- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book presentshuman ecology economics as a new and more comprehensive interdisciplinary framework for understandingworld conditions and human systems. This book helps economists rethink the boundaries and methods of their discipline - so that they can participate more fully in debates over humankinds present problems and on the ways that

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Human Ecology Economics by Roy E. Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Business allgemein. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The human ecology economics framework

Part I, comprising Chapters 1 and 2, provides a structural breakdown of “the human ecology” (see Figure 1.1); it argues for the new field of “human ecology economics”; and, as an introduction to the rest of this book, it discusses various topics that are addressed by this framework. In the editor’s view, human ecology can be defined as both (a) the interrelated world conditions and human systems, and (b) an interdisciplinary field or perspective that studies world conditions and human systems. “The economic system” is seen as a subsystem of “the human ecology.” Therefore, “economics” or “human ecology economics” (the study of the economic system) can be seen as a sub-field of “human ecology” (the study of the human ecology).

This approach is proposed to give economists maximum conceptual freedom to rethink the boundaries and methods of their discipline – so that they can participate more effectively in debates over humankind’s present problems and on the ways that they can be solved. Current global concerns addressed by this book include climate change, poverty and inequality, challenges of economic growth and development, resource scarcity, social strife, effectiveness of global institutions, financial crises, and governance crises. These interrelated risks threaten the sustainability of the global system as we currently know it.

Authors contributing to this volume are in general agreement that human ecology economics is a new framework to effectively respond to these global sustainability concerns, because, unlike other economic analysis:

- a very long run-time perspective is allowed;

- it allows use of the humanities and other social sciences including a formal role for belief systems, “ways of being,” and social agreements in the economic system;

- everything varies – including belief systems, ways of being, and social agreements – and is dependent on everything else in complex, coevolutionary feedback processes;

- global systems are emphasized; and

- sustainability and other interdisciplinary issues are effectively juxtaposed with more traditional economic issues.

Part I also elaborates the various dynamic and evolutionary perspectives that “give life” to this human ecology economics structure. In this evolutionary process, clusters of new technologies, leading industrial and commercial sectors (currently the post-1973 information-industries), and supporting institutions allow “long-waves” of economic growth, which coincide with political leadership by the successful nation or nations (currently the U.S. and others). Periodic “clashes of civilizations,” as well as the rise and fall of economies, are explained by these processes. While involving all structural components of the human ecology (as per Figure 1.1) in his analysis, in Chapter 2 George Modelski develops the dynamics of this human ecology approach, including Darwinian “human species” processes of search, selection, cooperation, innovation, reinforcement, etc. The reader is allowed a more comprehensive and long-run understanding of economic change compared to the growth and development models found in contemporary literature.

1 A human ecology approach to economics

Roy E. Allen

Introduction

A search for “human ecology” on the Google search engine produces an overwhelming 55 million results. A more traditional academic search, at the University of California, Berkeley library produces 903 references, which are scattered in various libraries ranging from Bioscience to Business and Economics and Environmental Design. Textbooks proposing to summarize this field include the early environmental-conservationist effort Human Ecology: Problems and Solutions (Ehrlich et al., 1973), and the recent Fundamentals of Human Ecology (Kormondy and Brown, 1998). The former focuses on “the biological and physical aspects of man’s present problems and on the ways that they can be solved,” (p. v) and the goal of the latter “is to present the fundamentals of ecology and their application to humans through an integrated approach to human ecology, blending biological ecology with social science approaches,” (p. xvii).

Much of this literature arose out of the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and gained breadth through recent explosions of interdisciplinary activity within academic institutions. At the College of the Atlantic, Maine, founded in 1969, the only degree offered to students is in human ecology, “which indicates that students understand the relationships between the philosophical and fundamental principles of science, humanities, and the arts.”

Discussions of “human ecology” often include an important role for culture – as when anthropologists such as Brown (ibid.) handle the subject. In Human Ecology as Human Behavior: Essays in Environmental and Developmental Anthropology (Bennett, 1996) the author finds that:

“human ecology” is simply the human proclivity to expand the use of physical substances and to convert these substances into resources – to transform Nature into Culture, for better or worse. . . . Humans exploit and degrade, but they also conserve and protect. Their “stewardship” refers to constructive management of Nature, not cultural determinism.

The author’s use of the term, as developed in this book, allows for most of these approaches, including a major role for the humanities and the interdisciplinary social sciences. The “structural overview of human ecology” developed in this chapter can be used to sort out various perspectives, rather than limit the reader to one or the other. Subsequently in this chapter, the author proposes a definition of “the economic system” as a subsystem of “the human ecology.” Therefore, “economics” (the study of the economic system) can be seen as a sub-field of “human ecology” (the study of the human ecology).

This approach is proposed to give economists maximum conceptual freedom to rethink the boundaries and methods of their discipline – so that they can participate more fully in debates over “humankind’s present problems and on the ways that they can be solved.” Contributing authors in this book both identify problems in our economic system, and help to find solutions. Along the way, a “human ecology approach to economics,” or “human ecology economics” seems to find its justification.

The human ecology approach to economics developed by the author is similar to the relatively recent field of “ecological economics.” The latter has been given its impetus by the 1989 journal of the International Society for Ecological Economics, Ecological Economics, and various publications including the first real textbook, An Introduction to Ecological Economics (Costanza et al., 1997). Earlier origins of this field are discussed by Juan Martinez-Aler in Ecological Economics (Martinez-Aler, 1987).

The emphasis on human ecology combined with economics brings the “humanities” as well as the physical science-based field of ecology to the study of economics, and the framework is thus broader than ecological economics. For example, as argued in Chapter 9, ideologies and “ways of being” (as defined through fields such as philosophy, psychology, sociology, religious studies, literature, etc.) are important structural components of the economic system, and they are not given sufficient attention within the fields of ecology, economics, or ecological economics – although a recent article in Ecological Economics did call for greater attention to the role of ideology and values (Söderbaum, 1999). Clearly the field of ecological economics could give greater importance to the role of intangible beliefs, values, various social constructs, etc., and how these intangible conditions co-evolve with tangible resources and populations, as per Norgaard (1994), but then, what we would seem to have is “a human ecology approach to economics,” or “human ecology economics” rather than ecological economics.

A structural overview of human ecology

None of the 903 references to “human ecology” at the University of California, Berkeley, library cites the famous science fiction writer and social commentator H.G. Wells. Wells was one of the first to propose and develop this area of studies, and his articulation probably comes closest to the approach used here – given its emphasis on global economic and political processes. In an article in Harper’s Monthly Magazine in 1937 he notes:

But in view of the number of able and distinguished people we have in the world professing and teaching economic, sociological, financial science and the admittedly unsatisfactory nature of the world’s financial, economic, and political affairs, it is to me an immensely disconcerting fact that [Wells’] Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind, which was first published in 1932, remains – practically uncriticized, unstudied, and largely unread – the only attempt to bring human ecology into one correlated survey.(Wells, 1937, p. 472)

Well’s emphasis on a more interdisciplinary political economic approach responding to global concerns was complemented, before World War II, by various other earlier uses of “human ecology,” as nicely summarized in the free electronic encyclopedia, Wikipedia (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_ecology):

In the USA, human ecology was established as a sociological field in the 1920’s, although geographers were using the term much earlier. Amos H. Hawley published Human Ecology – A Theory of Community Structure in 1950. He dedicated the book to one of the pioneers in the field who had begun writing the work with Hawley, R.D. McKenzie. Hawley contributed other works to the development of the field. In 1961, an important reader, Studies in Human Ecology, was published.(edited by George A. Theodorson)

The issues that were important to H.G. Wells concerned “what is happening to mankind,” and he used “human ecology” to describe the interdisciplinary framework or field that might provide a forum for scholars to investigate these issues. In World Brain (1938), he noted that knowledge was becoming so fragmented, so intradisciplinary, so disconnected from the major problems of humanity, that it was proving less useful to policymakers. Speaking of the people in the League of Nations and Roosevelt’s “brain trust,” he thought they had “uncoordinated bits of quite good knowledge,” but they “knew collectively hardly anything of the formative forces of history . . . [nor of the] processes in which they were obliged to mingle and interfere.” His solution to this problem was the development of an encyclopedia as

the means whereby we can solve the problem of that jig-saw puzzle and bring all the scattered and ineffective mental wealth of our world into something like a common understanding, and into effective reaction upon our vulgar everyday political, social and economic life.

Wells thought that human ecology should bring together various bodies of scholarship: “flowing into the problem of human society [would be] a continually more acute analysis of its population movements, of its economic processes, of the relation of its activities to the actual resources available.”

Based upon these issues raised by Wells, and based upon subsequent, similar writings of economists such as Kenneth Boulding, this book proposes “a human ecology approach to economics.” Boulding is acknowledged here especially for his work in the area of General Systems Theory, including the Society for General Systems Research. His essays in this area are collected in a 1974 volume (Boulding, 1974) and elaborate on many of the issues raised in this book, especially notions of what constitutes a social system. This book can be thought of as an update to Boulding’s work – it reconstitutes some of the systems terminology of his 1974 volume as well as Ecodynamics: A New Theory of Societal Evolution (Boulding, 1978), and applies its framework to a host of contemporary issues: economic globalization and development; world energy resources and climate change; population trends and food challenges; money, capital, and wealth creation, transfer, and destruction; ideologies, mythologies, and “ways of being” in the economic system; evolution and innovation in the economic system including the role of institution and organizations; the rise of the “new economy”; and so on.

Human ecology can be defined as both (a) the interrelated world conditions and human systems, and (b) an interdisciplinary field or perspective which studies world conditions and human systems. As a body of studies, it seeks to coordinate previously disconnected knowledge, and make that knowledge available for a wide variety of practical purposes. If “interdisciplinary” means “activities taking place between well-identified disciplines,” then human ecology is also transdisciplinary or non-disciplinary, because it does not assume that established disciplines are sufficiently comprehensive building blocks to frame the analysis. Phenomena-based and issue-based approaches are used as well as discipline-based approaches. Human ecology is also multidisciplinary, because it uses elements of various disciplines to build realistic models.

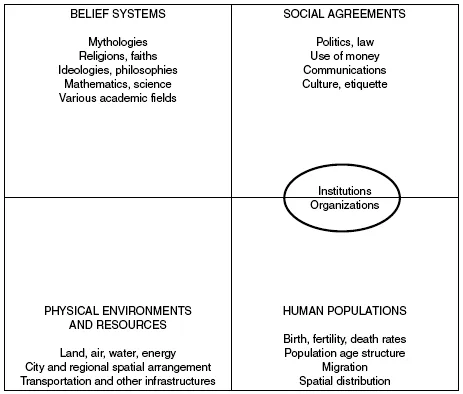

I propose various structural components or building blocks of human ecology. Perhaps the most fundamental components are human populations, belief systems, social agreements, and physical environments and resources. From these basic structural conditions other structural conditions emerge, such as organizations, institutions, and for the purpose of this book, economic systems. This structural identification or taxonomy is not meant to be the only way to characterize the human ecology, but rather a helpful starting point for discussion.

Figure 1.1 organizes the four basic structural conditions into quadrants. “Belief systems” is shown in the upper left quadrant, which can be defined as “ways of organizing alleged truths and convictions.” Examples include, but are not limited to mythologies, religions, faiths, ideologies, philosophies, mathematics, science, and various academic fields. Social agreements, shown in the upper right quadrant, can be defined as “the structure that humans impose on their interaction.” Social agreements usually reduce uncertainty; they are the formal and informal “rules of the game.” Examples include, but are not limited to: politics; law; use of money; communications; and norms of culture and etiquette. In the lower right quadrant is “human populations” with characteristics that include birth, fertility, death rates, population age structure, migration, and spatial distribution. In the lower left quadrant is “physical environments and resources,” which includes land, air, water, energy, city and regional spatial arrangement, transportation and other infrastructures – both natural endowments as well as human-built.

Figure 1.1 Structural conditions in the human ecology.

The four basic structural conditions in the human ecology can also be more directly combined with each other to form new structural conditions. For example, as shown in Table I, “organizations” can be defined as human populations bound together by common social agreements – examples include firms, trade unions, political parties, and regulatory bodies. Of course, organizations use, and interact with, belief systems and physical environments and resources, but these interactions are not generally necessary in order for organizations to exist as legal entities. In common usage, “institutions” are sometimes closely synonymous with “organizations,” and sometimes more synonymous with “social agreements.” A useful definition for human ecology (similar to social agreements) from Douglass North is: Institutions are the rules of the game – both formal rules and informal constraints (conventions, norms of behavior, and self-imposed codes of conduct) – and their enforcement characteristics (North, 1997, p. 225).

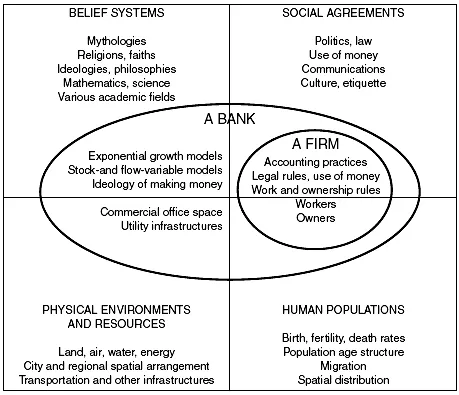

Furthermore, each of the sub-elements in Figure 1.1 can be broken down into sub-sub-elements. For example, maybe we want to understand what a commercial bank is. With regard to belief systems, perhaps a bank relies upon the mathematics of exponential growth (such as the law of compound interest) and stock-and-flow-variable models, rather than the entire field of mathematics; and, maybe there is mostly an ideology of making money rather than other faiths or belief-system orientations. In Figure 1.2, these sub-sub-elements of belief systems are shown separately in the belief systems quadrant within the circle called “a bank.” From the physical environment and resources, perhaps a bank requires commercial office space and utility infrastructures, which are therefore shown separately in that quadrant. Sub-sub-elements from social agreements and human populations are also identified, and when all sub-sub-elements are bundled together, we have the structure of “a bank.” And what type of organization (human population bound by social agreements) is a bank? As shown in Figure 1.2, when the bank-structural-elements from human populations are bundled together with the bank-structural-elements from social agreements, then the new bundle is what we commonly call “a firm.”

Figure 1.2 Structural conditions in the human ecology: a bank.

Based upon these structural components of the human ecology, Figure 1.3 shows a possible bundle of structural elements that might be used to describe the economic system. In this scheme, economic systems are shown to have important elements from each of the four basic structural conditions. Regarding belief systems, the human ecology approach proposes that the economic system relies heavily on mathematics, science, (traditional textbook) economics, ideal, faith, and myth among other factors. The types of social agreements, which are important in the economic system, include, but are not limited to, the use of money, policy, regulation, networks, and culture. From human populations there are workers, entrepreneurs, consumers, and policymakers, among others, and from physical environments and resources there are commodities, infrastructures, and natural resources among other tangible goods and structures.

Compared to most economics literature, which minimizes the importance of belief systems, social agreements, institutional change, and the integrity of physical environments and resources, the human ecology framework might allow for a more comprehensive identific...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Part I The Human Ecology Economics Framework

- Part II Globalization and Development

- Part III Money, Capital, and Wealth in the Human Ecology

- Part IV Global Concerns, Ways of Being, and the Future