![]()

1 Hegemony and the Operation of Consensus and Coercion

Richard Howson and Kylie Smith

Hegemony and the Asia-Pacific

This volume responds to the recent explosion of interest and research on hegemony in the social, economic, and political sciences. However, its approach to hegemony differs from that which is evident in much of the literature. First, it is an approach that recognises the 'complex' nature of hegemony at both the theoretical and empirical levels. Second, it applies this complexity to the Asia-Pacific region because it, more than any other region in the world, has and continues to experience momentous changes at the social, economic, and political levels. However, while the operation of hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region has attracted investigation and discussion, most of this work presents a picture of regional economic, social, and political operations as becoming ossified to Occidental or, more specifically, US domination within a zero-sum game. This obfuscates the many sociohistorical antagonisms within the hegemonic process. This volume will present theory illustrated by empirical case studies that highlight these antagonisms to show that hegemony is never simply domination but a far more complex operation of coercion and consensus.

Today, the Asia-Pacific represents the most significant region in terms of future global social, economic, and political development. As Scalapino (2005, 231–240) argues, the twenty-first century will be one of momentous change, both within the nations of the Asia-Pacific and in their international relations. This is exemplified in the significant economic successes of some nations juxtaposed with the abject failure of others. In addition, the region continues to be drastically altered by the combined forces of social, economic, and political instability, as well as terrorism and dictatorships. These factors are important in themselves but become even more so when operating in a region that contains world powerhouses of people such as China and India that contain no less than one-third of the world's population—as well as powerhouses of social, economic, and political relations of force such as Japan, China, Indonesia, Australia, and Malaysia. The region is also home to some of the poorest and most oppressed nations, including Papua New Guinea, India, and Vietnam. Thus, the Asia-Pacific region becomes one of great significance for those concerned with exploring the space between domination and aspiration, regression and progression or, in other words, the development and complex operation of hegemony.

However, there is often great confusion about what constitutes the Asia-Pacific region (Connors, Davison and Dorsch 2004) and even some debate about whether the Asia-Pacific constitutes a region at all, given its diffuse geography, ethnicities, and cultures, as well as its social, economic, and political inequities. While this debate has some merit, it is this fluidity and dynamism that is precisely the characteristic or thematic that binds the Asia-Pacific into a region for the purposes of this volume and, more importantly, makes the Asia-Pacific an important focus for the study of hegemony. As the chapters that follow will show, the nations of India, China, and then Japan to the northeast; the ASEAN nations of Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia; and Papua New Guinea and Australia all represent sociohistorically important case studies that shed new light on the Asia-Pacific as well as on the constantly evolving global 'puzzle.'

Key Concepts in the Theory of Hegemony

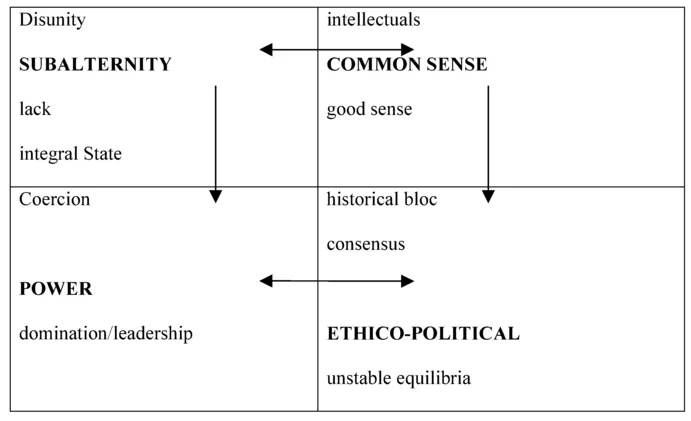

The following section briefly presents and describes the set and subsets of key concepts that will be drawn from the theory of hegemony that, in turn, will form the basis for the analyses in the later theoretical and empirical chapters. In the first instance, a set of four key concepts is abstracted, including: subalternity, common sense, power and ethico-political. There is no deliberate intent to project the set of framing concepts and the subsets of concepts as existing and operating autonomously, either within the theory of hegemony or, indeed, in this volume. Rather, Figure 1.1 presents a conceptual map showing some of the key concepts and their interconnections—that is, the lines of relationships that connect them within the theory of hegemony.

Presentation of these concepts as distinct serves purely analytical purposes. However, it is only by abstracting each concept from the theory of hegemony that we are able to develop a framework that: (a) shows the nature and operation of each concept, (b) shows the relationship these concepts have with each other as well as the other related concepts, and most importantly, (c) enables their application to empirical analysis and, through this, the explication of the complexity of hegemony.

Using Figure 1.1, the point of departure for our study of hegemony is not the concepts of power and domination but, rather, the concept of subalternity, which for Gramsci represented a way of expressing a 'lack' of 'political autonomy' (1975, Q25§4). In other words, subaltern social groups, which may represent slaves, peasants, religious groups, women, different races, and the proletariat (Gramsci 1975, Q25§1, 4, 5 and 6), are already subordinate because their experience is the negation, redefinition, and then incorporation of their needs and desires into the activities and interests promoted by the elites. Thus, hegemony is not an immediately engaging set of practices and beliefs. It is never imposed aprioristically but is always developed within the social, economic, and political relations of a particular situation. Therefore, its study cannot begin with, and then focus only on, power but rather with the relationship between powerlessness and power. So to really grasp the theoretical and empirical importance of sub-alternity to hegemony, requires analytic engagement with the concept of Integral State.

Figure 1.1. A conceptual frame.

As a broad structure, the Integral State is the dialectical synthesis of both political society and civil society and represents hegemony as never simply the independent operations of political power. So, if in fact subalternity expresses a lack of political autonomy—that is, the ability to use politics to promote one's own interests—then the primary sphere of existence and operation for subaltern groups is civil society (Gramsci 1971, 52). Within civil society there is no single subaltern group into which all subaltern groups are naturally subsumed, even though there is a common equivalence about what constitutes subalternity that is, precisely, a disconnection from or lack of political autonomy. This 'lack,' as Gramsci (1975, Q25§4) refers to it, ensures that subalternity is locked to civil society and, more importantly, that civil society is marked by antagonisms and disunity, whether they are organized around 'party, trade union [or some other] cultural association' (Gramsci 1975, Q25§4). Further, subalternity will remain a disunited antagonism attached to these various forms of organization until they become unified, and this unification cannot occur and become power until they become a 'State' (Gramsci 1975, Q25§5).

Within the process of constructing hegemony, there is an immediate and important nexus between subalternity and common sense. This nexus is central to explaining how lack of political autonomy remains a reality for subaltern groups, but more importantly, how this lack is based on the disunity that prevails in civil society that, in turn, enables a group or set of interests to dominate the Integral State. Gramsci (1971, 199, 326) makes clear that common sense is 'the traditional popular conception of the world' and cannot constitute an 'intellectual order' because it cannot produce a 'unity within an individual consciousness, let alone collective consciousness.' In other words, common sense is what defines and describes the everyday life and beliefs of a particular subaltern social group. Common sense demands 'conformism' to the group's particular traditional practices and beliefs (Gramsci 1971, 324), which in turn leads to a fragmentation of civil society along the various and often competing lines of common sense ascribed to by subaltern groups. Common sense is antithetical to 'critical elaboration' because only critique enables coherency and, ultimately, unity (Gramsci 1971, 324). The moment of critique emerges from consciousness of oneself. But rather than focusing this consciousness on one's own or group's immediate interests, understood as 'corporativism' (Gramsci 1971, 255–256), critique must bring about consciousness that is knowledge of the broad subaltern experience in both its social and historical context; that is, critique uses the past to inform the future but is always mediated by the present.

While Gramsci was critical of common sense because on its own it was incapable of producing collective action, he did not completely dismiss its efficacy. In fact, throughout his preprison writings, which culminated in the unfinished 1971 essay 'Some Aspects of the Southern Question,' there is the development of a strategy for hegemony that gives recognition to common sense but that also takes seriously its reconfiguration and elaboration through practical ideas such as 'hegemony of the proletariat,' which at the time were striking and radical (Gramsci 1971, 339–343). This emphasis was not lost in the Prison Notebooks either, and here Gramsci gave a new complexity to hegemony. In other words, hegemony as the highest synthesis1 was marked by an Integral State that was itself based on a unified civil society and where political lack was minimised. To achieve this required an understanding of how subaltern social groups, in all their diversity, think and act through their own common sense. Through this knowledge, Gramsci argued that a subaltern group can become a leading group by developing its own practices and interests in such a way as to incorporate the various other expressions of common sense to produce a new 'good sense.' In other words, subalternity as an identity and practice has inherently the potential to critical elaboration and, therefore, the progression from common sense to good sense, from disunity to unity, and from hegemony marked in the final analysis by dogma and coercion to hegemony marked in the final analysis by openness and consensus.

The key mediator in this process is the 'organic intellectual' (Gramsci 1971, 6), whose task it is to produce progressive self-knowledge through education (Gramsci 1971, 238–239). Organic intellectuals in this sense are differentiated from 'traditional intellectuals' in that 'organic' signifies the mass-intellectual nexus, so that the 'ideological' function of traditional intellectuals is exposed. Organic intellectuals are informed by, and informing of, the mass, whereas traditional intellectuals serve to disarticulate the mass from power, from hegemony (Gramsci 1971, 12–14). The movement from common sense to good sense, or the development of a new hegemony, involves the organic intellectual in the reconfiguration of power so that it organically can only develop through a 'war of position' (Gramsci 1971, 229–239). However, explicating the operation of power through the theory of hegemony and applying it to social, economic, and political reality is not so easy. In fact, it is one of the most difficult concepts to explain because it is precisely power that must be reconfigured through a war of position to produce hegemony—but the reconfiguration does not always happen in the same way or with the same outcomes. Nevertheless, it is still referred to as hegemony.2

In much of the secondary literature that employs or analyses the concept of hegemony, power is conceptualized and presented as an asymmetrical politico-economic operation that leads ineluctably to domination. Further, the State is confined to political society and its task is to impose the interests of the capitalist class over civil society, often silently and with stealth. The crucial consequence of this view of power is that the resultant critique emphasises the coercive nature of the State, usually through close and critical analysis of the political economy inherent in a particular situation. In other words, economics is seen to give form to political society so that the nature of the critique of power is constrained to a 'politico-economic' operation (Gramsci 1971, 16). However, to assume that this analysis of power yields a complete picture of hegemony is wrong. Crucially, it fails to recognise the vast resources that must be mobilised in civil society—such as the media, education, the family, religion, law, communities, and markets—to ensure that the political economy can be and is maintained. Thus, to engage in a complex understanding of power operationalised in hegemony, there must also be a focus on resistance, and to see how this operates we must elaborate the nexus of subalternity and common sense to now include power.

In the theory of hegemony, when Gramsci speaks of the State acting as domination, the State has incorporated certain corporatist interests and exercises its power to maintain these interests by keeping the subaltern social groups fragmented and passive within civil society. This represents a situation in which the definition and expansion of hegemony is enabled by the State's ability to fragment the operations of civil society and therefore its influence on political society. In the chapters that follow, it will be shown that this disconnection operates around certain 'hegemonic principles' (Howson 2006, 23) that are central to the definition and expansion of the hegemony.3 Further, when hegemony dogmatically upholds and protects its hegemonic principles, it is at this moment that the hegemony closes down and becomes ossified. It is also at this moment that it must resort to coercion rather than consensus. The consequence is that hegemony must now manage a diminishing legitimacy about its hegemonic principles that has become a 'crisis of authority' (Gramsci 1971, 210).

By emphasising crisis, Gramsci shows that at the centre of hegemony is power operating with legitimacy and that, in fact, this authority is 'dying' (Gramsci 1971, 276). In other words, the authority of the State to negate, redefine, and then incorporate the needs and desires of subaltern groups into the activities and interests of the leading social group is no longer based on progressive but regressive forces. As a consequence, hegemony is marked by a State that is unable to lead through moral and intellectually based strategies of consensus but can only dominate and therefore 'exercise coercive force alone' (Gramsci 1971, 276). This gives rise to a 'dominative hegemony' (Howson 2006); that is, when authority has lost legitimacy and can only operate as power, hegemony becomes regressive because the State must engage a strategy of coercion to restore its legitimacy and, thereby, its authority. This begins with the mobilization of the traditional intellectuals (Gramsci 1971, 6). The immediate task is to reinstate the disunity of civil society by undermining the authority of the organic intellectuals and the development of a comprehensive social and historical critique of authority—in other words, to undermine the development of a 'war of position' into various ineffective 'war of movements.'

The interpretations of hegemony as domination tend to equate State power with authority and ignore the importance of legitimacy. In functional terms, power is presented as disconnected from civil society and the operation of legitimacy. If hegemony was to be left within this framework, all following analyses would lack the complexity needed to recognize the struggles over legitimacy in which the progressive and empowering moments and efforts are always a central part. In effect, hegemony would emphasise power but de-emphasise legitimacy. The consequence is that analyses lose sight of hegemony as 'unstable equilibria' (Gramsci 1971, 182); that is, they lose sight of the historical and social nature of hegemony.

To begin to recognise the complexity of the theory of hegemony is to begin to recognise inter alia the hegemonic nexus between power and legitimacy in the production of authority. This exposes the reality that authority expressed as domination can never exist as legitimate—that is, with full consensus. Subalternity is evidence of this impossibility. In fact, hegemonic authority exercised as domination must impose coercion at some level of intensity and focus so as to ensure the dominant interests are protected. Gramsci (1971) argues that hegemony always exists between the politico-economic level of reality—that is, where corporativism creates disunity of interests, enabling domination to act as the unifying force—and the ethico-political, that is, where the plurality of interests operate through moral and intellectual hegemonic logic as a unstable equilibria and leadership acts as the unifying force.

The concept of ethico-political is central to Gramsci's project to give the philosophy of praxis, or Marxism, a 'real' philosophy, and the central philosopher in this project is Benedetto Croce. In fact, ethico-political represents a Crocean concept that Gramsci brings to the theory of hegemony and, in so doing, it becomes both 'fundamental to the notion of hegemony and....the historical bloc' (Boothman 1995, 328) but also its organic and progressive objective (Finocchiarro 1988, 23). However, a crucial feature of ethico-political as a hegemonic expression is that its achievement is always grounded in a dialectical methodology. For Gramsci, the dialectic method follows prima facie Georg Hegel's thesis/antithesis/synthesis model, but more importantly, underlying Gramsci's Hegelianism is a complex engagement with Croce's own dialectic method. Gramsci's engagement with Croce is complex because it is as much a critique of Croce as an endorsement in so far as it critiques Croce's interpretation of Marxism as lacking any real philosophy and simply representing the expression of socio-political action while accepting the absolute historicist nature of Croce's (1951, 18–19) philosophy (Finnochiaro 1988, 18–19). But Gramsci questions the historicist dialectical methodology Croce puts forward because as a process it involves the historical evolution of four essentially distinct forms of practice and beliefs that are described by Finnochiarro (1988, 16) as: expressive cognitive acts (identified with art), ratiocinative cognitive acts (identified with philosophy), general volitional acts (identified with economic practice), and moral volitional acts (identified with moral action)...