- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inflation and Unemployment

About this book

This work challenges traditional monetary theory by focusing on the role of banks and provides a new insight into the role played by bank money and capital accumulation. An international team of contributors reappraise analyses of the inflation and unemployment developed by Marshall, Keynes and Robertson. This volume is published in association with the Centre for the Study of Banking in Switzerland.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inflation and Unemployment by Mauro Baranzini, Alvaro Cencini in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

INFLATION AND UNEMPLOYMENT: A MONETARY AND STRUCTURAL FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS

1

INFLATION AND DEFLATION

The two faces of the same reality

INTRODUCTION

Economists are far from being unanimous about the nature of economic disequilibria and the way they should be dealt with. For example, according to the rational expectations school, money does not affect real variables both in the long- and short-run. Thus, changes in the money supply alter the general price level directly, leaving unchanged real variables such as employment, output and the real wage rate. Monetarists, instead, have always allowed for short-run real effects of monetary changes while claiming that in the long-run real equilibrium is not affected by monetary fluctuations. At the other end of the spectrum of suggested interpretations, we are faced with the claim that disequilibria arise essentially because of money. In a world of barter, as maintained by Shackle, total demand and supply are necessarily equal and ‘it is only when we introduce a substantive means of purchase, one which does not merely represent today’s products but exists or arises in its own right, outside the list of products,’ (Shackle 1967:91) that disequilibria are bound to appear. On the whole, the core of the dispute among economists is represented by the role attributed to money as a possible cause of inflation and unemployment. According to neoclassical tradition, real variables are all that matter and money is a kind of veil which can only momentarily affect the real world. The neoclassical perception of the economic system is essentially dichotomous and the theory lacks a satisfactory solution to the problem of money integration. Having mainly taken over the neoclassical approach, Monetarists develop their analysis assuming that economic agents can only momentarily be fooled by a change in the monetary stock. In the long-run expectations are adjusted to take nominal variations into account so that real variables are no longer influenced by the initial increase (or decrease) in the money supply. On the contrary, Keynesians have traditionally put money at the centre of their analysis, emphasising the role of interest rates and income distribution in the evolution of inflation and employment. Yet, despite their global monetary approach, Keynesians develop their theories in terms of equilibrium between demand and supply and are thus led to analyse the anomalous working of the system from the behavioural point of view. This ‘behavioural’ approach is so deeply rooted in monetary economics that even an economist such as Goodhart does not hesitate to claim that, although ‘the institution of money provides the information network which enables a complex, decentralised economy to function at all’ (Goodhart 1975:194), it is the economic agents’ irrational behaviour which is to blame for economic instability. ‘Because money is a necessary adjunct to such an economy, the disequilibria in the economy are sometimes regarded as monetary phenomena; it is, however, the inconsistency of decisions within the system, not the existence of the monetary framework, which is the proximate cause of disequilibria’ (p. 194).

The aim of this chapter is to provide an alternative approach to inflation and unemployment starting from the logical rules governing bank money. It can hardly be doubted today that our economic systems are based on the use of money and that money is essentially of a banking nature. Any serious attempt to explain both inflation and unemployment has to start from this state of affairs and must consistently account for the integration of money into the real world. In order to show that economic disequilibria are neither caused by behavioural nor real factors, we shall first lay down the principles of a monetary economy by referring to the quantity theory of money. Correctly re-interpreted and secured against the devastating consequences of the neoclassical dichotomy, this theory can in fact provide the basis for a new analysis of economic reality in which money is no longer an exogenous variable. Having done this we shall then apply the principles of bank money to the traditional explanations of inflation and unemployment. This exercise will allow us to show that they all fail to provide a satisfactory answer to these problems since they rest on a truncated perception of the workings of our monetary systems. The same conclusion applies to the reiterated attempt to establish an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment. As confirmed by factual observation, these two disequilibria are not independent of each other, yet the simultaneous presence of inflation and deflation is a reality which has been out of the reach of theoretical explanations so far. Finally, in the last section we shall outline the main features of a theory in which economic disequilibria are traced back to a formal anomaly due to the imperfect correlation existing today between the monetary structure of our systems and the laws of bank money.

THE QUANTITY THEORY OF MONEY: A REAPPRAISAL

According to the standard version of the quantity theory of money, an increase in the money supply leads to a proportionate increase in the level of prices through the real balance effect. This mechanism, introduced by Patinkin in his Money, Interest and Prices (1969), is based on the idea that, following an increase in the quantity of money made available in the economic system, consumers will attempt to finance extra purchases of goods out of their money holdings. Although the increase in the money supply cannot alter the real demand for goods, the real balance effect seems to provide an explanation as to how a monetary disequilibrium can generate a change in the level of prices, the main argument being that increased money balances allow for an increase in the desired demand for goods. Hence, though consumers cannot increase their real purchases of goods, their increased desire for them has the effect of raising their prices.

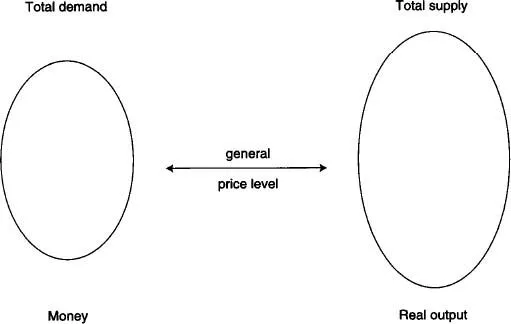

It is hardly necessary to stress that this attempt to conciliate the traditional neoclassical analysis elaborated in real terms with the quantity theory of money can no longer be seriously taken into consideration. No one doubts that a desired demand is only a virtual force with no power of altering prices at all. Whatever my desire to buy a Rolls Royce, the demand for Rolls Royces does not vary in the least unless I can effectively exert it. Moreover, the neoclassical dichotomy between real and monetary variables can only be disposed of by integrating money into the real world, which means that the distinction between real and monetary demand for goods is farfetched. In today’s economic world the real demand for goods is exerted in monetary terms and any serious theory must account for this. The Monetarist starting point is the neoclassical theory of relative prices determination. Money is brought into the picture as a net asset issued by monetary authorities and demanded by the public in order to satisfy its needs for a means of exchange and a store of value. Hence the price of this new and peculiar object called money is determined, like that of any other real good, through the adjustment of its supply and its demand. Unlike single real goods, however, the price of money is determined taking into account the whole of produced output, i.e., the whole amount of goods which must be bought by money. ‘Thus the general price level can be reduced to a relative price, the relative price of money and the composite commodity’ (Flemming 1976:9). Whereas the supply of money depends on the activity of emission carried out by the banking system, the demand for money is finalised to the purchase of goods and services, and in a system of general equilibrium corresponds to the supply of real output. In the same way as in a two commodity world the supply of a defines the demand for b and vice versa, in a monetary system the supply of real output is identical to the demand for money. The determination of the general price level is thus obtained through the adjustment of two distinct masses: the mass of money and the mass of real output (Figure 1.1).

This representation corresponds to the traditional version of the quantity theory of money where, according to the assumption that the level of output is independent of the size of the money supply, money is exogenously determined. Now a question can be raised here about the hypothetical exogeneity of money in a world where money is entirely of a banking nature. If banks, whether central or secondary, were to exogenously provide the economy with the quantity of money required to carry out transactions, monetary stability could be granted only by a strict control over the growth of the money supply (determined by the banking sector) relative to the growth of real output (determined by the real sector). A thorough analysis of modern bank money shows, however, that what can effectively be issued by banks is a purely numerical vehicle with no intrinsic value whatsoever. As a matter of fact, the Classics were already aware of the necessity to distinguish (nominal) money from income (real money), and economists have always implicitly refused to consider money as a net asset since they have never added the value of money to that of output when determining national wealth. Their acceptance of the equality of national income and national output is perfectly in line with Smith’s claim that money and output are the two faces of one and the same object. Modern banking confirms this. The emission of money is, first of all, an operation through which banks provide the economy with a numerical standard. In order to fulfil this task banks only need to enter the economy in their bookkeeping, an operation which, as such, does not require the presence of any real asset. Corresponding to the opening of a line of credit in favour of the economy, the emission of vehicular money becomes operative as soon as firms take advantage of it to cover their costs of production. At this moment money is so strictly associated with real output as to become its alter ego. Bookkeeping entries in the banking system reveal the nature of this relationship. Let us consider the payment of wages (direct and indirect) made by a secondary bank whatsoever, B, on behalf of firm F (Table 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The general price level, the mass of money and the mass of real output

Having incurred a debt to the bank, firm F is entered on the assets side of B’s balance sheet, while producers, being net creditors towards the bank, are entered on the liabilities side. The payment carried out by B corresponds to the monetisation of production and gives rise to a new income. Because of this payment vehicular money is transformed into a net asset initially owned by workers and then, once transfers have been taken into account, by final income holders. But what about real output? How is the relationship between money and goods established? The answer is straight-forward. Having asked the bank to carry out the payment of workers on its behalf, firm F is indebted to B and the object of its debt (the very income earned by W) has the real output as its content. In other words, the goods produced by W are momentarily deposited with F (which cannot be their final holder since it is indebted to B) but they are effectively owned by the income holders who, having a net credit to B, have at their disposal the drawing right (purchasing power) over current output. Hence, through the monetisation of production, real output acquires a monetary form and is transformed into a given amount of income of which it is the real content. Money and output are thus the two sides of the same reality, and not two distinct entities with two autonomous intrinsic values.

According to the analysis of the way money is issued and associated to real production, it is no longer possible to claim that the supply of money is exogenously determined. Banks act on behalf of the economy and as long as they comply with the rules of double entry bookkeeping their emissions are determined by the need to monetise and convey (repeated transfers included) real output. However, if money becomes the form of real output as soon as it is issued, how can inflation still be possible? Is it not true that if Central Banks were to finance public deficits by printing money, inflationary gaps would result from these exogenous increases in the money supply? The apparent contradiction between the endogenous determination of money and the possible exogenous increase in the quantity of money can be dealt with by observing that inflation is an anomaly which can be due precisely to the fact that, in certain circumstances, the logic of bank money requiring money to be always endogenously determined is not complied with. Yet, another difficulty arises now. If it is plausible to blame the monetary authorities of underdeveloped countries for a great part of the inflationary increase in their domestic money supplies, the same interpretation can hardly be maintained against the Central Banks of industrialised countries. Compliance with the rules of modern banking does not allow for free monetary creation, and there can be little doubt that the most advanced banking systems work according to these rules. Where does inflation come from then? If only a small fraction of price increases can be attributed to the behaviour of monetary authorities, how can inflation reach the levels we have been accustomed to despite the fact that money is endogenously determined?

Table 1.1

Secondary bank | |||

liabilities | assets | ||

Workers | x | Firm F (Current output) | x |

The interrelationship between monetary and real variables allows ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of contributors

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I Inflation and unemployment: a monetary and structural framework for analysis

- Part II Inflation and deflation as monetary pathologies

- Part III Learning from the past

- References

- Author index

- Subject index