Although there is a growing body of research exploring the transition to a more service-based orientation in complex product markets, the majority of this literature adopts what might be classified as a ‘manufacturer-active’ point of view; that is it explores the challenges faced by firms (e.g. aircraft & capital equipment manufacturers, building firms, etc.) seeking to ‘sell’ their re-conceptualized streams of revenue. There has been much less research exploring the challenges associated with the transition from traditional asset acquisition processes to ‘buying’ or procuring complex performance (PCP)—here defined as a combination of transactional and infrastructural complexity. This chapter explores the macro- and micro-economic context to this specific problem space and develops a preliminary conceptualisation of the process of PCP. It draws on two principle literatures: one focused on the boundary conditions firms consider when choosing to ‘make or buy’ a range of different activities from the market (e.g. Fine and Whitney, 1999; Gilley and Rasheed, 2000; Williamson, 1985; Grover and Malhotra, 2003) and the other on public procurement (e.g. Thai and Piga, 2006; Knight et al., 2007) and Public–Private Partnerships in particular (Broadbent and Laughlin, 2005; Froud, 2003). Three distinct governance challenges are presented: (1) contractual, (2) relational, and (3) integration. The chapter explores the implications of the conceptual model by developing a range of research propositions that are intended to be the foundations for future research.

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Buying the performance outcomes of a resource-in-use, rather than acquiring the resource and using it, is not a novel phenomenon: from the laundry where a customer purchases ‘cleaned clothes’ to the vehicle-leasing firm where a client contracts for ‘miles travelled’. Today, however, this approach is being increasingly applied to the procurement of complex performance: DuPont for instance, after years of outsourcing non-core services, awarded a long-term contract to Convergys to redesign and deliver the various human resource management (HRM) programs for its 60,000 employees in 70 countries (Engardio et al., 2006). Likewise, in the computing and telecommunications sectors for example, the volume of outsourced research & development (R&D) and manufacturing services is forecast to grow to almost $350 billion by 2009 (Carbone, 2005). Similarly firms like Infosys are developing and maintaining a range of mission critical information technology (IT) applications for numerous international financial institutions. The same trend is evident in public procurement: the UK government for example has long commissioned specific research projects from universities and private-sector institutions, but in recent years more and more complex research performance is being outsourced and contracted for: for instance, Serco has managed the national standards laboratory, a large-scale, internationally respected centre of excellence in measurement and materials science R&D, since 1995.

Interestingly, although there is a growing body of research exploring different aspects of this transition to a more complex service-based orientation (Potts, 1988; Armistead and Clark, 1992; Mathe and Shapiro, 1993; Miller et al., 1995; Hobday, 1998; Gadiesh and Gilbert, 1998; Wise and Baumgartner, 1999; Kumaraswamy and Zhang, 2001; Mathieu 2001a, 2001b; Brady et al., 2005; Davies et al., 2007), the majority of this literature adopts a ‘provider-active’ point of view; that is it explores the challenges faced by firms (e.g. aircraft and capital equipment manufacturers, building firms, etc.) seeking to ‘sell’ their re-conceptualized streams of revenue. There has been much less research on the challenges associated with the transition from traditional asset acquisition processes to ‘buying’ complex performance (e.g. Lindberg and Nordin, 2008; van der Valk, 2008). This represents a significant empirical and theoretical research opportunity because it is a global phenomenon that necessitates an understanding of the factors that influence both private- and public-sector organisational scale and scope. This exploratory chapter comprises two main sections. The first introduces the content of, and context to, the research—offering a model of performance complexity. In the second, the additive process of PCP problem space is presented as a series of three governance challenges: contractual, relational, and integration. The implications of the conceptualization are discussed in a range of propositions that can be viewed as foundations for subsequent research in this increasingly significant area of public- and private-sector procurement.

1.2 THE CONTENT AND CONTEXT OF PCP

Consider the provision of aero-engine ‘power by the hour’. Although inter- and intra-organisational boundaries have clearly been changed, the intrinsic complexities of aero-engine supply and support have not been removed by this procurement arrangement: these sophisticated capital assets still need to be paid for (depreciated) and supported, often globally, by a Maintenance-Repair-Overhaul (MRO) organisation, with the support of a range of external contractors. Moreover, although an apparently simple procurement arrangement, with airlines specifying x hours of flying time, closer consideration reveals a whole range of likely buyer conditions (e.g. short versus long haul, timing and location of maintenance operations) and provider caveats (e.g. provider contract assumes the engine doesn’t exceed certain operating parameters, etc.) in any contract. In sum, this is a good example of what the chapter means by complex performance outcomes and the additive challenge of PCP. ‘Power by the hour’ as an outcome actually means on-wing aero-engines operating within efficient and effective boundaries—this is complex performance. Buying this kind of outcome means that airlines have to make significant judgements about reconfigured sets of specialized and complex input capabilities—this is PCP.

This archetype provides a useful point of departure for this conversation, but in order to build a conceptually robust picture of PCP it is necessary to bound the distinct phenomenon before moving on to explore why and how organisations embark on the PCP process.

What is PCP?

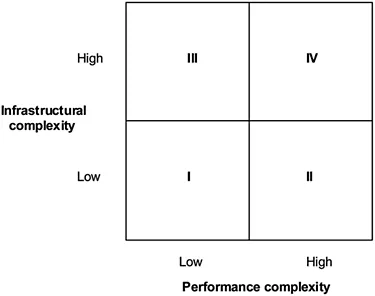

Noting that any complexity construct is relative, subjective, and a function of the level of analysis applied, the relevant literature highlights two dimensions of performance complexity that have particular relevance to subsequent procurement decisions.

The first relates to the performance complexity itself (Danaher and Mattsson, 1998), a function of characteristics such as the level of knowledge embedded in the performance (e.g. the ability to type up doctors notes compared with the ability to read an X-ray chart) and/or the level of customer interaction (e.g. scripted ‘performances’ compared with ‘performances’ that are “ … empathetic and facile with respect to language and culture”: Youngdahl and Ramaswamy, 2007). Knowledge-intensive and highly interactive services like management consultancy have traditionally presented a significant challenge for procurement processes because they are difficult to specify ex-ante and, correspondingly, difficult to measure and monitor. Unsurprisingly, this has often meant that they are a controversial area of public and private expenditure. Second, there is the complexity of the infrastructure through which performance is enacted. This complexity can be largely characterized by the extent to which it is “bespoke or highly customized” (Brady et al., 2005). Infrastructure procurement is often irregular, and, as a result, buyers often rely heavily on specialist suppliers, indeed increasingly firms “know less than they buy” especially in the light of recent outsourcing trends (Davies, 2003). Figure 1.1 combines these dimensions into a matrix of total procurement complexity.

The top-right quadrant of the matrix, labeled Category IV, represents the highest level of aggregate complexity and provides the preliminary definition of PCP:

Although further work will be needed to operationalise the two framing dimensions (and thereby generate empirical tests for the typology and its boundaries) in this preliminary work it is possible to further detail the other categories in order to reinforce the differential characteristics of Category IV. Table 1.1 below summarizes each category and provides illustrative examples.

Additionally, it would be interesting to explore how these types of complexity interact and modify over time. For instance, international engineering firms like Arup and Atkins use off-shoring strategies to manage knowledge and information (transactional complexity) through the life cycles of their own complex infrastructure provision, suggesting that simplification and complexity segmentation strategies will form an important part of any PCP arrangement. Equally, competitive, technological, regulatory, and legislative forces will inevitably alter relative positioning. The

Table 1.1 Categories of Performance Complexity

type III call centre example for instance could become a type I as infrastructure further standardizes and greater automation of analysis reduces the performance complexity.

Why Buy Complex Performance?

Although the strategic logic for the ‘make or buy’ (supply or buy) decision is normally efficiency maximization, a range of factors, such as global trade liberalisation, narrower definitions of core competencies, and greater technological complexity (Oliva and Kallenberg, 2003), seem to be changing the scale and scope of outsourcing. Customers of firms like Flextronics (electronics sector) and Li and Fung (garment sector) for example are no longer buying sub-contract manufacturing capacity but rather procuring ‘solutions’ to complex business problems. Although this suggests that buyers are seeking a broader range of strategic contributions from their suppliers, this appears to challenge the dominant theoretical, Transaction Cost Economics (TCE), logic for outsourcing. Assuming opportunism and bounded rationality (Rindfleisch and Heide, 1997) TCE asserts that firms attempt to minimize transaction costs by “assigning transactions (which differ in their attributes) to governance structures (the adaptive capacities and associated costs of which differ) in a discriminating way” (Williamson, 1985, p. 18). As a result, firms only internalize activities where adverse costs might arise from operational difficulties in a market exchange, primarily uncertainty, frequency, and asset-specificity1. However where there are high levels of asset-specificity, TCE suggests that hierarchy becomes the least-cost governance solution2. In other words, this logic suggests that organizations would/should not procure complex performance or that a purely transaction-based logic is insufficient to understand the PCP phenomenon. In a related discussion3 Holcomb and Hitt (2007) balance economizing arguments with a logic where “the complementarity of capabilities, strategic relatedness, relational capability-building mechanisms, and cooperative experience [are equally] important conditions. … for strategic outsourcing”. Using this balanced definition it is proposed that:

Proposition 1

PCP arrangements are considered where ...