systems have more perceived corruption.

From Table 1.2, it may be inferred that, as high levels of a perception of corruption are mostly located in developing and least developed countries, poor governance and poverty levels are linked (World Bank 2006a), with many poor countries having weak governance structures. Although a lot has been written on poor governance and poverty, whether poor governance leads to high levels of poverty, or poverty leads to poor governance is not clear. As governance is not one factor, but a combination of several factors in unique countries’ contexts, any sweeping generalizations and prescriptions would be unwarranted (see Grindle 2002). Recent research suggests that “there is a correlation between ‘good governance’ and the level of development (per capita GDP), but there is no correlation between it and the speed of development (medium-to-long-term growth)” (Meisel and Ould Aoudia 2007). That means attaining good governance does not quickly result in low levels of poverty; indeed it seems to be a gradual long-term process. Grindle argues that “good governance is deeply problematic as a guide to development”.

ECONOMIC DIVERSITY

Economic diversity in the region is obvious. As stated above, several countries have been classified into developed, developing, least developed, land locked and small island states. Economically well-developed societies do not always represent peaceful and progressive societies. Progress may create and contribute to problems in these communities (e.g., drug addiction, mental health issues and neglect of poverty) as well as to problems in other communities beyond the national borders (aid with political motivations, funding conflict, out-sourcing, etc). Although economic growth for all developing economies of the region appears strong, the rate is expected to fall from 8.2 in 2007 to 7.7 in 2008, and there have been further significant declines in 2009 with the international credit and financial crisis. A similar declining trend may be seen for all the subregions of the Asia-Pacific, except Pacific islands economies (see Table 1.3) experiencing increasing inflation beyond the forecasted rate. Due to the recent economic bailout packages and their impact, the inflation figures presented in Table 1.3 may significantly change showing further higher inflation. The forecasted economic growth rate in the region for 2008 ranged from 0.8 percent for Tonga to 25 percent in Azerbaijan. China and India, with 10.7 and 9 percent growth rates, respectively, were and will be major economic drivers in the region. The inflation rate ranged from 0.4 in Japan to 16 in Azerbaijan and Iran. Globalization and trade liberalization appear to be driving forces of economic development, and many countries in the region seem to have no choice but to follow that path. ADB’s 2020 strategy states that

Table 1.3 Sub-regional Rates of Economic Growth and Inflation in the ESCAP Region, 2006–2008

by 2020, the Asia-Pacific region could move to a higher level of economic development. Asia’s share of global exports has soared from 16 percent in the 1980 to 27 percent today. It has the largest reserves and the highest savings rate in the world. By 2020, the region could account for one third of world trade. Its share of global GDP in nominal dollar terms could double to almost one quarter—or as much as 45 percent in terms of purchasing power parity. Perhaps 90 percent of its people could be living in countries that have achieved middle income status, mostly in mega cities and urban areas. As growth continues, however, it may become increasingly difficult to reach those who remain excluded from its benefits, even though absolute poverty could be reduced to as little as 2 percent of the total population. (ADB 2008b, 1, 5)

POVERTY AND INEQUALITY

These figures suggest that, although economic growth figures in the region are impressive, such is not the case with poverty figures, which have been persistently high in the region for a long time. As stated earlier, over half of the world’s extreme poor (641 million) live in the region. The analysis of the progress of Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) shows that, on the whole, the Asia-Pacific region was, in 2006–2007, on track, making good progress towards eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, and expected to achieve this goal by 2015. But least developed countries in the region, with a 34 percent poverty rate, are making slow progress and may not be able to eradicate poverty by 2015. The magnitude of poverty in China and India is a major challenge. Measured against the US$2 per day mark, over 450 mill...