eBook - ePub

Organizing Industrial Activities Across Firm Boundaries

Anna Dubois

This is a test

Share book

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organizing Industrial Activities Across Firm Boundaries

Anna Dubois

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The way in which industrial activities are organised among firms is a fundamental theoretical concern. In practice, firms have found these matters, referred to as make-or-buy issues, difficult to analyse. Organising Industrial Activities Across Firm Boundaries succeeds in combining an analysis of the theoretical background to such issues with an in-depth case study of the practical consequences and implications. The book is an important contribution to the literature on networks, business relationships, out-sourcing and the division of labour.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Organizing Industrial Activities Across Firm Boundaries an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Organizing Industrial Activities Across Firm Boundaries by Anna Dubois in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

Introduction

During the development of a new truck model, SweFork—a manufacturer of electrical trucks for materials handling—had to decide what parts of the new truck should be produced in-house and what parts should be bought from suppliers. Numerous aspects had to be considered and during the development process additional aspects arose which made the situation complex and difficult to overview. In addition, when the production of the new truck begun, various changes in design and production had to be effected, which altered the conditions for the decisions regarding whether to make or to buy the parts. Some of the considerations regarded as important for the make-or-buy decisions were related to SweFork’s internal operations, while others were related to what the suppliers could do for them. One important internal aspect was that SweFork’s own production capacity, used to produce several truck models, was under pressure, which favoured buying of the parts. Later, a decrease in demand for the trucks changed this situation, which became characterised by excess capacity. Moreover, numerous design changes, considered teething troubles, were needed during the first years of production, making it more difficult to buy than to make certain parts. This was a result of the fact that once a particular component had to be redesigned this often called for changes of related components which, in turn, entailed changes of components connected to them, and so forth. Consequently, these matters were complex to handle. This made it difficult to involve the various suppliers in the complicated problem solving process. As a result, the suppliers were often asked for quotations when the design of the components was already completed. Based on SweFork’s drawings they then had to consider whether the components fitted into their current production operations and what adjustments were needed to cope with SweFork’s requirements. For the suppliers, these considerations depended on how the operations needed to produce SweFork’s components fitted those already undertaken by them for other customers. Hence, the suppliers’ current production operations entailed both restraints and possibilities of various kinds. Some suppliers would have preferred to be involved in the design of the components since this would have made it possible for them to better relate the production activities for the new truck model with then: existing ones.

The main question for SweFork may be seen as a practical one. Under what conditions would it be advantageous to let suppliers take on the production of individual parts of the truck? SweFork spent a great deal of time and effort in solving the make-or-buy problems. This resulted in certain cases in out-sourcing some part of the production, and in some cases in maintaining in-house production. However, no obvious solutions could be found as every make-or-buy situation was found to be closely connected with various other aspects. How to organise the activities within the firm turned out to be related to how these were connected with the suppliers’ activities, and this is, in turn, was associated with how the suppliers related their activities to their suppliers and other customers, and so on. Thus, a more relevant articulation of the original question turned out to be how could the complex interrelations among all the parts and the activities needed to produce them be handled?

This book is an attempt to analyse situations of this kind. The issue is obviously important for firms handling make-or-buy situations in real life for their own good, as reflected in the example above. As early as in the 1940s Culliton pointed to the need for practical guidance in these matters and the need appears to remain.

The most that is done is to list the possible advantages and disadvantages of making and of buying, without attempting to set up a satisfactory procedure for discovering whether, in a specific instance, making or buying could be expected to bring the greater advantages.

(Culliton 1942:1)

Although this may seem to be a rather practical problem, the issue is, and always has been, fundamental to the understanding of economic efficiency in industrial systems. Economists addressing the division of labour have attempted to design models explaining firm and industrial performance. However, to be able to generalise and aggregate the analysis they have simplified the context in which these problems are dealt with. Most often these simplifications encompass assumptions about independent firms and markets on which the firms exchange their products. These ‘pure’ forms of activity co-ordination, i.e., either through internal co-ordination (firm) of interdependent activities, or through market exchange of independent activities, seem, however, to be the exceptions rather than the rule in the real world. Interdependence of different kinds blurs the firm boundaries and thus makes individual make-or-buy situations difficult to delimit. The problems experienced by SweFork described above reflect some of the difficulties in every attempt to draw boundaries around firms and the things they do.

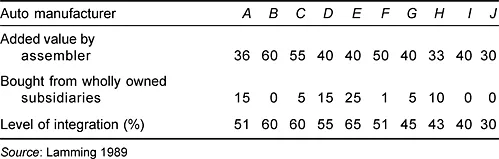

Table 1.1 Integration levels in the European automotive industry

|

Dealing with interdependence among activities in industrial systems, this book provides a framework for analysis of the make-or-buy problems experienced by firms, as well as the theoretical issue of the industrial division of labour.

In the remainder of this chapter a further presentation of the practical and theoretical background to the problem is presented. Chapter 2 provides a framework for analysis of the efficiency of activity structures in industrial systems. Chapter 3 provides empirical illustrations of the complexity characterising activity structures and how the interdependence among activities causes problems when changes are effectuated. In Chapter 4 the activity interdependence is further analysed and in Chapter 5 certain boundaries resulting from the interdependence are identified. Lastly, in Chapter 6 some questions related to the dynamics of industrial systems are raised.

PRACTICAL BACKGROUND

Empirical studies have shown that the degree of vertical integration differs extensively among firms even in one and the same industry. Lamming’s (1989) study, carried out within the European automotive industry, identified degrees of vertical integration varying between 30 and 65 per cent (see Table 1.1).

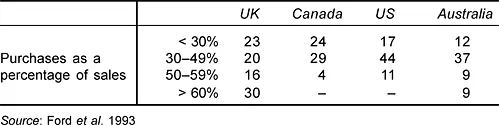

The large variation in the degree of vertical integration even within industries is interesting, as it implies that there are no given rules or answers as to how much should be made in-house and how much should be bought from suppliers. In addition, differences in terms of the degree of vertical integration among firms in different countries have also been found (Ford et al. 1993; see Table 1.2).

A study of 123 Swedish firms showed that 70 per cent of them purchased more than 40 per cent of then turnover and, for almost every fifth firm, that the purchase share extended 70 per cent (Håkansson 1989). Thus, large variations in vertical integration in industries as well as between countries have been identified. There are no clear reasons for this variation.

Table 1.2 Purchases as a percentage of sales in four countries

|

However, there is evidence of decreasing degrees of vertical integration in general. According to Ford et al. (1993:208): ‘There appears to be some consensus that there is an increasing move towards “buy” rather than “make” and that this is a good idea’.

Their empirical survey, including UK, US, Canadian and Australian firms, supported this tendency of firms moving towards increasing their purchase rate, although some firms moved in the opposite direction. The tendency towards decreasing degrees of vertical integration has also been identified by others (Dirrheimer and Hubner 1983; Barreyre 1988; Lamming 1993). According to Barreyre out-sourcing, or ‘impartition’ as he calls it, is not a new phenomenon since, for instance, subcontracting was common centuries ago in areas such as shipbuilding and textile industries (Barreyre 1988:509). However, historically the general behaviour was to make rather than to buy:

Sixty years ago large manufacturing companies in Europe as well as in the USA had a strong propensity to vertical integration. For several reasons the fully integrated factory of Henry Ford was a model for many firms. Managers were often reluctant to sub-contract, for instance; they tended to minimise external dependency, freight or taxes in order to get a better added value/sales ratio. Although exceptions could be mentioned, this pattern of behaviour prevailed for years in the pre-marketing era and the heritage has not yet entirely disappeared. Consequently, until the end of the 1960s, nations primarily exchanged either raw materials or fully finished products; international production-sharing was little developed compared to what it is at present.

(Barreyre 1988:518)

Furthermore, Barreyre (1988:510) goes on to argue that both the importance and the frequency of out-sourcing decisions are increasing, which he explains in terms of six major attributes or changes in the environment:

1 Accelerating technological change and obsolescence, which require faster depreciation of capital and know-how investments.

2 Discontinuity, which accentuates the need for organisational flexibility in the short term and strategic mobility in the long run.

3 The difficulty of maintaining sufficient company profitability in a context of crisis.

4 The increasing complexity of many products and the variety of processes necessary to produce each part of the whole.

5 The growing number of laws, rules and regulations which impose social constraints on firms in advanced societies and which accentuate the rigidity of industrial systems.

6 The intense world-wide competition which is both a cause and a consequence of striving for increased productivity through large-scale production.

The first and fourth points, dealing with technological change resulting in increasing technological complexity of both products and production processes, have been especially emphasised by others (Hayes and Abernathy 1980; Ford et al. 1993; Gadde and Håkansson 1993). Ford et al. (1993:213) argue that ‘no company possesses all of the technologies that are the basis of the design, manufacture and marketing of their offerings’. For this reason, firms are dependent upon the skills of others: ‘Increasingly, the escalating costs of R&D, the rate of technological change, and the “intensity” of the technology in many products means that this dependence on others is growing’ (Ford et al. 1993:213).

Thus, the general tendency seems to be towards buying rather than making. However, regardless of the direction of make-or-buy decisions, they also seem to be problematic for the firms undertaking them for several reasons. In addition, they seem to be neglected as strategic issues (Culliton 1942; Jauch and Wilson 1972; Leenders and Nollet 1984; Ford et al. 1993). As early as in 1942 Culliton argued that firms often disregarded the presence and importance of these considerations: ‘It is not improbable…that some of the businessmen who said that they had no make or buy problems, more accurately could be said to have had the problems but failed to recognise them’ (Culliton 1942:2).

More recently, Ford et al. (1993) found evidence of the problem still existing arguing that: ‘…few companies takes a strategic view of which of their supposedly mainstream activities could or should be bought in and which should continue to be carried out in-house’ (Ford et al. 1993:211). For instance, they found that many companies seem to be much more willing to buy in mor...