eBook - ePub

Reflections on the Cliometrics Revolution

Conversations with Economic Historians

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflections on the Cliometrics Revolution

Conversations with Economic Historians

About this book

This volume marks fifty years of an innovative approach to writing economic history often called "The Cliometrics Revolution." The book presents memoirs of personal development, intellectual lives and influences, new lines of historical research, long-standing debates, a growing international scholarly community, and the contingencies that guide an

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I: BEFORE THE NEW ECONOMIC HISTORY: North America

Moses Abramovitz

M. C. Urquhart

Anna J. Schwartz

Walt W. Rostow

Stanley Lebergott

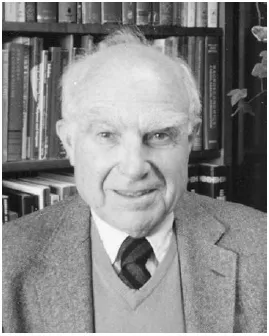

MOSES ABRAMOVITZ

Interviewed by Alexander J. Field

Moses Abramovitz was William Robertson Coe Professor of American Economic History, Emeritus, at Stanford University, Stanford, California. He was born in New York City in 1912 and died in Stanford in 2000. He was educated at Harvard College (B.A., 1932) and Columbia University (Ph.D., 1939), and began his long association with the National Bureau of Economic Research in 1938. During World War II he served at the War Production Board and at the Office of Strategic Services. After two more years at the NBER, he was professor of American Economic History at Stanford University from 1948 until his retirement in 1977. Abramovitz was elected Fellow of The American Statistical Association and Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, both in 1960, was named Distinguished Fellow of the American Economic Association in 1976, and was elected Foreign Member of the Academia Nazionale dei Lincei (Roma) in 1991. He was President of the American Economic Association (1980), of the Western Economic Association (1989), and of the Economic History Association (1992). From 1981 through 1985 he was Managing Editor of The Journal of Economic Literature and continued as its Associate Editor through 1993. He was honored with a Festschrift edited by Paul David and Melvin Reder, Nations and Households in Economic Growth (Academic Press, 1974). He completed Days Gone By: A Memoir for my Family (2001) only a few months before his death. ALEXANDER J. FIELD, of Santa Clara University, conducted the interview at the offices of the JEL at Stanford on December 9th and 16th, 1992. Field writes:

Moses Abramovitz was one of a select group of scholars whose path-breaking empirical work has vastly expanded our understanding of the dimensions and determinants of economic growth and fluctuations in the industrializing and industrialized countries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He is best known for his work on inventories, which identified the critical role of fluctuations in inventory investment in short-term cycles in output, for his studies of long swings of growth in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for his work separating the relative contributions of technical change and capital accumulation to economic growth in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and for his research on catch-up and convergence: the closing of the productivity gap between the United States and its competitors in Western Europe and Japan.

How did you first get interested in economics?

It was during my first year at Harvard, I intended to concentrate in history and literature. Two courses that I took during my first year, however, proved to be quite uninteresting. In English literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the professor talked only about the authors’ styles and those of the earlier writers from whom they derived; the substance of the literature, what was being said, was of little or no concern. And the course in history was the great survey course, which all the undergraduates at that time took. I thought it fairly shallow. But I took a very good beginning course in economics, and I had a very good instructor. His reading list offered us the opportunity to read a short book by H. D. Henderson in the old Cambridge Economic Handbook Series called simply Supply and Demand (Harcourt, Brace 1922). That proved to be a formative, almost aesthetic, experience. It provided in utterly lucid terms a summary of the neoclassical theory of that time. It showed you how from people’s tastes, the state of technology, and people’s feelings about the relative costs of different kinds of jobs one could derive the prices of finished goods, the relative quantities of output of different kinds of goods, and factor prices, and the whole thing hung together. It seemed a lovely structure. It fascinated me and I could see its practical applications, so I decided to concentrate in economics. This was in my freshman year. When I came back in the fall for my sophomore year, I was assigned a tutor, Edward S. Mason, then a young assistant professor. When I paid him my first visit in the witching month of September 1929, I asked him, “Well, Professor, when is the stock market going to break?” He answered without hesitation, “Almost immediately.” When I came back for my second meeting two weeks later it had happened. And then I learned something about economists. I said, “Well, Professor, you must have made a mint of money.” He laughed, “Are you crazy? I’ve never owned a share of stock in my life.”

I had another very good tutor later on, Douglas Vincent Brown, the man who later taught labor economics at MIT for many years. And there was a talented group of economics students in Dunster House where I lived. We saw each other often and talked at great length; all of us became economics professors or writers. Paul Sweezy was there, Spencer Pollard, John Perry Miller and still others. We were a self-reinforcing support group.

Besides Professor Mason and Professor Brown, were there others at Harvard who particularly impressed you as an undergraduate?

Frank Taussig was surely one. He taught price theory to both undergraduates and graduates. I took both courses, and I owe my knowledge of the classical writers and even more of Alfred Marshall to him. But the man who impressed me the most as an undergraduate was Schumpeter, who was a visiting professor in 1931. I came to know Schumpeter much better later when I returned to Harvard in 1936.

How did the graduate training you received at Columbia compare with what you received at Harvard?

If I hadn’t been to Harvard, Columbia would have been a poor preparation. But I had a good preparation at Harvard. I have mentioned Taussig’s courses. This was important because Columbia, at the time, offered no course in price theory for graduate students. It was regarded by the faculty as theology, and they refused to teach it. The result was that graduate students, who knew better, organized themselves into study groups that were led by Milton Friedman and me because we were among the few students with some prior theoretical training. The neglect of price theory went on at Columbia for years.

Was this antipathy to micro theory due to Columbia’s greater concern for aggregative, more macro aspects of the economy?

Yes. Also, there was Columbia’s institutional flavor. As between Harvard, Chicago and Columbia, which were the leading schools at the time, Columbia was the one with an institutional flavor and an empirical bent.

Whom did you work with ultimately?

I worked with J. M. Clark mostly, so far as anybody could work with that brilliant but reclusive man. He rarely answered a question orally. Instead, he went away to think it over and responded by letter. Perhaps that was better.

Before we go further, I wanted to ask you about your government service during the war as an economist for the War Production Board and the OSS, and later as an advisor to the US delegation to the Allied Commission on Reparations. Were there ways that government service enriched your understanding of economics or suggested certain problems?

I’m not sure whether it was government service in itself or simply the subjects with which I was concerned during the war, which later became important for me. At the War Production Board I was an assistant to Simon Kuznets. We were attempting to put together estimates of the production capabilities of the US economy as a basis for major decisions about such matters as the size of the armaments program that was feasible, given the requirements for civilian consumption. We made estimates of potential GNP at full employment for past years and tried to extend them, having regard to the growth of the labor force, the numbers of men who were being pulled out to serve in the armed forces, the number of women coming into the labor force to replace them, and the amount of capital accumulation, adding an allowance, as well as we could, for the growth of productivity. We were, in effect, formulating a forward-looking picture of what our aggregate economic capabilities might be and what that implied for the armaments production program and for the allocation of resources between the armed forces and civilian production.

There were two great controversies to which all this applied. The first one, however, was largely resolved by the time I came to Washington in early 1942. That had to do with the country’s production capabilities when our first great armaments program was being planned in 1940 and 1941. When the early plans were being put together, the only clear evidence of the country’s capacity to produce went back to 1929 because the intervening years were those of the Great Depression. Absurd estimates were proposed that put our production capacity at perhaps ten percent more than we had done in 1929. But the group around Kuznets and, in particular, Robert Nathan, became convinced that our economic capabilities were vastly greater, making allowance for the growth in the labor force and for the increase in productivity and, of course, for the recovery in the intensity of use of the resources we had. Well, Nathan and a few others like Richard Gilbert managed to sell the view that we could have a huge armaments production program, and I think that may have been the most important strategic decision made in Washington during the war. When the contracts for numbers of airplanes, larger than anybody had ever conceived of before, were awarded, and similarly for tanks and for ships and so on, it turned out that we did have the capacity to produce them along with a flow of civilian goods which was at least as plentiful as anybody had expected. And, in the end, the Axis was overwhelmed by Allied men and materiel. When this production success became apparent, however, the ambition of the military knew no bounds, and they formulated armaments programs which, in the opinion of our group at the War Production Board, could never be handled. If contracts on that scale had been awarded, competition among producers for the limited supplies of labor and crude materials would have caused great misal-locations of resources. That was the second fight about war production. It was a very difficult one indeed because the Army strongly resisted having to cut their programs. But we were largely successful.

But to answer your question, in what way was this experience formative? After a year at the War Production Board I was drafted into the Army and assigned to the OSS (Office of Strategic Services). There I was put in charge of the section on German industrial intelligence. The problem here was the same: What were Germany’s economic capabilities; what was bombing doing to Germany’s economic capabilities? So I worked on Germany for a couple of years, and that is how I came to work with the Reparations Commission. These experiences did more than make me appreciate the importance of GNP for the outcome of the war, a war that was won by GNP. The question that lingered in my mind was this: How did the different countries – the United States, France, Germany, Britain, Japan, the USSR – come to have the economic capabilities which, in fact, they did have? In short, I was thinking about economic development. That was the formative influence of my wartime experience.

But your dissertation was on inventories?

Why, no. My dissertation was a theoretical essay. It was called “Price Theory for a Changing Economy.” The question that I posed was: If supply curves and demand curves are in process of change, what effect does this have on the allocation of resources and on the way prices are set? Obviously, the old static theory had a kind of answer to this question, but I was asking whether there was something more. And it was in the course of answering that question that I came to consider inventories as one of the ways in which the economy responded to prospects of change. So I suppose it was in part because of that that I was eventually recruited by Mitchell to come to the Bureau to work on inventory cycles.

The thesis itself was largely theoretical.

It was completely theoretical. My Harvard training had, after all, made a lasting impression.

So it was only after you joined the Bureau that you began to do empirical work?

That’s right, only after I joined the Bureau in 1938. I worked there for four years before I went to Washington. You should know, first, about the state of business cycles research at the Bureau. When the Bureau started in 1920, their first project was national income. That produced Wilford I. King’s book. The second project was business cycles. That was Mitchell’s undertaking to extend the work – limited work, as he saw it – that he had been able to report in his classic 1913 volume. His conception of the project was that he should repeat what he had done for the 1913 volume, only in a more elaborate form, with some more extensive data, covering a longer time period. Mitchell’s 1927 book, Business Cycles: The Problem and its Setting, was an elaboration of Part I of the 1913 volume. Then he went on to study the cycles in production, prices, construction, marketing, inventories, credit and banking, the money supply, and so on. Working essentially single-handedly at first, later with much help from Kuznets and later still with much help from Arthur Burns, he had completed almost the entire cycle of these studies. It was a remarkable achievement. But when Mitchell and Burns came to review these chapters, they decided they were not adequate. They would have to be redone, and it was hopeless to think that Mitchell could do the job by himself. So they decided to enlarge the staff by adding research associates to each of whom one of these chapters could be assigned. These associates would do still more extensive empirical work and perhaps contribute a deeper understanding. Finally, Mitchell and Burns would put the whole thing together. That was the state of affairs when I came in. There was a “chapter” on production of 850 pages. There was a “chapter” on prices of 450 pages. There was a “chapter” on construction of 350 pages. I was given a short chapter on inventories; it was only 60 pages long.

Who else was on the research staff at the Bureau at the time?

Well, if you are talking about the major members, there were, of course, Mitchell, Kuznets, and Burns. Leo Wolman worked on unions, wages and labor markets. Fred Mills was working on prices. There was Fred Macaulay, who studied the securities markets and who published that very good book on stock prices, bond yields, and interest rates. Sol Fabricant was doing his path-breaking work on production and productivity. Milton Friedman was there for a while working with Kuznets on incomes from professional practice. He largely took over that work from Kuznets and made it his own. Alan Wallis, Geoff Moore, Ruth Mack and Thor Hultgren were other younger people in the business cycles program. So we were a goodly group.

The genesis of your book on inventories was essentially an assignment to complete work that Mitchell had started . . .

Yes. But you should know that the Bureau’s collection of data on inventories was quite small, and it referred to the most diverse and often insignificant commodities. That is what Mitchell’s chapter was based upon. The collection was in itself altogether inadequate to provide any useful picture of aggregate inventories and inventory investment. Fortunately, Kuznets was then completing his book on national product from the expenditure side (1946). In that connection, he had made crude estimates of aggregate inventory investment that were one component of total investment and product.

So I spent some months finding out how he had arrived at his numbers. He had a wonderful set of workbooks. You could trace every figure. I went through his work sheets carefully, asking him lots of questions, and that’s how I really became acquainted with Simon. His inventory figures were another example of Kuznets’ ability to use the most imperfect kinds of materials and proxies to make valuable estimates. His judgment about the construction and use of these materials was so good that the results turned out in the end to be quite consistent with the measures that the Department of Commerce later made on the basis of surveys of manufacturing, wholesaling, retailing and other sectors. Kuznets’ data yielded very striking results. They suggested that some 85 percent of the change in aggregate output from the peaks to the troughs of short recessions consisted of changes in the volume of inventory investment, and similarly, but not quite so strikingly, in the longer expansion phases of business cycles. So in the minor fluctuations, which were the larger part of the cycles identified in the Bureau’s chronology of business cycles, it was not investment in durable equipment or structures that was the major proximate source of the fluctuations in output, it was fluctuations in the rate of inventory investment. This finding was the most important thing reported in the book. It was a result yielded by Kuznets’ estimates and, indeed, one he had anticipated in an earlier paper. Then I used Mitchell’s miscellaneous collection of time series to formulate views about the very different behavior of finished goods, goods in process, and purchased materials inventories.

What notable advances have occurred in our understanding of inventory behavior since you wrote?

There have been very important advances. The theoretical model, which relates inventory investment to business cycles, was given an enormous push forward by Lloyd Metzler and Ragnar Nurkse. Before they wrote, J. M. Clark and Kuznets had proposed speculative hypotheses about inventory investment based on the acceleration principle. But in their models, the movements of sales were taken as given and inventory investment was a response. I got no further in my book. Metzler and Nurkse worked out models in which income and sales responded to inventory investment and vice versa, and they showed how cycles of output could be generated from this interaction. That was one great forward movement.

Beyond that, there have been very considerable advances in our notions about what constitutes rational inventory policy and, therefore, what expectations we can hold about the way inventories would behave during cyclical fluctuations. So really a great deal has been done since my book.

It seems that after the war your inte...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- ROUTLEDGE EXPLORATIONS IN ECONOMIC HISTORY

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION: ECONOMIC HISTORY AND CLIOMETRICS

- PART I: BEFORE THE NEW ECONOMIC HISTORY: NORTH AMERICA

- PART II: BEFORE THE NEW ECONOMIC HISTORY GREAT BRITAIN

- PART III: NEW ECONOMIC HISTORIANS: THE ELDERS

- PART IV: LA LOI LAFAYETTE: CLIOMETRICS AT PURDUE

- PART V: THE EXPATRIATES

- PART VI: FROM THE WORKSHOP OF SIMON KUZNETS, ECONOMIST

- PART VII: FROM THE WORKSHOP OF ALEXANDER GERSCHENKRON, ECONOMIC HISTORIAN

- AFTERWORD: THE SHOCK, ACHIEVEMENTS AND DISAPPOINTMENTS OF THE NEW

- ABBREVIATIONS

- REFERENCES

- CREDITS

- CONTRIBUTORS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reflections on the Cliometrics Revolution by John S. Lyons,Louis P. Cain,Samuel H. Williamson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.