- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Unpaid Work and the Economy

About this book

In economics, the voluntary sector is surprisingly understudied. In order to fully understand economics, unpaid and voluntary work needs to be taken into account and afforded the same status as paid activities. This book constitutes a rigorous economic analysis with special emphasis on gender issues and covers every conceivable angle of unpaid work and all its ramifications for the modern economy.

The unified vision offered by this group of leading contributors ensures this book is a work of excellent quality. There is every chance it will become a seminal study on unpaid work and as such will provide a useful reference for students and academics involved in gender studies, econometrics, and consumption studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Unpaid Work and the Economy by Antonella Picchio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 A macroeconomic approach

to an extended standard of

living

Antonella Picchio

Introduction

The statistical quantification of the unpaid work of social reproduction requires a conceptualisation of the economic system capable of containing it, taking account of its dimensions and its quality. Unpaid work involves the upkeep of living spaces and domestic goods, care of the health, education and psychological needs of family members, and the maintenance of social relationships. According to statistical classifications, it is divided into domestic labour (transformation of goods and care of living spaces), care of persons, and work required to link the domestic and public spheres arising from family responsibilities (e.g. taking children to school, paying bills). Data show, at international level, that these three components may change in weight, but the total does not alter. For example, in some types of family less time is spent preparing meals and more time is spent on childcare and servicing (e.g. taking them to the swimming pool, to school).1 Quantitatively, unpaid work, measured in units of time, in Italy and in other countries, slightly exceeds the total amount of paid work done by men and women, while, qualitatively, it is essential for the maintenance of the system as a whole. Thus, this work constitutes one of the major aggregates of the economic system. In its specific activities and their relative weights it reflects historical and cultural changes; its basic functions, along with public services and the provision of market goods and services, are central to the process of social reproduction of the population.2 Unpaid work is essential, both for those who benefit from it and for those who do it; it is part of the basic organisation of living conditions, and it reflects historical relationships between men and women, classes and generations.

Data on the use of time show that it is simplistic to believe that children and the old are the only ones to benefit from domestic and care work. Behind these groups are stronger ones, especially adult men, for whom women's housework and care is a basic support for living, not only at times of crisis but also, and especially, in normal, everyday life. Daily reproductive activities are interwoven with the labour market which regulates mobility, times and conditions of paid and unpaid work. The division between men and women of the unpaid work of social reproduction within the household constitutes the kernel of gender difference. In fact the data show a macroscopic difference in men's and women's use of time, which in Italy is greater than in other countries (Picchio 1992, 1999; Sabbadini and Palomba 1995; Addabbo, Chapter 2, this volume).

This study, while adopting gender difference as a tool of analysis, uses the experience and awareness of this difference to reveal some basic aspects of the economic system, and the persistence of certain profound tensions within it. The analytical link between gender difference and the economic system is indicated in the living conditions of the working population and in their role as social capital. The argument for integrating the unpaid work of social reproduction into the view of the system, and hence into macroeconomic analysis, is here articulated in three circular-flow diagrams linking, first, families and firms, and then families, firms, the state and civil society.3

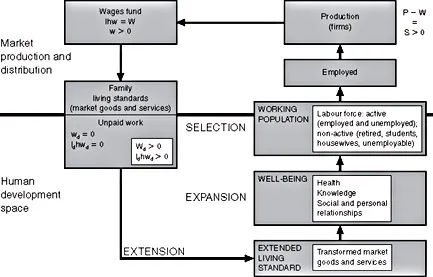

The major functions of reproductive labour at systemic level are to ensure the quantity and quality of the population: (1) to extend income from a monetary value to a standard of living that includes the transformation of goods and services through unpaid domestic labour; (2) to expand the extended standard of living into a condition of well-being which involves the enjoyment of specific, conventionally established levels of education, health and social relations; (3) to sustain the filtering process of the labour market (young and old, women and men, able and non-able); in this case, the unpaid work done in the home serves to underpin the selection of individuals for the labour market and the personal capacities used. Thus, unpaid work both materially and psychologically facilitates the processes of adaptation to the waged labour market, absorbing its tensions.

From the statistical point of view, extending the definition of income means counting unpaid work as one of the components of wealth. A grilled steak is more enjoyable and digestible than a raw steak; how it is cooked and how it is eaten depends on the cultural and historical context, but cooking meat is as much a part of economic reality as producing and selling it, all the more so as the one who produces (the waged worker) needs to eat enough, if possible in company, to be productive. Hence the extension affects both the accounting of a contribution to the production of wealth and the accounting of a cost necessary to produce adequate living conditions for labour efficiency. The absence of a commercial exchange in the case of socially reproductive work in the family has made a basic contribution to social wealth invisible, and has also obscured an important part of the costs of production.4

Whereas extension takes account of the quantitative aspects of the unpaid work of reproduction, adding these to monetary income to define the standard of living in terms of goods and services in their effective form, the expansion of the standard of living (as an extended bundle of goods and services) to include well-being takes account of the qualitative aspects of the work of social reproduction, and recognises the change of priorities and direction inherent in caring for people. That is to say, the primary aim of this work is the well-being of persons in terms of their quality of life. This is a material, social and cultural process based on trust, affection, friendship and social relations, which requires a sense of responsibility in order to achieve results. The expansion of income into well-being depends on actions and practices directed towards the well-being of persons. This perspective, as in the case of the approach used by Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum (Sen 1987, 1993; Nussbaum 2000), involves a change of priorities and direction: instead of using human labour as a means of valuing commodities, we use commodities as means in a multidimensional process of social reproduction at individual and collective level. This reversal has been analysed by Amartya Sen in a microeconomic context focusing on the actual freedom of individual non-utilitarian choices in given social contexts.

In this study, on the one hand, we make unpaid reproductive work visible; on the other hand, we locate well-being in a macro surplus approach and see it as a state within a process of social reproduction. In this approach, the exogenous distribution between wages and profit is centred on the very tensions between the living conditions of the working population and profit accumulation (Picchio 1992, 1998, 2000). Thus we follow a macroeconomic approach in which well-being is conceived of not in terms of individual choices, but as part of a structural framework that includes the material processes of production, distribution and exchange of wealth together with the process of social reproduction of the working population. Inserting an inherently institutional, historical and symbolic process such as that of social reproduction into the basic structure leads to radical modifications in the way the whole system is conceptualised. Moreover, class tensions are seen as centred on the historical social quality of the relationship, and the interaction between working and living conditions of waged labour.

Finally, the work of reproduction — besides making the living conditions of the working population sustainable — facilitates the functioning of the filter through which the population gains access to wages through the labour market. This involves a great flexibility of adaptation. At present, for example, in a context of variable work hours, increasing geographical mobility and intermittent access to wages, the family acts more and more as a filter compensating between disposable incomes and aspirations to socially adequate standards of living and rising expectations.

Important information on current changes in the functioning of the labour market as a filter of access to income may be found in the European Community Household Panel (ECHP) in which one can study and make comparisons among European countries with regard to changing types and distribution of incomes, rates of poverty, long-term unemployment and levels of family satisfaction. Changes in access to the labour market are combined with changes in the form of labour contracts. Among other things, the Panel's data show an increasing tendency towards workers being trapped in low wages and a growing rate of poverty within waged labour (Lucifora 1997). There is also a rise in the rate of dependency in terms of the number of people dependent on one wage. The growing tension within the family between the distribution of income and living standards, rooted in habits, tastes and social conventions, suggests that current restructuring in the labour market and welfare systems is being translated into an increased burden of unpaid work mostly done by women within the family. Nevertheless, economic policies devote very little attention to the problem of the adequacy of income with respect to conventional living conditions, and this fact leads, in present structural adjustments, to an intensification of unpaid labour that hides a withdrawal of firms and the state from their social responsibilities towards the quality of life.

Although research on family incomes explicitly studies the contributions made by different family members, the contribution of reproductive work continues to be ignored. In its questionnaire the European Panel asks one question about the care of the respondent's own children and about the unpaid care of other people's children, and one question about the daily unpaid activity of attendance on elderly, ill or disabled people. These two questions belong to a group of seven under the title ‘Responsibilities and social relations’. While recognising that the questions are burdensome in terms of survey costs, we must note that in other areas the questionnaire goes into greater detail — for example, there are twenty questions on courses of study. This difference in the amount of attention indicates that only professional training and education are considered, not the long and delicate process of formation of individual capabilities. This takes place mostly in the family, and serves increasingly as the basis of working capacities, especially in new jobs with a high relational content.

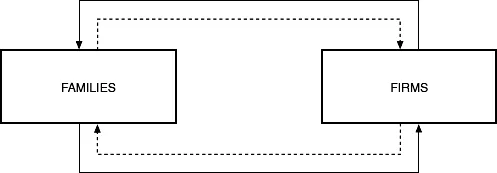

One way of beginning to break this analytical ground is to insert the great mass of unpaid labour of social reproduction into the basic analytical framework of the economic system. We can begin with a diagram, usually used in economics textbooks, here called the ‘simple co-operative circular flow’, which shows a relationship of circular interdependence between families and firms (Figure 1.1). In this circular flow are shown relations of exchange, both monetary and real: the firms buy labour and sell goods, the families provide labour and buy goods. It is assumed that this flow is reproduced on the basis of co-operation between the two institutions for the reciprocal interdependence of their interests.

The first step is, then, to extend this circular flow to include unpaid work of social reproduction, in its quantitative and qualitative aspects (Figure 1.2). Using data on unpaid work one can study the distribution of work within the family, and ‘extend’ the notion of living conditions now seen as the result of a process that uses market and non-market goods and services and unpaid reproductive work. This process operates in social contexts, given in historical time and geopolitical space, which define adequate standards of living, and the social norms that regulate the division of labour and

Figure 1.1 Co-operative flow.

personal responsibilities. The extension leads us into a space defined as human development (Figure 1.2). Using this concept of ‘human development’ one can carry out measurements which do not necessarily overlook the complexity of the process of social reproduction, and which make it possible to deal with some of its dimensions. This is done partly in the UNDP Human Development Reports, both in their indexes and in their indicators of living conditions. Here, we propose to extend the human development approach to include unpaid labour and to place it in a classical political economy macro approach. In doing so we juxtapose it to a neoclassical analytical framework that is basically ahistorical and spatially non-specific, with human subjects

Figure 1.2 Extended living — standard flow.

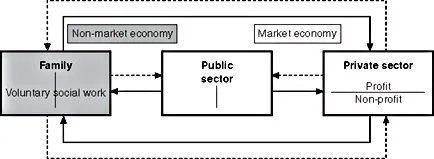

Figure 1.3 Social wealth flow.

freed from bodily needs. Thus conventional necessities are treated as simple ‘frictions’, i.e. non-necessities for the economic system. Moreover, in the neoclassical framework, social conventions and power relationships may be seen only as rigidities. In fact, they cannot be included as a general feature of the economic system without contradicting the basic generalisations of the theory embodied in its axioms. The problem is that in the process of social reproduction, by definition, conventions, personal interrelationships and social power relationships are fundamental persistent features. In the process of social reproduction the micro and macro aspects interact dynamically and cannot be separated, although there are many potential tensions which operate at both individual and collective level.

Finally, the potential tensions inherent in the distribution of work, resources and personal responsibilities are visualised in the third ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Routledge frontiers of political economy

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 1 A macroeconomic approach to an extended standard of living

- 2 Unpaid work by gender in Italy

- 3 Extended income estimation and income inequality by gender

- 4 Unpaid work and household living standards: equivalence scale estimation and intra-family distribution of resources

- 5 Unpaid work and household well-being: a non-monetary assessment

- 6 ‘Convenience consumption’ and unpaid labour time: paradoxes or norms?

- 7 Young people living with their parents: the gender impact of co-residence on labour supply and unpaid work

- 8 Unpaid and paid caring work in the reform of welfare states

- 9 The gender impact of workfare policies in Italy and the effect of unpaid work

- Index