eBook - ePub

The Economics of the Latecomers

Catching-Up, Technology Transfer and Institutions in Germany, Japan and South Korea

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Economics of the Latecomers

Catching-Up, Technology Transfer and Institutions in Germany, Japan and South Korea

About this book

This book examines the spectacularly successful economies of East Asia, Japan and South Korea. The comparison of the 'catching-up' process in Japan and South Korea includes studies of the iron and steel and semi-conductor industries. The author shows the difficulties involved in trying to detect general patterns of development, as both countries appear to respond to different technological imperatives. As a result general models of development should be treated with caution, given the need to consider different historical and institutional contexts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Economics of the Latecomers by Jang-Sup Shin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

ON METHODOLOGY

1

LATE INDUSTRIALISATION AND CATCHING - UP

‘Local convergence without global convergence’1 – this is the broad statistical picture of the catching-up record in the world economy since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. There emerges a clear trend of long-term convergence both in per capita income and labour productivity among the sixteen OECD countries, whereas it is never evident outside the OECD countries or on the global level. Moreover, the convergence among the OECD countries was ‘local’ in another sense: it was only pronounced during the period after the Second World War.

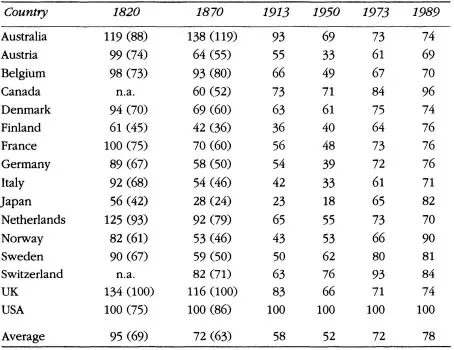

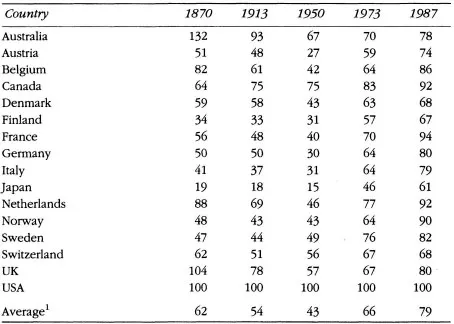

As Table 1.1 shows, the ratio of average per capita GDP (gross domestic product) of the follower countries to that of the leader country increased from 69 per cent in 1820 to 78 per cent in 1989. The same trend can be observed in labour productivity. The ratio of average labour productivity of the follower countries to that of the leader country increased from 62 per cent in 1870 to 79 per cent in 1987, as can be seen in Table 1.2. Regressions between initial levels of labour productivity (or per capita GDP) and their growth rates also show high inverse correlation, which implies that, the lower the initial levels of labour productivity (or per capita GDP), the higher their growth rates were.

This convergence process among the OECD countries has been far from monotonic. In fact, the phenomenon of divergence was stronger until 1950. The arithmetic average of comparative GDPs of the follower countries decreased from 95 per cent in 1820 to 52 per cent in 1950, if the USA is taken as the leader country. During the period 1820-1870, if the UK is taken as the leader country, which seems to fit the reality of the period better, the same figure also decreased from 69 per cent to 63 per cent (Table 1.1). In particular, the period of 1870-1950 was one of ‘forging ahead’ by the USA, then the clear leader country. In terms of both per capita GDP and labour productivity, the USA grew faster than the follower countries (Tables 1.1 and 1.2). It was only after the Second World War that the convergence force became strong enough to more than offset the previous divergence. The follower countries substantially narrowed the gap with the USA in terms of both per capita GDP and labour productivity during the post-war period (Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

Table 1.1 Convergence and divergence among the OECD countries: changes in comparative levels of per capita GDP (US per capita GDP = 100)

Source: calculated from Maddison (1991, table 1.1)

Notes: | 1 numbers in parentheses represent comparative per capita GDPs when that of UK is 100 2 average means the arithmetic average of fifteen countries excluding the base country |

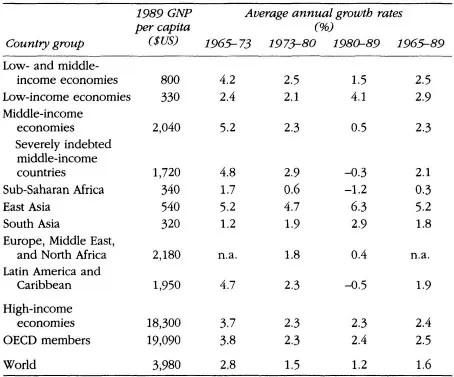

This convergence process, however, was not extended outside the OECD countries. Low- and middle- income countries, commonly called ‘developing countries’, in general did not catch-up with high-income countries. As Table 1.3 shows, the average annual growth rate of per capita GNP of low-and middle-income countries during 1965-1989 was 2.5 per cent, which was the same as that of the OECD countries. Consequently, the income gap between country groups did not shrink. In 1989, per capita GNP of low- and middle-income countries ($800) remained less than 5 per cent of the OECD countries’ ($19,090).

There is also regional and temporal disparity within developing countries. It may appear from Table 1.3. that low-income economies with an average growth rate of 2.9 per cent have been narrowing the gap with high-income economies. But this is mainly due to the unusually high growth rate of China, which contains around 38 per cent of the whole population of low-income countries.2 Its per capita income has grown at a rate of 5.7 per cent per annum during the period. If China is excluded, the average growth rate of other low-income countries is less than 1.8 per cent, far lower than that of the OECD countries.3 The poorest countries, mostly situated in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have been falling behind. Per capita GNP of these two regions grew at 0.3 per cent and 1.8 per cent respectively. The only region which has narrowed the income gap with high-income countries is East Asia. The average growth rate of per capita GNP in this region has been more than twice that of the OECD countries. Latin American and Caribbean countries seemed to have narrowed the income gap with the OECD countries before 1980, but they began rapidly falling behind afterwards.

Table 1.2 Convergence and divergence among high-income countries: changes in comparative levels of productivity (US GDP per man-hour = 100)

Source. Maddison (1991, table 3.4)

Note: 1 arithmetic average of fifteen countries excluding the USA

As far as the factual descriptions of ‘catching-up, forging ahead and falling behind’ above are concerned, there is little disagreement among historians or economists.4 The trouble is with its interpretation. Various attempts have been made to explain the implications of the picture described above. Yet, it does not seem that the methodological under-pinnings of those explanations have been fully grasped, resulting in some confusion in understanding the actual process of catching-up. In the following, we divide previous discussions into three main strands according to their different methodological approaches.

Table 1.3 Convergence and divergence among country groups during the post-Second World War period

Source: adapted from World Bank (1991, tables A.2 and table 1)

The first strand can be called the ‘aggregate approach’, which is more concerned with the overall catching-up across countries than that of individual countries. It starts from the statistical picture based on the average behaviour of country groups. Here, the main questions are whether convergence has occurred across countries or country groups and, if so, what are the central factors behind it. By nature, this approach is based on some universal concepts which are employed for the aggregation across countries. Abramovitz’s (1979; 1986) work, which has triggered the recent wave in the catching-up debate, would be the most elaborate version of this approach so far.

By contrast, the second and third strands deal with the catching-up process from the viewpoint of individual (or groups of) latecomers. The second is, however, different from the third in that it is more concerned with the external conditions of the latecomer. The studies of ‘technological entry barriers’, which have been tackled by some neo-Schumpeterian economists constitute this second strand. The third strand is in particular related to Gerschenkron’s works (1962; 1968; 1970). His approach differs from the second strand in that it is directed more at questions about the internal conditions of catching-up countries than at external conditions. And, in contrast to Abramovitz’s approach, Gerschenkron argues for an explanatory schema that accommodates different factors across countries, emphasising the limitations of universal propositions.

1.1 ABRAMOVITZ: A UNIVERSAL PROPOSITION

Abramovitz’s (1979; 1986) approach to catching-up starts from the so-called ‘catch-up hypothesis’, that is, the inverse relation between initial levels of economic development and its growth rates across countries, whether they are measured by labour productivity or per capita income. If this hypothesis is true, the more backward a country, the higher is its growth rate of productivity (per capita income), hence there emerges convergence across countries. But, as discussed above, the hypothesis holds only locally: it is conditioned by space and time. Some qualifications are therefore necessary if one wants to save the applicability of the hypothesis.

Abramovitz attempts one of the most comprehensive qualifications in this regard. The concepts of ‘potential’ and ‘realisation’ are central here. He regards the productivity (or technology) gap only as one component of the potential for catching-up, because it does not necessarily lead to economic progress in latecomers by itself.5 So comes his first qualified version of the catch-up hypothesis: ‘Being backward in level of productivity carries a potential for rapid advance.’6

Abramovitz adds another component to the potential, i.e., ‘social capability’. He identifies a country’s social capability as ‘technical competence, for which … years of education may be a rough proxy, and its political, commercial, industrial, and financial institutions which … [are] characterized in more qualitative ways.’7 If the technology gap is an external factor affecting the potential of latecomers, social capability is an internal factor affecting the potential of latecomers. The ‘total potential’ for catching-up is determined by the combination of the technology gap and social capability. Thus, Abramovitz proposes his second qualified version of the catch-up hypothesis as follows: ‘[A] country’s potential for rapid growth is strong not when it is backward without qualification, but rather when it is technologically backward but socially advanced.’8

The catch-up hypothesis is further qualified by the introduction of the concept of ‘realisation’. Abramovitz notes that most Western European countries reached a similar level of social capability to that of the leader country towards the beginning of the First World War. The second version of the catch-up hypothesis indicates that convergence should have occurred from that time. But it did not happen because of ‘the irregular effects of the Great War and of the years of disturbed political and financial conditions that followed, by the uneven impacts of the Great Depression itself and of the restrictions on international trade’.9 Rather, during the interim period of 1913–1950, a rapid growth potential in the follower countries was further accumulated as the USA forged ahead. Convergence became strong only after the Second World War, with the emergence of the international conditions favourable to catching-up.

Hence, Abramovitz’s third qualified version of the catch-up hypothesis: ‘The pace at which potential for catch-up is actually realised in a particular period depends on [realisation] factors limiting the diffusion of knowledge, the rate of structural change, the accumulation of capital, and the expansion of demand.’10 For Abramovitz, the match between the accumulated (total) potential before the end of the Second World War and the emergence of realisation factors in the post-war period explains ‘the Golden Age of Capitalism’.

From these qualified versions of the catch-up hypothesis,11 interpretations of the failure cases follow. As regards the reasons for the absence of convergence among the OECD countries during the nineteenth century, Abramovitz explicitly points to the divergence in social capability: ‘social competence for exploiting the then most advanced methods was still limited, particularly in the earlier years and in the more recent latecomers.’12 He does not explicitly discuss the applicability of his view to the current developing countries. But he implicitly suggests that the low level of social capability in these countries hindered them from exploiting the existing technology gap, although realisation factors were favourable during the post-war period.13

Other studies of the catch-up hypothesis stand on the same position. For instance, Baumol (1986) suggests that low levels of industrialisation and education in poorer less developed countries have barred them from utilising the technology gap. Dowrick and Gemmel (199D confirm Baumol’s suggestion by using a regression model.

A characteristic feature of Abramovitz’s analysis is the employment of the averaging method in detecting principal causes.14 To rely on the average is useful, especially when one deals with a large sample. But this method has its own limitations, one of which is the tendency that the interpretations attained from the cases which have a significant impact on the average are often applied to other cases which are not detected by the average. This practice assumes, implicitly or explicitly, a universal set of cause and effect across countries.

In Abramovitz’s analysis, what actually has a significant effect on the aggregate picture of his sample is the post-war catching-up process. During this period, it is plausible to regard the high level of social capability as a cause for catching-up common to all the OECD follower countries. But this interpretation relies crucially on the accidental situation that the level of social capability was separated from that of technology, that is, the situation that a large technology gap exists without a significant gap in social capability among the OECD follower countries.

A problem arises, therefore, if one tries to apply this interpretation to other periods or other countries. As we pointed out above, Abramovitz explains the absence of catching-up in the nineteenth century among the OECD countries by the disparities in social capability. But how meaningful is this interpretation? Does it make sense to say that the latecomers in the nineteenth century could not narrow the technology gap with their forerunners because they lacked sufficient social capability?

There were also local cases of technological catching-up which did not appear in the aggregate picture. Although data of per capita income or labour productivity do not show convergence among European countries in the nineteenth century (Tables 1.1 and 1.2), it is widely documented and accepted that some European countries, such as Germany, France and even Russia, rapidly narrowed their technology gap with Britain. Germany even overtook Britain in certain industries, including steel and chemicals. Likewise, the East Asian NICs have rapidly narrowed their technology gap with advanced countries in spite of the general failure of catching-up by the developing countries during the post-war period. What can be said about these local cases of catching-up? Is it plausible to say that they were successful in catching-up because they had already enlarged their social capability successfully before they began reducing the technology gap with their forerunners?

These are essentially questions of causa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Foreword by Professor Chris Freeman

- Preface

- INTRODUCTION

- Part I On methodology

- Part II On interpreting history

- CONCLUSIONS

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index