1

Globalization, labour force participation and the gender gap

Theresa Devasahayam

Introduction

Asia has undergone rapid economic growth in the past few decades, issuing phrases such as the ‘the East Asian Miracle’, ‘the Asian Era’ and ‘Rising Asia’. East Asia has seen the highest rate of economic growth at 6.1 per cent in comparison to all other regions in the world according to 2009 estimates (International Labour Organization 2010). The burgeoning economy of China has had positive spill-over effects on the countries in the region and thereby has been critical in sustaining relative high levels of economic growth. Although showing much slower growth rates for the same year owing to the economic meltdown, Southeast Asia has long been recognized as a fast developing region in the world, accompanied by impressive economic growth indicators. Strong levels of growth have been attributed to high savings rate, the creation of human capital, market reforms, the role of state intervention, cultural ideologies, namely the Confucian ethic, and the emergence of labour-intensive export manufacturing industries (Kaur 2004).

Since the 1960s, industrialization has made firm headway in East Asia and Southeast Asia. Government intervention has largely been credited with the rapid and sustained economic growth of Japan, South Korea and Singapore. In Southeast Asia, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand thrived in the 1980s and the 1990s as a result of prudent structural changes and selective industrial policy (Jomo and Chen 1997). Government intervention may not have been as significant a factor for economic growth; rather regional economic dynamics and direct foreign investment from the newly industrializing economies of the region have been cited as being far more critical in spurring development.

The impact of globalization driven by cross-border capital movements, rapid technology transfer, and communication and information flows has further heightened the momentum of economic growth in the region. On the international stage, it has been argued that the Asian economies might have gone ‘too far in pursuing globalisation – and too fast’ as the region has ‘slipped into an over-reliance on external, extra-regional demand’ (Lee 2009). Yet globalization has been touted as the major reason for jumps in household incomes and better living standards. In a nutshell, globalization has been instrumental in reducing poverty rates.

According to AT Kearney and Foreign Policy (AT Kearney 2007), Singapore and Hong Kong are the most globalized in economic terms among 72 countries in the world. Although Vietnam, which was included in the list in that year, did not make it to the top twenty, it was ranked tenth in terms of trade, indicating its commitment to trade liberalization. While globalization has been instrumental in the economic development of many countries in Asia, a mixture of positive and negative effects has been felt by different segments of the local populations. It has been argued that the economies of Southeast Asia have primarily been export-oriented and, therefore, have had the vigour to generate employment in the manufacturing sector (Rasiah and Yun 2009). Trade policies have also had an effect on women’s employment and income (Fontana 2009). Export growth, facilitated by trade liberalization, does not mean, however, that the demand for female labour increased at a faster rate than demand for male labour, resulting in an equalization of women’s and men’s wages.

In reality, gender-based discrimination in labour markets has been found to persist in spite of economic liberalization (ibid.). Furthermore, a shift towards more capital- and skills-intensive forms of production and the relocation of jobs from the formal to the informal economy coupled with the removal of tariffs has reduced government revenues which has had a negative impact on women’s employment (United Nations 2009). Thus, the assumption that globalization is effective in improving women’s condition by creating manufacturing employment opportunities has been debunked as evidenced by the fact that gender wage gaps, for example, in the Asian region, have not closed.

Undoubtedly, rapid economic growth coupled with industrialization and globalization processes have provided Asian women with diverse employment opportunities (cf. Dunn and Skaggs 1999). This chapter aims to explore women’s employment situation in Asia and the evidence for gender discrimination in employment by covering a number of related issues. While there have been greater numbers of women becoming active contributors to economic growth across the Asian region, the chapter shows how gender inequality persists because of structural, political, economic and social factors as reflected in the poor employment practices, worsening of labour conditions and lower wages for many women workers around the world as a result of globalization (cf. Prieto-Carrón 2008; Standing 1989, 1999; United Nations 2009). In particular, women have been marginalized in five respects: (1) the formal sector of the economy; (2) the gendered division of labour; (3) the exploitative nature of multinational corporations; (4) the double burden they face in balancing their roles as workers and caregivers in their families; and (5) the negative effects of structural adjustment programmes of the international financial institutions.

This chapter shows the extent to which Asian women are caught in a bind because their engagement in the labour market has mostly been regarded as complementary to the work men do and, thus, their work is accorded secondary economic value (Devasahayam and Yeoh 2007). By filling certain kinds of jobs assigned to them, whether in the countries of their home origin or across the countries in the region, they are unable to mitigate gender inequality and are forced to conceal and, in turn, reinforce, either consciously or unconsciously, the structural, social and cultural constructs that define their role and identity as women.

‘Gainfully employed?’ Asian women’s experiences

The concept of labour force participation is useful because of its value in explaining why certain groups are employed in specific sectors. Specifically women’s labour force participation rate refers to the ratio of their participation in the labour force in comparison to the total population. Labour force participation is generally determined by wage rates, changing attitudes to women taking up wage employment, women’s educational level, delayed marriage, and low birthrates. Global indicators for women’s employment which include status, sector and wage earnings may also be applied to Asian women, with men more likely than women to be employed in formal, salaried work, and with women more likely than men to be employed in flexible forms of labour and earn less for the same type of work.

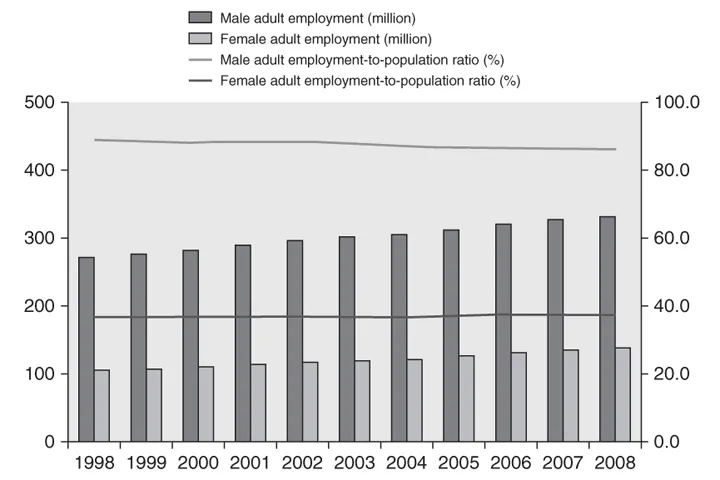

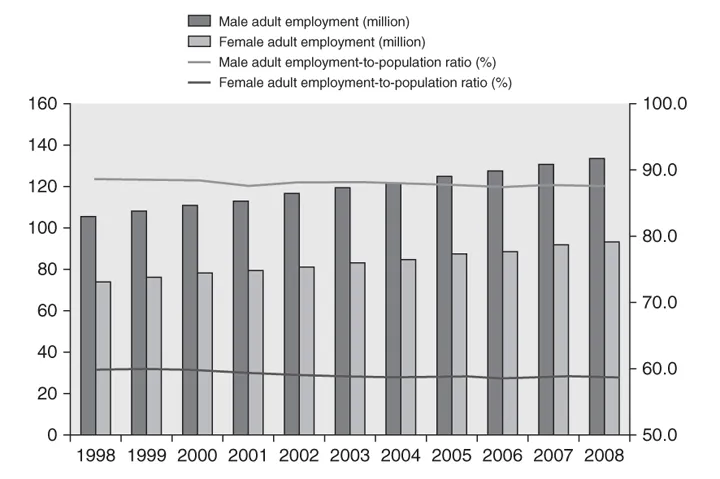

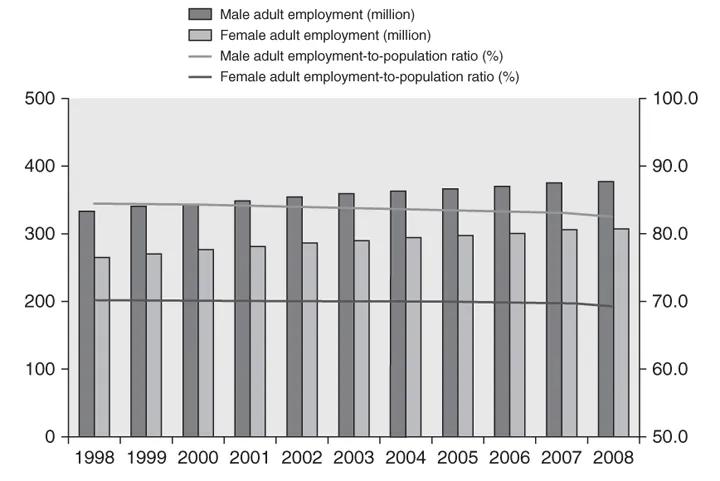

Comparing the three major regions in Asia, namely Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia, South Asia is at one extreme of the spectrum with male economic participation rates more than twice that of female economic participation rates compared with East Asia where the gender gap is not as wide (see Figures 1.1 and 1.3). In both regions, nonetheless, there has been a steady rise in female economic participation in 1998–2008. In contrast, in Southeast Asia, women’s economic participation has been fairly high although not as high as in East Asia; however, women’s lagging rates of employment behind men’s employment was slightly greater in 2008 as compared in 1998 (see Figure 1.2). Interestingly, women’s economic participation levels have been much higher in Southeast Asia compared to South Asia.

East Asia in particular has been said to have a relatively small gender gap in terms of access to jobs as compared to the rest of Asia as well as other regions in the world (International Labour Organization 2009a). As such, the female vulnerable employment rate tends to be much lower there than in many parts of the world where women are often trapped in insecure employment characterized by low productivity and low earnings.

By and large, in the Asian region, female employment outnumbers male employment in some sectors in the developing countries. The export-oriented industries, for example, have been said to be a highly feminized sector. Since the 1980s, the economies of Asian countries have been heavily export-oriented (Radelet et al. 1997; Radelet and Sachs 1997; Sally 2008). This was found to be the case for Taiwan which was increasingly open to trade from the early 1980s to the early 1990s (Berik et al. 2002). These gains, however, have proven to be unsustainable in some economies because of shifts to skills- and capital-intensive forms of production which have favoured men over women (United Nations 2009). For example, in South Korea, employment rates for women declined from 39 to 35 per cent from 1980 to 2004 (Berik 2008). In contrast, the reverse was true of Thailand where there has been a steady rise in labour participation rates over the decades (Jomo 2009).

The persistence of gender

Nonetheless, there has been distinct gender segregation in most job sectors in many Asian countries. Women are over-represented in the electronics, textiles, and apparel sectors while men are found not to dominate any one employment sector (Berik et al. 2002). In fact, the greater the share of exports in the garment, textile and electronics industries, the greater the impact has been on the employment of women (Standing 1999).

It is not uncommon for patriarchal gender norms to have been found to govern hiring, training and labour policies and, as such, women tend to be excluded from higher-paid, skilled jobs compared with men. This was the argument made of South Korea and Taiwan (Cheng and Hsiung 1994; Nam 1994; Seguino 1997). In a survey, 94 per cent of women said that they faced greater obstacles securing full-time employment compared with men (Kang and Rowley 2005). Their conclusion is justifiable since 46 per cent of women are temporary workers, while only 15.2 per cent of women hold administrative and professional positions and 7 per cent are managers.

Taiwanese women, in contrast, have been found to fare better than their South Korean sisters. A study on female managers found that women of the current generation were more optimistic about securing promotions than the previous generation (Chou et al. 2005). In fact, women represent 19 per cent of managerial positions in Taiwan; this is a promising trend since women make up 41 per cent of the total workforce, reinforcing the idea that men make good managers while women play supportive roles even in the workplace.

With globalization, traditional gender ideologies have persisted. Describing the work carried out by men and women workers in the Fujitsu Electronics plant near Kagoshima, Custers (1997: 332) says:

Traditional gender ideologies continue at the transnational level. Migration has seen women take on jobs in the caregiving sector as nurses, caregivers and domestic workers in the more affluent labour-receiving countries faced with the care crisis (Beneria 2008; Ehrenreich and Hochschild 2003), a topic that will be taken up at greater length in Chapter 3. These jobs are considered to be typically female and are associated with the private sphere and, as such, there is the uncertainty around whether or not they constitute ‘real’ work (Oakley 1974). The act of feminizing these jobs has rendered them low paid, peripheral, insecure and less valued (United Nations 2004). The women who take on these jobs also risk not having social protection.

Where are the gender gaps?

It was once assumed that the gender gaps in the developed countries were not as wide as they were in the developing countries. A World Bank report of 1999 states:

But this assumption has been contested (Khondker 2009). Ironically, countries with very high human development outcomes have shown lags in closing the gender gap (see Table 1.1). The impressive record of the Philippines makes this point. The Philippines, although it has a much lower overall human development profile, has done remarkably well in bridging the gender gap and has been placed in the top ten countries in the world, ahead of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and the United States (World Economic Forum 2009). Compared with Singa...