![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1 Greece

An introduction to patterns of EU

membership

Dionyssis G. Dimitrakopoulos and

Argyris G. Passas

This book examines the behaviour of the Greek state as a member of the European Union. It seeks to identify the factors that affect the way in which the Greek state has participated in the EU process of policy formulation and implementation since 1981. In that sense, it is not a history (Kazakos 1994) of Greece’s attempt to join the then European Economic Community (EEC), which started on 8 June 1959 when Greece applied for an association agreement.1 Neither is it an account of a specific key event, although a number of them occurred since January 1981, when Greece became the tenth member of the then European Communities. Rather, it is an attempt to identify and analyse the dynamics of the involvement of the Greek state in the EU policy process and to do so from the perspective of public policy.

Greece is one of the smaller Member States and one whose post-1945 history has not – unlike that of France and Germany – been at the heart of the process of European integration. Nevertheless, the analysis of its membership from the perspective of public policy is fascinating for a number of reasons. First, for about ten years Greece had behaved as an awkward partner and came to be seen as the ‘black sheep’. Since this is not the place to analyse the specific instances that exemplify this pattern, two examples will suffice. On the one hand, the ‘buy Greek’ policy pursued by Greek governments in the 1980s covered both the private and the public sectors (Dimitrakopoulos 2001) despite increasing attempts on the part of the then EEC to liberalise public sector purchasing. On the other hand, Greece was perceived during the early 1980s as ‘the maverick of EPC’ (Regelsberger 1988: 35), i.e. a country that adopted ‘atypical’ positions on various international issues of major European concern. This was exemplified by its refusal to explicitly denounce the Soviet Union in the South Korean Boeing affair (de la Serre 1988: 204).

Second, the 1990s saw a partial gradual change on the part of the attitude – and to some extent the effectiveness – of the Greek government vis-à-vis the EU. This process culminated in two events of major strategic significance: qualification for the third and final stage of EMU and the adoption of the euro (Andreou and Koutsiaras, Chapter 7 in this volume) and the successful attempt to place Greek relations with Turkey in the context of the EU (Couloumbis and Dalis, Chapter 6 this volume).2 In short, although the widely held belief that Greece is a laggard in a number of policy areas is not inaccurate, the pattern of Greek membership of the EU is much more complex, not least because it contains ‘success stories’. Why has Greece succeeded in some of its objectives but failed in others? What accounts for this variegated pattern of membership? This is what this book is about. It relies on the logic of ‘policy styles’ (Richardson 1982) and seeks to identify the extent to which membership of the EU has altered (or Europeanised) traditional patterns of policy-making.

The next section sets the scene by highlighting the broad patterns of Greek membership of the EU. The third section of this chapter presents the conceptual framework upon which this book is based. The final section describes the content of the chapters that follow.

Greece in the EU: patterns of membership

Formulation

The Greek institutional and organisational arrangements for the formulation of European policy and representation in the EU’s policy-making system is directly linked to not only the Greek government’s perception of EU membership and policies but also the inherent, traditional features and standard operating procedures of the domestic politico-administrative system. The former displays a smooth but clear shift – not least in the official political discourse – from a defensive, Greek-centred and financial perception to a more open and politically pro-European one. This became more apparent after Prime Minister Constantinos Simitis’ advent to power in 1996.

Policy formulation can be described as defensive, reactive and highly fragmented and lacking in terms of institutional memory, political continuity and predictability. It is a system couched primarily on informal, ad hoc practices rather than on institutionalised procedures even though formal arrangements actually exist. It depends on individuals’ skills and capacities and personal networks, as opposed to collective and visible institutional mechanisms and procedures, both at the political and administrative levels (Stephanou and Passas 1997). This undermines accountability and the systematic involvement of local public authorities and societal actors.

Three factors explain the Greek patterns of European policy formulation. First, there is a lack of clearly defined political orientations and policy priorities, especially in sectoral policies. In other words, there is lack of effective political leadership and steering capacity, which led Spanou to depict the Greek system as a ‘truncated pyramid’ (Spanou 2000: 161). Second, the Greek public administration is highly ineffective, centralised, fragmented and politicised (i.e. largely based on political patronage and clientelism) and has underdeveloped policy planning and design mechanisms and capacities. Finally, this administration operates in the context of a weak civil society and interest organisation system defined ‘as state corporatist, … an anarchic corporatist state or a case of limited but polarised pluralism’ (Tsinisizelis 1996: 244–9).

Implementation

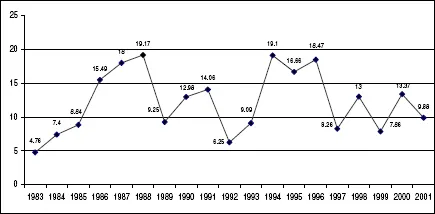

Greece is widely considered to be a laggard in the area of implementation of EU legislation. Although the implementation deficit – i.e. the discrepancy between the formally agreed policy objectives and reality at street level – is a systemic feature of all polities be they unitary or federal, and monitoring is a very complex process, the EU’s implementation record varies both across areas and Member States. Figure 1.1 illustrates the number of referrals of Greece to the ECJ as part of the total number of cases referred between 1983 and 2001.3

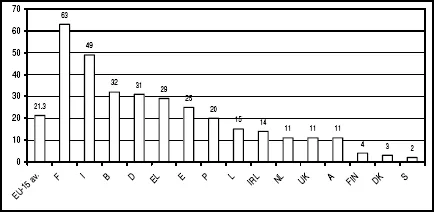

The pattern that emerges is dynamic in the sense that it changes over time but it is also revealing of the intensity of the problem in Greece. The extreme examples of 1988 and 1994 reveal that at some point in time Greece was involved in roughly one in five cases brought to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). If these can be considered as extreme cases, Greece’s average in the 1983–2001 period leaves no doubt about the intensity of the problem: 12.20 per cent of the total number of cases concern a small economy with a small population (11 million) although Greek representatives in the Council frequently manage to secure longer than average transitional periods. Figure 1.2 shows the number of single market-related infringement cases brought to the ECJ against Member States between 1 January 1995 and 31 August 2001 (European Commission 2001c: 12).

Figure 1.1 Referrals of Greece to the ECJ as part of the total number of cases referred, 1983–2001.

Figure 1.2 Number of single market-related infringement cases brought to the ECJ, 1 January 1995 to 31 August 2001.

The advent of the single market and more than ten years of direct involvement in the process of integration and the ‘socialisation effect’ that it brings about have not mitigated the apparent inability of the Greek authorities to cope with EU legislation. It is clear that the Greek score (29) remains significantly higher than that of other comparable Member States (e.g. Portugal) and the EU-average (21.3).

Explaining failure

Structural characteristics of the Greek state and historically defined patterns of political development are typically portrayed as the root causes of the inability of the Greek state to assume the obligations of membership in the short term and to play an active role in the process of integration in the long run. Diamandouros highlights the fact that despite two decades of impressive and unprecedented socio-economic change rates in the 1950 and 1960s, modernisation was impeded by three structural weaknesses (Diamandouros 1997: 25–7). First, the existence of a vindictive anti-communist state in the post-Civil War era relied on the systematic distinction between winners and losers with the latter being constantly excluded from the ever-expanding public sector. This led to the recruitment of civil servants on the basis of actual or presumed allegiance to the regime, i.e. on non-meritocratic criteria which easily bred corruption. Second, a particularistic – as opposed to universalistic – logic permeated the process of distribution of economic and social benefits in society. This in turn led to significant inequalities and prevented the emergence of societal checks on the growing, but lacking in legitimacy, state. Third, this process led to the fragmentation of the productive structures which necessarily relied on state protection. Extremely small and uncompetitive firms depended on state protection and illicit practices, tax evasion and corruption.

The Pan-Hellenic Socialist Movement’s (PASOK) electoral victory of October 1981 (i.e. just a few months after the country’s accession to the then European Communities) has to a large extent cemented contradictory sociopolitical patterns. On the one hand, it has enhanced the process of democratisation of the political system in the sense that large social strata that were previously excluded from the exercise of political power were now the dominant force. On the other hand, this landmark event also cemented the logic of clientelism and aversion to meritocracy. This was the basis of the large-scale redistribution that followed. The continuing weakness of civil society was both a product and a cause of this phenomenon. Pressure from Brussels in the area of economic reform seemed to increase reliance on the state for either privileged access to resources or protection from competition.

There is no doubt that these socio-economic and political patterns could not – and did not – provide the basis for the successful, or at least constructive, involvement of the Greek state in the process of European integration. Indeed, the dominant political discourse initially portrayed Brussels in adversarial terms, i.e. as a source of constraints on public policy-making and national independence. This defensive logic was further enhanced at the level of the Athenian bureaucracy (and its political leaders) by direct contacts with the institutions of the EC. A defensive, disjointed and reactive approach to agenda-setting and policy formulation were matched by lax attitudes towards implementation (Spanou 1998; Dimitrakopoulos 2001) and the strong emphasis on the extraction of funds.

However, this short account has two weaknesses. On the one hand, it is static and, therefore, does not account for change over time.4 On the other hand, it does not account for differences between policy sectors. The aims of the next section are twofold. First, it seeks to place the present study in the context of the burgeoning literature on the so-called Europeanisation of the nation state that is the direct product of membership of the EU. Second, it seeks to provide a framework for the discussion of the patterns of Greece’s membership along sectoral lines of differentiation.

What is Europeanisation and how does it operate?

Europeanisation

The use of the term ‘Europeanisation’ has become very widespread (Green Cowles et al. 2001; Héritier et al. 2001; Knill and Lehmkuhl 1999; Featherstone and Kazamias 2001; Harmsen 1999; Radaelli 1997, 2000) but the term itself has taken a number of meanings. Indeed, Olsen (2002: 923–4) alone has identified five meanings:

• changes in external boundaries

• the development of institutions at the European level

• the penetration of national systems of governance

• exporting forms of political organisation

• a project of political unification.

For the purposes of this study we are using a rather common conception of this notion which entails two steps: first, the gradual creation of a new institutional framework at the European level which shares power with the Member States (Risse et al. 2001: 3) and second, the consequences of this process for the normative order, the institutional arrangements and the policies of these states.

The first step is a significant one because the representatives of the state are called upon to exercise formal power in an institutional framework whose outputs they can shape – in part – but cannot control. The exercise of legislative initiative is a good example of this problem: it is the European Commission, not the individual Member States, that formally possess the exclusive right to make legislative proposals in, say, the area of the single market. Although individual Member States have the right and the opportunity to – and some actually do – try to influence the content of the proposals of the Commission – as part of a wider competition to ensure that their own policy prevails at the European level (Héritier 1996), there is no guarantee that these efforts will be successful, not least because there is (frequently fierce) competition from other Member States that have different policy traditions and perceptions about optimal policy design.

The process of policy formulation (which includes formal decision-taking) provides another example. As long as the Council of Ministers was the only real legislator at the European level acting on consensus (or even unanimity), individual Member States could at least mitigate the negative implications of radical policy change. The continuous extension of the scope of Qualified Majority Voting (QMV) and, more importantly, the expansion of the formal powers of the European Parliament (especially after 1993) have further diluted the ability of individual Member States to control policy outputs at the European level. This is so not least because decision-making in the European Parliament relies largely but not exclusively on ideology (Hix 2002). Moreover, given that an increasing number of domestic ministries are involved in the management of EU affairs, the need to co-ordinate them becomes a Herculean task (Kassim et al. 2000, 2001).

As regards implementation (Dimitrakopoulos and Richardson 2001), three key elements must be highlighted. First, although formally directives (the main legislative instrument used by the EU) are expected to define the policy objectives and leave the choice of means at the discretion of the Member States, in the run-up to the establishment of the single European market they have become extremely detailed to such an extent that their differences from regulations have almost disappeared. Second, the jurisprudence of the ECJ has further reduced the autonomy of the Member States in that stage of the policy process through the establishment of the doctrines of direct effect and supremacy of EU law and the Francovich jurisprudence (Bleckmann 1997; Craig and de Búrca 1995; Rideau 1994). Third, after 1993 (entry into force of the Treaty ...