- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Politics of Central Banks

About this book

This book is a study of power. In particular, it is a study of governmental power in Britain and France. Its focus is the changing relationship between the government and the central bank in the two countries, and it examines the politics of this relationship since the time when the Bank of England and the Bank of France were first created.

The book begins by considering the issue of governmental control generally. It then focuses on monetary policy making, and asks what has been the role of governments in this area and what freedom have central banks enjoyed? After a detailed historical analysis of this issue in Britain and France, the authors conclude by considering the likely role of the European Central Bank.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Central Banks by Robert Elgie,Helen Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 The politics of core executive control

The core executive may be defined as ‘all those organizations and structures which primarily serve to pull together and integrate central government policies, or act as final arbiters within the executive of conflicts between different elements of the government machine’ (Dunleavy and Rhodes 1990:4). The core executive corresponds to ‘the heart of the machine’, and consists of a ‘complex web of institutions, networks and practices’ (Rhodes 1995:12) which incorporates all the significant policy-making and coordinating actors in the executive branch of government, heads of state, heads of government, ministers and senior civil servants as well as central coordinating agencies, secretariats, committees and services. The term ‘core executive’ is one which has no normative connotations and which permits comparative analysis. It is the term which will be used in this book to examine both the politics of core executive control in general, and the politics of monetary policy in particular.

This chapter consists of two main parts. The first part examines the study of core executive control. In so doing, it sets the scene for Chapter 2, which explores the particularities of core executive/central bank control. The second part considers the changing patterns of core executive control over the last three centuries. In this way, it provides the background for Chapters 3 – 6 inclusive, which place core executive/central bank relations in Britain and France in an historical perspective. Overall, this chapter serves as an introduction to the politics of monetary policy and to the problem of core executive control in this area.

The study of core executive control

There are two sets of relationships that feature in the study of core executive control. The first set concerns those that occur within the core executive. This set reflects the relationships between the various actors within the core executive and the resources and constraints that they possess. For example, is the relationship structured so that the prime minister controls the decision-making process and exercises a form of individual leadership, or alternatively, is it structured so that the prime minister is obliged to share power within the cabinet and exercise a form of collective leadership? In this set of relationships, the issue of core executive control is concerned with the internal politics of the core executive. By contrast, the second set of relationships concerns those which occur between the core executive and external forces. This set reflects the relationships between the core executive and the various actors in the wider political process, such as trade unions, business groups and political parties. For example, does the core executive have the capacity to shape the demands of the actors in the general environment within which it operates, or does it simply respond to the demands generated by those actors within that environment? In this set of relationships, the issue of core executive control is concerned with the external ‘reach’ of the core executive.

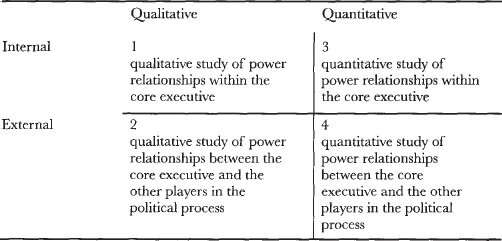

Just as there are two sets of relationships in the study of core executive control, so there are two main methodological approaches to the study of core executive control. The first is a qualitative approach. This involves a careful unpacking of the formal and informal powers of the different actors both inside and outside the core executive. It identifies the context within which the core executive operates and examines the attitudes and behaviour of individuals and groups who operate within that context. It is an essentially descriptive approach, and represents the traditional way of studying the issue of core executive control. The second is a quantitative approach (or at least a semi-quantitative approach). This only rarely involves the measurement of objectively identifiable criteria; instead, more often than not, it consists of calculations based on subjectively manufactured scales, tables and rankings derived from ordinal data. It provides a numerical indication of the respective powers of the players concerned. It is an essentially analytical approach, and is to be found in some of the more recent studies of core executive control.

The identification of two sets of relationships in the study of core executive control and two distinct approaches to the study of core executive control generates a matrix, which is shown in Table 1. This matrix provides an indication of the various different types of core executive studies that can and have been undertaken. Cell 1 corresponds to a qualitative study of power relationships within the core executive, whereas Cell 3 corresponds to a quantitative study of those same power relationships. Similarly, Cell 2 signifies a qualitative study of power relationships between the core executive and the other players in the political process, and Cell 4 signifies a quantitative study of the same. It is useful to identify and briefly examine examples of each of the four types of core executive studies so as to show the various issues involved in the politics of core executive control, and so as to set the scene for subsequent chapters in which both qualitative and quantitative methods are used.

The first type of core executive studies, corresponding to those in Cell 1, comprises qualitative studies of power relationships within the core executive. In the main, this type of core executive studies concerns in-depth accounts of internal core executive power relations in individual countries. In a British context, for example, this work is to be found in the long-running debate about the relative powers of the prime minister and cabinet. This debate produced two mutually exclusive schools of thought: the prime ministerial government school and the cabinet government school. On the one hand, Richard Crossman famously declared that the ‘post-war epoch has seen the final transformation of Cabinet Government into Prime Ministerial Government’ (Crossman 1972:51), whereas on the other hand, Patrick Gordon Walker argued that a ‘Prime Minister who habitually ignored the Cabinet, who behaved as if Prime Ministerial government were a reality—such a Prime Minister could rapidly come to grief (Walker 1970: 95). Supporters of both sides provided evidence to back up their argument based on their own experience of core executive operations and/or on interviews with others with such experience. In particular, Crossman emphasised the importance of the centralisation of political parties and the growth of a centralised bureaucracy (Crossman 1972:51–2), while Walker argued that ‘neither of [these points] is as novel nor as significant as is sometimes made out’ (Walker 1970:86).

If, for the most part, this type of core executive studies has focused on core executive power relations in individual countries, then there are still some qualitative studies which examine internal core executive power relations comparatively. Perhaps most notably, Anthony King has studied the relative influence of prime ministers ‘within their own systems of government’ (King 1994:151). By focusing on whether prime ministers head single-party or multi-party governments, the degree of control that prime ministers wield over the careers of other politicians within the government, the public visibility of prime ministers and the legacy of history, King establishes a ranking of prime ministers according to the degree of their influence within government (King 1994:151–61) (see Table 2). This table is based on secondary information rather than interviews with primary sources, but it still provides an interpretation of the comparative strength of these political leaders within their own systems of government which is derived from an essentially qualitative approach.

Table 1 Types of core executive studies

The advantage of this type of study is that it can provide a full description of the complexities of political life. As one writer notes about the merits of another similar type of study, it can ‘proffer a highly sophisticated account of the power relationships’ (Devine 1995:148) between actors within the core executive.

The second type of core executive studies, corresponding to those in Cell 2, comprises qualitative studies of power relationships between the core executive and the other actors in the political system. One such study, even though it calls upon certain figures to back up its points, has been conducted by Richard Rose (1985). This is a comparative study of selected Western governments and, in particular, of the power of the US president in comparison to European presidents and prime ministers. Rose begins by describing some of the resources that these political leaders can mobilise in the context of their own core executive. In this sense, he is engaging in the same type of study as King above. However, Rose then goes on to examine the ‘total amount of resources mobilized by government’ (Rose 1985:10).

Rose identifies three factors which serve to indicate the position of the government, or core executive, within the wider system. First, there is the proportion of gross domestic product claimed by government as tax revenue. Needless to say, some governments command a larger portion of their natural resources than others, and some governments collect more government revenue centrally than others. These indicators point to the comparative centralisation of the core executive and, therefore, to the extent of its reach. Second, there is the extent of centralisation of public employment. For Rose, public employment is a major resource of government because ‘insofar as a leader requires followers, then public employees are reliable followers, being bureaucrats paid by the state to follow rules laid down from above’ (Rose 1985:11). Again, some governments employ a larger number of employees than others and so the reach of certain core executives is greater than others in this respect. Third, there is the proportion of laws sponsored by governments annually. For Rose, this is another indication of the core executive’s ability to influence the political system. Once again, there are cross-national variations in the amount of government-sponsored legislation which is passed annually, and so there are also cross-national variations in the relative influence of core executives.

Table 2 King’s ranking of prime ministers according to their degree of influence within government

High | Medium | Low |

Germany UK Greece Ireland Portugal Spain | Austria Belgium Denmark Swedan | Italy Netherlands Norway |

Source: King (1994): 153

It scarcely needs to be said that there are certain problems with Rose’s analysis. For example, the assumption that core executive influence increases proportionally to the level of public employment is highly questionable. After all, the larger the bureaucracy the more unwieldy it may become and the more interests it may generate to which the chief executive is obliged to respond. Nevertheless, it remains that Rose’s article is a good example of a qualitative approach to the study of the position of the core executive in relation to the wider political system. In this respect, it benefits from the general advantages of this type of approach that were identified above.

The third type of core executive studies, corresponding to those in Cell 3, comprises quantitative studies of power relationships within the core executive. The most imaginative study in this category is by Patrick Dunleavy (1995), who measures the relative importance of the different actors within the British core executive under the prime ministership of John Major. He does so by examining the functioning and membership of cabinet committees and subcommittees. He assumes that committees are more important than subcommittees, that cabinet ministers are more important than non-cabinet ministers and that committee chairs are more important than committee members (Dunleavy 1995:306–7). He then proposes a formula which indicates the relative importance (or weighted score) of each committee and subcommittee. On the basis of this formula, he calculates the relative influence of each committee and subcommittee member by dividing the committee or subcommittee’s weighted score by the total number of members plus one for the position of the chair and then calculates the relative influence of the chair by doubling this figure.

Dunleavy’s formula for measuring the relative importance of the actors within the British core executive

The proposed formula is:

100*S* (C/N)

where:

S is the status of the committee with a committee counting as 1.0 and a subcommittee counting as 0.5;

C is the number of cabinet members who sit on the committee or subcommittee;

N is the total number of people who sit on the committee or subcommittee.

Source: Dunleavy, 1995, pp. 306–7.

When the calculations are made for all cabinet and non-cabinet members across all committees and subcommittees, the findings are both striking and yet intuitively correct. The prime minister scores far higher (256 points or 14.9 per cent of the total share) than any other cabinet member, reflecting his/her multiple positions of influence throughout the committee structure. There is then a first-ranked group of three ministers, the Foreign Secretary, the Secretary of State for Defence and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who score significantly higher (155, 138 and 110 points respectively) than other cabinet members and who are well placed to shape the decision-making process. There are then second, third and fourth-ranked groups of ministers corresponding to the scores that they achieve and the relative degree of influence that they possess. In the article, Dunleavy then goes on to discuss these findings. In particular, he examines the linkages that occur across committees and the appointments that the prime minister needs to make in order to ensure that politically ‘friendly’ ministers control the most central positions in the cabinet decision-making process.

As Dunleavy himself notes, there are good reasons to be ‘cautious in interpreting the numerical estimates’ (Dunleavy 1995:319). Indeed, he states that these scores ‘should not be fetished, nor should any fine or precise significance be attached to them’ (ibid.). They are, after all, simply calculations based on a number of limiting, subjective and contestable assumptions. However, this approach to the study of control within the core executive has its merits. Most notably, it provides the opportunity for systematic cross-temporal and comparative research. In this respect, though, as Dunleavy again notes, its value is still primarily heuristic in that it provides an indication of the sorts of research questions that need to be asked rather than an answer to those self-same questions.

The final type of core executive studies, corresponding to those in Cell 4, comprises quantitative studies of power relationships between the core executive and the other actors in the political system. One useful study in this respect has been suggested by Lane and Ersson (1991:264–7). They establish what they call the central government influence index. This gives a numerical indication of the degree to which citizens and collectivities are able to influence political decision-making within the polity. In so doing, it provides a way of measuring the general reach of the core executive comparatively.

Lane and Ersson’s index is derived from an examination of three influence mechanisms. Each mechanism is classified ordinally and then the scores for each country are simply totalled. The higher the total, the greater the extent to which citizens are able to influence policy making and so, arguably, the smaller the reach of the core executive. First, Lane and Ersson examine the capacity of citizens to influence policy makers by way of the frequency of referendums and the degree of proportionality in electoral formulae. So, for example, Switzerland scores 4/4 in this category because there is frequent recourse to referendums and because there is a proportional electoral system. Second, they consider the capacity of elites to influence policy making by way of the propensity towards both consociationalism and corporatism. Here, for example, the Netherlands and Norway both score 2/2 because they have highly developed consociational and/or corporatist procedures. Finally, they assess the importance of citizen influence by way of the presence of minimum-winning cabinets which are ‘conducive to effective translation of citizen preferences into policies’ (Lane and Ersson 1991:265). According to this category, the UK scores 4/4 and Italy scores 0/4. By summing the various scores, citizens appear most able to influence policy in Norway (7/10) and least able to do so in Greece, Portugal and Spain (3/10). It might be argued, then, that the core executive reaches least far in Norway and furthest in this latter set of countries.

The same caution is needed when interpreting these results as was needed when interpreting the results produced by Dunleavy above. Indeed, perhaps a greater degree of caution is needed in the case of the central government influence index because of its extremely broad range and the rather simplistic method of classification. At the same time, though, this index has the same general advantages as the methodology identified by Dunleavy in that it permits comparisons both across time and across countries, and that it highlights certain features of the politics of core executive control which may then be explored more fully.

This book adopts both a qualitative and a semi-quantitative approach to the study of core executive/central bank relations in Britain and France. It describes both the historical and the contemporary relationship between the two institutions in the two countries and uses primary and secondary material in order to do so. It also establishes a means by which the degree of core executive control over the central bank can be measured and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The politics of core executive control

- 2 Core executive/central bank relations

- 3 The core executive and the Bank of England (1694–1987): from autonomy to dependence

- 4 The core executive and the Bank of England (1988–97): the primacy of domestic politics

- 5 The core executive and the Bank of France (1800–1981): the old regime

- 6 The core executive and the Bank of France (1981–97): shadowing the Bundesbank

- 7 The political control of economic life

- Appendix 1 Calculating Central Bank independence

- Appendix 2 Bank of England independence, 1694–1997

- Appendix 3 Bank of France independence, 1800–1997

- Appendix 4 European Central Bank independence

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index