![]()

Part I

Stylised facts and literature

review

![]()

1 Stylised facts on foreign direct

investment inflow to China and

its spillovers

Stylised facts on FDI in China

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is the movement of capital across borders in a manner that grants the investors control over the acquired assets. FDI is different from portfolio investment in that the latter does not offer such control. There are two forms of FDI – greenfield investment which initiates direct investment in new assets; and mergers and acquisitions in which a foreign firm acquires part (or all) of the assets of an existing host firm. Firms that conduct FDI activities are called multinationals enterprises (MNEs) or transnational corporations (TNCs). FDI plays an increasingly significant role in the global economy.

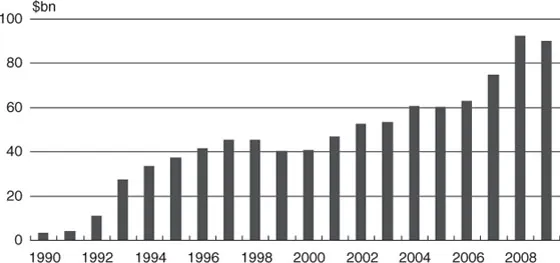

In the late 1970s China ended its isolation from the outside world and began to implement a “reform and opening-up” strategy. With its enormous labour supply and low labour cost (Ceglowski and Golub 2007), stable political and economic environment, and pro-FDI policies, China has become an attractive FDI destination. As a result, FDI inflows1 to China increased dramatically from US$0.9 billion in 1983 to $90.0 billion in 2009, as shown in Figure 1.1.

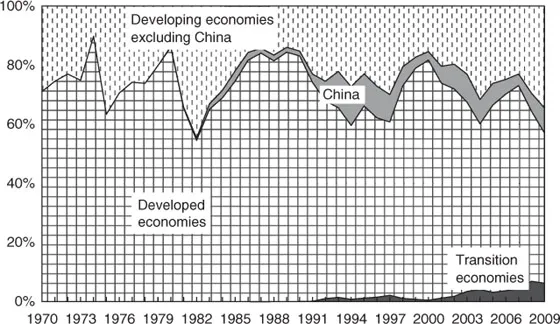

Since 1993, China has been the largest FDI recipient among the developing countries, and in 2003 it was the largest FDI recipient in the world. In 2009, China was still the world's second largest destination for FDI, the United States being the largest. Since the majority of FDI flows into developed countries (see Figure 1.2), it is amazing that China, as a relatively backward country, holds such a strong attraction for foreign capital.

More than 95 per cent of the FDI in China falls into one of the following three entry modes (see Table 1.1):

(1) Solely foreign-owned enterprises that are exclusively invested in and owned by foreign companies, enterprises, and other economic organizations or individuals;

(2) Joint ventures that are joint investments by foreign companies, enterprises, and other economic organizations or individuals and Chinese companies, enterprises, and other economic organizations. The latest Law on Chinese-Foreign Joint Ventures (2001) states in Article 4 that “the proportion of the investment contributed by the foreign partner(s) should not be less than 25 per cent of the registered capital of a joint venture”;

Figure 1.1 FDI inflow to China, 1990–2009 (US$ billion).

Note: Here and throughout this book, current prices are quoted unless otherwise stated.

Source: China Economic Information Network (http://www.cei.gov.cn/).

Figure 1.2 FDI inflows, global and by group of economies, 1970–2009.

Source: UNCTAD Database (http://unctadstat.unctad.org/).

(3) Cooperative enterprises that are established based on cooperative terms and conditions agreed upon by foreign companies, enterprises, and other economic organizations or individuals and their Chinese counterparts.

As for the sources of FDI, East Asia and Southeast Asia have contributed more than 60 per cent as of 2009, as shown in Table 1.2. However, the FDI stock from East Asia and Southeast Asia only accounted for 12 per cent of world total outward FDI stock as at the end of 2009, while the outward FDI from Europe and North America accounted for 80 per cent of world total outward FDI stock (see Figure 1.2).

Table 1.1 FDI entry modes, 1978–2009

| Signed contracts | Actual FDI |

| Number | Per cent | Amount ($bn) | Per cent |

Solely foreign-owned | 335,908 | 49.2 | 526.8 | 54.8 |

Joint ventures | 287,184 | 42.0 | 301.6 | 31.4 |

Cooperative enterprises | 59,556 | 8.7 | 98.9 | 10.3 |

Other types | 557 | 0.1 | 34.0 | 3.5 |

Total | 683,265 | 100.0 | 961.2 | 100.0 |

Source: as Figure 1.1.

Table 1.2 Top 10 sources of FDI in China, 1978–2009

| Actual FDI |

| Amount ($bn) | Per cent |

Hong Kong | 394.6 | 41.1 |

Virgin Islands | 101.0 | 10.5 |

Japan | 69.3 | 7.2 |

United States | 62.1 | 6.5 |

Taiwan | 49.5 | 5.1 |

South Korea | 44.5 | 4.6 |

Singapore | 41.2 | 4.3 |

Cayman Islands | 19.1 | 2.0 |

United Kingdom | 16.3 | 1.7 |

Germany | 16.3 | 1.7 |

Others | 147.6 | 15.4 |

Total | 961.2 | 100.0 |

Source: Investment in China, Ministry of Commerce of China (http://www.fdi.gov.cn/); China Economic Information (http://www.cei.gov.cn/).

Note: Throughout this book, “China” refers to the People's Republic of China, i.e. mainland China, unless stated otherwise. In mainland China, direct investment from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan enjoys the same favourable treatment as FDI from other sources.

There are many factors leading to the unusually large-scale Asian FDI in China. “Chinese connections” constitute the first factor, including ethnic Chinese networks, similar languages and culture, and geographic proximity (Zhang 2005). Second is the perfect match between the relocations of export-oriented manufacturing sectors from Asia's newly industrial economies (due to their rising labour cost) and China's national strategy of export orientation. By transferring manufacturing centres to China, the resource-seeking FDI helps multinationals maintain their cost advantage in the international market (Deng et al. 2007).

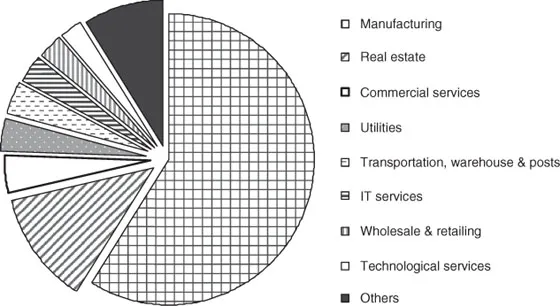

Figure 1.3 Industry distribution of contract FDI inflow in China, 2004–2009.

Source: as Figure 1.1.

In terms of industry distribution, 58 per cent of accumulated FDI flows to the manufacturing sectors in China (see Figure 1.3). This ratio is much higher than the proportion of manufacturing in China's total gross domestic product (GDP), which has remained within a relatively narrow band between 37 per cent and 44 per cent since 1978. By transferring manufacturing and assembly centres to China, FDI is viewed to have brought significant technology spillover to these sectors (Buckley et al. 2002, 2004, 2007a; Girma and Gong 2008a; Liu 2008).

Productivity spillover of FDI

One of the most important aspects of FDI is that it embodies advanced technologies and business practices which can be transferred to the host economies. Domestic firms can improve their productivity through their connections with MNEs. This externality is referred to as FDI “productivity spillover” or “technology diffusion” in the recent economic literature (Blomström and Kokko 1998; Görg and Strobl 2001; Görg and Greenaway 2004; Keller 2004). Productivity spillovers do not include contract-based transfer or illegal acquisition of intellectual property rights, know-how, or any kind of technology. Productivity spillovers are a relatively intangible and intractable phonomenon and can take place through four channels, namely, labour mobility, vertical linkages, export of MNE affiliates, and horizontal effects.

(1) Labour mobility. Employees trained by MNE affiliates will benefit from the production knowledge and management expertise they have acquired after they return to domestic firms or establish their own enterprises (Fosfuri et al. 2001; Görg and Strobl 2005; Markusen and Trofimenko 2009).

(2) Vertical linkages. MNE affiliates help upstream and downstream domestic firms to set up production facilities, providing them with technical assistance and management and organization training. Besides, the presence of MNEs may also trigger competition among upstream and downstream firms (Markusen and Venables 1999; Javorcik 2004; Girma and Gong 2008a; Girma et al. 2008).

(3) Exports of MNE affiliates. MNEs transfer and relocate their manufacturing centres to export-oriented economies which are relatively labour-abundant, e.g. China and Vietnam, and export assembled product to third markets. This can help domestic firms gain access to international markets and promote their productivity (Aitken et al. 1997; Clerides et al. 1998; Greenaway et al. 2004; Greenaway and Kneller 2008).

(4) Demonstration and competition. MNEs usually possess an advantage in technology (Dunning 1977, 1981; Markusen 2002b) and exert a strong demonstration effect on the domestic firms in host countries. In observing the market activities of MNE affiliates and competing with MNE affiliates, local firms can imitate MNE technology and make corresponding innovations (Koizumi and Kopecky 1977; Findlay 1978; Wang and Blomström 1992).

Productivity spillovers are not only beneficial to domestic firms in the host countries, but may also benefit the multinational affiliates by fostering a more productive economic environment in the host market.

Factors governing productivity spillovers of

FDI in China

The potential for the foreign capital inflow attracted by preferential FDI policies, low labour cost, and improved infrastructure to bring positive productivity spillovers to Chinese indigenous enterprises has been strengthened by the following factors:

(1) Freer labour market. During the process of marketisation, the Chinese government abandoned the life-long employment system, lowered the barriers between rural and urban areas, and gradually constructed a freer labour market (Knight and Yueh 2004). A variety of “new” ownerships emerged, such as foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) and private firms, which ended the dominance of state-owned enterprises. Employees are free to leave FIEs and set up their own private firms using the management techniques they have acquired during their work experience.

(2) Stronger linkages with FIEs. Upstream domestic enterprises have developed quickly in the past three decades and their product quality has improved. So FIEs in China are more willing to source locally from those qualified domestic firms, creating the opportunity for productivity spillovers via input–output linkages (Farrell et al. 2004; Long 2005).

(3) Learning to export by observation. The striking export performance of FIEs has provided examples for domestic firms to learn to enter overseas markets. They have also familiarised the world with Chinese exports. Both can effectively lower the entry cost of domestic firms’ exportation (Kneller and Pisu 2007).

(4) Increased but moderate competition. The competition caused by the increased foreign presence has stimulated domestic firms to improve their productivity and performance. At the same time, the competition in most industries is not so fierce as to force a mass exit of domestic firms. The Chinese domestic market is growing sufficently fast that domestic firms have the opportunity to find their own niche (Long 2005).

However, FDI productivity spillovers are neither free nor automatic. In fact, there have been debates over whether spillovers really occur, and if so, their magnitude. The following factors influence the size of ...