1

Introduction

Hans Mouritzen and Anders Wivel

The power structure in post-Cold War Europe has been unipolar, the one and only pole being a symbiosis between the United States and major EU powers. This symbiosis has affected the external and domestic policies of practically all states in Europe, be they members of the EU or NATO or not. Stability and democracy have been projected. The symbiosis has constrained, not least, the region’s non-pole powers. These are sometimes referred to as, for instance, the ‘small and medium powers’ which, as will be shown, is an analytically unfortunate label.

European pole powers (‘great powers’) with their power projection ability have a better chance of influencing the overall integration process. If necessary, they can credibly threaten not only to leave common undertakings, but thereby also to reduce or even destroy them, should that suit their interests. In contrast, non-pole powers are at the same time more dependent on strong international institutions and less able to influence their decision-making. For this reason the non-pole powers share problems that are somewhat different from those faced by the pole powers. In spite of this, however, it has been corroborated in a range of studies that non-pole powers respond differently to the seemingly shared problems. Specifically, they have responded heterogeneously to their geopolitical challenges in post-Cold War Europe. This leads to the puzzle that this book aims to solve: if non-pole powers experience the same problems in regard to Europe’s political order, as assumed by prevailing theories, why do they behave so heterogeneously?

The objective: explaining the external behaviour of non-pole powers in contemporary Europe

The objective of this study is to explain how the geopolitics of Euro-Atlantic integration affects the external behaviour of non-pole powers. Non-pole powers constitute a vast majority of European states and the number is growing. For instance, the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia following the end of the Cold War added 11 new non-pole powers. Moreover, the possibility of further fragmentation, notably in the post-Soviet space, remains high (Fawn and Mayall 1996). Many of the new states have joined the European ‘good company’ through EU and NATO enlargements. By 2005, 22 out of the EU-25 should be counted as non-pole powers. The countries next in line, Romania, Bulgaria, Croatia, FYR Macedonia and Turkey, all qualify as ‘non-pole’ in the EU context, although Romania and even more Turkey are pole powers in other relations. The same general pattern is discernible in NATO. The proportion of non-pole EU/NATO members has been growing significantly.

Although there has been an increase in literature on ‘small’ states in general and ‘small’ EU members in particular, there is no concise publication addressing the impact of the European power structure on the behaviour of the vast majority of European states.1 This volume seeks to fill that void. To be more specific, we do not aim to explain the Euro-Atlantic or European integration process as such, but instead how this process in turn affects the external behaviour of the non-pole states. The external behaviour of states includes here policies towards the EU—integration policy—as well as traditional foreign policies and their interaction. For reasons of manageability, we exclude the internal behaviour of states, although this is often an inherent part of their adaptation towards the power pole. This would belong to adaptation studies, proper (e.g. Mouritzen et al. 1996; Petersen 1998).

Generally, realists have faced serious problems when trying to understand contemporary Europe in general and the EU in particular (see Wivel 2004). We believe, however, that we have found a way to make sense of the EU/NATO as a power pole and, hence, to study contemporary Euro-Atlantic integration and its effects on foreign policies from realist premises. Our power and states-as-actors focus make this volume a realist one. This goes hand in hand with our principle of theoretical parsimony, the ambition to ‘explain much by little’.

In contrast to most modern realists, we re-introduce the notion of geopolitics, i.e. ‘the influence of geography on the political character of states, their history, institutions, and especially relations with other states’ (Hay 2003).2 Distance or spatiality being the fundamental category of geography, geopolitics should help us understand what distance between states (some of them being ‘pole powers’) means for their behaviour and the relations between them. Moreover, as noted in Hay’s definition, there is both a past and a contemporary aspect of geopolitics as well as a domestic one. One reason for our emphasis on geopolitics is the re-territorialization of international politics in the post- Cold War era.

In this way our theory, the constellation theory, breaks with neorealism. However, it fits nicely into the broader realist tradition. In particular, our theory may be seen as an addition to so-called neoclassical realism. Although sharing the flaws of much American realism, the virtue of neoclassical realism lies in its integration of foreign policy theorizing with IR as a whole. Also, we applaud the limited but systematic role it ascribes to the domestic sources of foreign policy.

This book makes three contributions to neoclassical realism. First, we expand it considerably by theorizing also on the non-pole powers, rather than solely the great powers.3 Second, we specify the effect of state location on foreign policy, thereby emphasizing the role of geopolitics (having received little attention in the neoclassical literature). Finally, we reformulate the concept of polarity in order to explain non-pole power behaviour.

What is a pole? What is a non-pole state?

‘Pole’, ‘great power’ and ‘small state’ are all contested concepts in the study of international relations. No consensus exists as to their definition, and even those who share a definition may find it difficult to agree on the identification of specific instances. Usually the concepts are defined in terms of the possession of power, i.e. resources ‘owned’ by the unit in question. Understood in this way, we are dealing with a continuous size variable. Delimitations regarding this variable may be made, in turn, according to absolute or relative criteria. In absolute terms, the dividing line between small states and great powers may be set at a population size of 20 million people, or a GDP of 400 billion euros. One may also construct elaborate indexes weighing together size of population, territory, GDP, defence expenditure and political competence/stability (see Joffe 1998; Pastor 1999; Waltz 1979; Wohlforth 1999). Whatever unit of measurement is used, a cut-off point is chosen on the scale. In relative terms, the cut-off point between great and small powers may be set at the top-10 in the world, or the top-5 in Europe, according to one of the above measurements. However, both absolute and relative criteria are arbitrary. There is no reason why precisely 20 million people should make a difference to the exercise of state power or why no. 5 in Europe should be characterized as a great power and no. 6 should not.

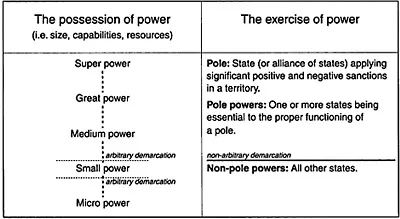

We suggest an alternative approach (Figure 1.1). Rather than delimiting pole from non-pole states on the basis of the power they possess, we focus on the power they exercise (Goldmann 1979). ‘Poles’ and ‘non-pole states’, we argue, must be defined and analysed in a specific spatio-temporal context. Characterization as a pole or a non-pole state reflects the state’s position in this context—not attributes possessed by the unit (Mouritzen 1991, 1998a). This relational perspective means that a state may be weak in one relation, but simultaneously powerful in another. For instance, Turkey may be a non-pole state in Europe, but a pole power in relation to some of the Caucasian republics. Thus, pole and non-pole states are defined in relational terms rather than in absolute or relative terms.

In contrast to systemic power structure, where the poles are delimited on the basis of relative capabilities, we operate with relational polarity, i.e. states (or alliances of states) with significant positive and negative sanctions in a certain territory. A hegemonic pole, a unipole, has even paramount positive and negative sanctions in this territory. In a grey zone, by contrast, there are two or more poles competing for power and influence. Power is exercised in relationships between one or more poles and the state, whose behaviour we wish to explain. A pole may carry a heavier ‘weight’ in one state than in the calculations of its very neighbour. For instance, during their first independence decade, the Euro-Atlantic unipole was stronger in Slovenia than in neighbouring Croatia, although both are ‘small’ splinter states from the former Yugoslavia. Relational polarity is our main explanatory device in this book.

Figure 1.1 Power criteria for classifying states.

A pole, in turn, may consist of one or more closely cooperating ‘pole powers’ (‘pole states’). In order to qualify as such, they should be essential to the pole’s power projection and proper functioning in its sphere. ‘Non-pole powers’ (‘non-pole states’) are all other states. Should they choose to revise their place in the structure, the structure can still persist with unchanged contours. They are stuck with the Euro-Atlantic power configuration and its institutional expression, no matter what their specific relation to it is.

The puzzle: the non-pole states’ heterogeneity of strategy

As being consistently the weaker parties in relation to one or more power poles, one would expect all non-pole powers to be strongly committed towards the establishment and consolidation of multilateral diplomacy, be it globally or regionally. Since the EU is the strongest and most realistic candidate ever in this direction, this commitment should be the clearest and most unambiguous in this case. However, European non-pole states have reacted in a variety of ways to the process of European integration. This heterogeneity is also reflected in the general foreign policy postures of the states. The Benelux countries were founding members of the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and the European Economic Community in 1957. As early as 1948, Belgium’s Prime Minister at the time, Paul Henrik Spaak, became the first President of the OEEC. In opposition to most European governments at the time he promoted an expansion of the competencies of the organization and even the first steps towards a supranational Europe (Dosenrode 1993:182). By contrast, the Nordic states—often characterized as ‘reluctant Europeans’ or ‘the other European Community’—explored alternative solutions to membership of the European integration project. They did not give up their attempt to create a Nordic customs union until 1970 and the first Nordic country, Denmark, joined the European Community as late as 1973. Finland and Sweden only joined in 1995 and even today Norway and Iceland remain outside the EU. Moreover, the behaviour of the Nordic states has varied once inside the EU. Denmark and to an increasing degree Sweden have been reluctant towards further institutionalization, whereas Finland has participated eagerly and even promoted a more active role for the EU in relation to North-West Russia.

Greece—much like Denmark and more recently Sweden—has preferred membership, but at the same time tried to limit its negative consequences for national autonomy. Until the turn of the century, at least, it has taken a different stance than the rest of the EU on matters concerning Turkey and Macedonia. Generally, Greece has been the ‘black sheep in the family’. Switzerland has remained outside the EU altogether despite the important potential for economic gains through membership (see Gstöhl 2002) and has, in contrast to other non-pole states in the region, pursued a foreign policy strategy emphasizing non-membership of international organizations. These observations are concurrent with numerous findings regarding the heterogeneous behaviour of ‘small states’. This indicates a puzzling freedom of manoeuvre for these states, when in fact they ‘should’ be uniformly supportive of European integration.

The puzzle remains in prevailing theories

Theories of European integration and international relations have a hard time explaining this heterogeneity. From economic theory we would expect small and highly industrialized states to be in favour of international institutions such as the EU (Gstöhl 2002:3–4; Mattli 1999:31–40). This is because regional integration allows small states to obtain benefits that are usually available only to large countries, i.e. economies of scale, increased competition and the opportunity to specialize. Furthermore, the benefits of integration are increased if the regional integration project is a major trading partner of the state, because membership allows the state to voice concerns over existing policy and influence new initiatives. This allows us to explain why some states are eager Europeans, but not why others are sceptical member states or reject membership altogether. Besides, it tells us nothing about the general foreign policy postures of small European states, except that they are expected to promote international economic integration.

Integration theory—‘the theoretical wing of the EU studies movement’ (Rosamond 2000:1)—has problems explaining the behaviour of non-pole states as well. From neo-functionalism we would expect European integration to benefit from a process of ‘geographical spillover’. In this process more and more countries join the integration project as a consequence of the efforts of elites being adversely affected from their outsider status (Haas 1958). The thesis was extrapolated from the early smooth history of European integration. It does account for the geographical enlargement of the EC/EU, but hardly for countries refusing membership or those striving for membership and then once inside spending most of their efforts safeguarding their autonomy—sometimes promoting different foreign policies than those favoured by the Union.

Liberal inter governmentalism, another prominent integration approach, focuses on the importance of the economic interest groups of the pole powers for the development of the integration project. The course of European integration is determined largely by the ‘grand bargains’ reached by the pole powers at intergovernmental conferences (Moravcsik 1998). Non-pole states, on the other hand, have little influence over the results. Their lack of relative power, most importantly their low levels of self-sufficiency and export-dependent economies, means that they are more severely affected by interdependence than the pole powers and therefore need policy coordination more badly. This intense preference for regional integration combined with only marginal influence on the pole powers means that they cannot credibly threaten to ‘go-it-alone’ or refrain from signing an agreement. At best, non-pole states may find themselves in a position to influence the distribution of side payments in return for support for a coalition of pole powers’ grand bargain. This may help explain why beneficiaries of the cohesion fund such as Ireland and Portugal have generally been more enthusiastic about integration than for instance the Nordic countries. However, it does not explain why a long-term net contributor such as the Netherlands is a constructive EU core country, whereas long-term net receivers such as Greece and Denmark are sceptics.

Adherents of the multi-level governance approach find that the member states are losing power due to collective decision-making and supra-national institutions: decision-making competencies are shared by different levels, and domestic actors act in national as well as supranational arenas (Hooghe and Marks 2001). On the one hand, this erosion of state power may be good news for the weaker member states, because it reduces the importance of state power. On the other hand, the limited resources of non-pole states may leave them worse off, because pole powers may still dominate decision-making, but now without having to pay side-benefits to them. In essence, the multi-level governance approach is indeterminate and leaves us with little guidance on how non-pole states may react to regional integration and how it might affect their foreign policies.

Theories of international politics do not fare any better when applied to the effect of regional integration on non-pole state...