![]()

1The ubiquity, importance, and uniqueness of national accounting

John Maynard Keynes famously foresaw “a new era of ‘Joy through Statistics’” as his contemporaries began moving beyond theoretical economics and getting involved in applied empirical work (Moggridge, 1976, quoted in Stone, 1978). Looking back from the second decade of the twenty-first century, it appears that Keynes was spectacularly right. Statistics are ubiquitous in many areas of modern life, including political and opinion polls, sports statistics, demographic trends, and, perhaps more than any other type, economic data.

The growth rate of gross domestic product, the level and changes of the rate of unemployment, the inflation rate (as measured by changes in the Consumer Price Index – CPI), and other key macroeconomic figures appear daily in the media. They have the potential to shake markets, affect government policies and corporate strategies, and – increasingly – determine election results. Ratios using GDP in their denominator are used in international agreements, multilateral treaties, and various conditionalities. The Annex to the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 – which created the European Union (EU) as well as its single currency, the Euro – stipulated maxima of 60 percent for the debt-to-GDP ratio and 3 percent for the deficit-to-GDP ratio as admission criteria. Public debt as a percentage of GDP is also a frequently used criterion for the imposition of austerity measures on countries, either by external lenders (such as the EU or the International Monetary Fund – IMF) or internally by government edict (Poland’s Public Finance Act, for example, triggers an automatic freezing of the country’s proportion of deficit to budget revenues when the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 50 percent).

Nor is this concern with economic headline numbers restricted to policy circles. The recent academic controversy surrounding a 2010 paper by Reinhart and Rogoff is a case in point. The paper argued that gross public debt in excess of 90 percent of GDP was associated with “notably lower rates of growth” (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010). This idea was criticized in a 2013 paper by Herndon et al. and fueled a furious debate in the op-ed section of The New York Times. While some of the controversy had to do with calculation errors in the dataset used as the basis for the 2010 paper, the larger question emerging from this involves the centrality of headline macroeconomic data as a basis for supporting economic policies, both nationally and internationally. Paul Krugman made this point succinctly in the same newspaper: “Austerity enthusiasts trumpeted that supposed 90 percent tipping point as a proven fact and a reason to slash government spending even in the face of mass unemployment” (Krugman, 2013). This certainly casts doubt on the familiar notion of evidence-based policy. But coding errors aside, how objective or neutral is the evidence to start with?

The frequent and high-profile attention and emphasis given to GDP and other national accounting figures have stimulated growing interest in the way such “data” are calculated (the inverted commas betray one of the key points made in this book, i.e. that national accounts aggregates are not given by simple measurement or statistical sampling, as the Latin origin of the word – datum – would imply, but are rather constructed in a complex manner). Unlike other macroeconomic statistics such as the unemployment rate, the national accounts are intricate systems, combining hundreds of data items from multiple sources, and using a variety of assumptions, extrapolations, and imputations to arrive at the headline numbers.

This makes national accounting unique. In a way, the art of national accounting is more akin to that of economic modeling than to the far more straightforward statistical processes involved in calculating other macroeconomic indicators. A simple example would suffice to illustrate this contrast. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) defines the unemployed as those who “do not have a job, have actively looked for work in the prior 4 weeks, and are currently available for work” (BLS website). The entire methodology, including a description of data sources and several examples for calculating the unemployment rate, is covered in nine pages. By contrast, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) does not even attempt a short definition of GDP or national accounts on its website, instead providing a separate section for “Methodologies.” In addition to several primers and introductory papers on the subject, the main document in this methodological section – Concepts and Methods of the U.S. National Income and Product Accounts – is 318 pages long (not including Chapters 11 and 12, which are listed separately). The equivalent current international standard, the System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA 2008), is more than twice as thick with 722 pages. SNA 1993 was even bigger, at 838 pages, compared with 253 and 57 pages for SNA 1968 and SNA 1953, respectively (a trend constituting a methodological inflation of sorts over the past half a century).

Thus it becomes clear that national accounts are not regular economic statistics by any means, if they can be considered statistics at all. In fact, national accounting uses statistics from various sources as inputs, which, through a combination of identities, accounting rules, pieces of economic theory, and assumptions (as well as increasingly more imputations where certain variables cannot be measured directly), are transformed to arrive at the final estimates. A recent paper by the top national accountants in the US describes part of this statistical alchemy:

In the United States, the GDP and the national accounts estimates are fundamentally based on detailed economic census data and other information that is available only once every five years. The challenge lies in developing a framework and methods that take these economic census data and combine them using a mosaic of monthly, quarterly, and annual economic indicators to produce quarterly and annual GDP estimates. For example, one problem is that the other economic indicators that are used to extrapolate GDP in between the five-year economic census data – such as retail sales, housing starts, and manufacturers’ shipments of capital goods – are often collected for purposes other than estimating GDP and may embody definitions that differ from those used in the national accounts. Another problem is some data are simply not available for the earlier estimates. For the initial monthly estimates of quarterly GDP, data on about 25 percent of GDP – especially in the service sector – are not available, and so these sectors of the economy are estimated based on past trends and whatever related data are available. For example, estimates of consumer spending for electricity and gas are extrapolated using past heating and cooling degree data and the actual temperatures, while spending for medical care, education, and welfare services are extrapolated using employment, hours, and earnings data for these sectors from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

(Landefeld et al., 2008)

In addition to extrapolations due to data availability problems, many crucial decisions need to be made regarding what should or should not be included in GDP. Financial services, for example, used to be excluded based on the convention that interest payments (financial firms’ main input and output) were merely transfers, but this changed in recent decades as financial intermediation crossed the production boundary and became defined as a productive activity. Even for items that are included in GDP there are some implicit transactions that are imputed. While the market value of fee-based financial services can be readily measured, the value added of those not provided for a fee cannot, and is imputed on the basis of interest differentials between loans and deposits. Another example is the value added of owner-occupied dwellings, imputed based on the rent that their owner would have to pay otherwise.

All of these processes require a lot of ingenuity, but also leave plenty of room for maneuver, a fact that is evident throughout the history of national accounting estimates around the world and over the centuries. One current example of this flexibility is the recent revision in the BEA methodology for the second-quarter estimates of US GDP in 2013. The new definition includes research and development as well as original entertainment works as part of fixed investment – items that formerly were excluded since they were considered to be intermediate inputs in the production process (and also due to conceptual difficulties with their ownership and durability). This adjustment has added $560 billion to total output (more than the entire GDP of Sweden), and has increased the US’s GDP to $16.2 trillion, conveniently “reinforcing America’s status as the world’s largest economy and opening up a bit more breathing space over fast-closing China” (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2013). Nor is the US the only country to make this change. Canada had done the same in 2012 and Australia as early as 2009, at the time “leapfrogging Canada in the OECD’s country rankings of GDP per person” (The Economist, 2013, 64). This economic race echoes the concerns of seventeenth-century national accounts pioneers such as William Petty and Gregory King with inter-country comparisons of economic strength and position. As we shall see below, this is not a coincidence.

Given both the importance and complexity of constructing as well as adjusting the content and scope of national accounts, it becomes critical to ask: what drives the evolution of these intricate systems in different periods and countries, and what explains the differences (and, later, revisions) between the various resulting structures? That is the main research question of the next two chapters of this book. Received histories of national accounts take a technocratic approach to the topic, explaining the development of these estimates as a statistical exercise informed by economic theory and available data. The next chapter proposes an alternative hypothesis – power drives measurement – which views national income estimates as exercises in numerical rhetoric. A key force in shaping national accounting has been national economic policy, not merely as a general, passive end-use of national accounts but as an influence shaping the structure, content, and revision of different systems to support particular policies advocated by their authors, whether individual or institutional. This was as true in 2014 as it was in the seventeenth century.

![]()

2National accounting as a historically and politically contingent art

It is just as foolish to fancy that any philosophy can transcend its present world, as that an individual could leap out of his time or jump over Rhodes.

(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Preface to The Philosophy of Right, 1821)

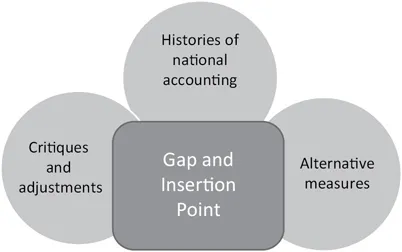

One part of the literature on national accounting consists of histories, either in one country or globally, written in a mostly descriptive style. Another literature strand consists of political economy critiques of (current) national accounting standards, based on their inclusion or exclusion of certain categories of economic activities. The problem with these two sub-literatures is that while the first is historical but not critical (assuming overall progress and improvement through time), the second is critical but a-historical, touching only briefly (if at all) on previous systems and thus not investigating how the issues it critiques came about in the first place. Figure 2.1 visualizes this problem.1

2.1Technocratic histories of national income estimates

Works in the historical literature on national accounts provide plenty of historical and technical detail, but seem to assume overall progress (albeit occasionally interrupted) in the development of national accounting systems. Such histories of national income estimates and accounting impose a twentieth-century utilitarian view – that the accounts are based on economic theory and attempt to measure output and productivity – on a 400-year-old tradition which they do not fully understand.

The classic work in this strand of literature is Studenski’s The Income of Nations (1958). Although treating concepts and methodology as well as presenting contemporary accounts for a selected group of countries, the book contains (and is most cited for) a detailed history of estimates of national income from the mid-seventeenth century to the 1950s, comprising its first ten chapters. Studenski concludes this historical part of the book with a section entitled “Forces that influenced the development of the past three hundred years” (158–160). Of the eleven factors listed, the top three are individual scholars’ initiative and interest, advances in economic theory, and external events such as severe economic crises, wars, and revolutions.

While this is certainly a reasonable list of factors, all of which may have contributed at some level to motivating the development of national accounting, there is no clear thread connecting these seemingly isolated forces, other than a general emphasis on these factors as the most important in the overall history of national accounting. As we will see, even this emphasis is misguided, since individual initiative and economic theory both flourished in periods and places where no significant or original efforts to estimate national income were observed, while wars, revolutions, and severe economic crises – viewed in isolation – are too frequent and ubiquitous (particularly in European history) to serve as an explanatory factor of any power.

Another work in the historical strand of the national accounting literature is John Kendrick’s article in the journal History of Political Economy (Kendrick, 1970). By the author’s own admission, the first part of the piece draws heavily on Studenski. Kendrick divides the history of the development of national income accounts into two main phases. The longest period, up to World War I, is characterized by him as dominated by individual estimates driven primarily by intellectual curiosity coupled with ‘nationalism’ – “the desire to compare the economic performances of rival nations and the need to build quantitative bases for analysis of the effects of proposed tax policies and other policies meant to strengthen and reform national economies” (284).

The second phase in Kendrick’s history begins in the 1920s, with progress accelerating due to the heightened need of national governments for better quantitative evidence in the wake of the Great Depression, World War II, and the Cold War. Other motivating factors mentioned are the needs of reconstruction and economic development, theories of demand and employment, and new theories of economic growth. All this resulted in “[t]he invention of the structure of interlocking sets of sector accounts, and the independent formulation of input–output and flow-of-funds accounts, and sector balance sheets capable of integration with the basic production accounts” (ibid., 285). The main idea in this history is that “economic accounts are a continually evolving structure and body of statistics,” with changes and improvements – both past and future – reflecting “interacting dynamic changes in society and the economy, in concepts and economic theories, in data collection and processing, and in methodologies of estimation and analysis” (ibid., 315). Kendrick thus reflects the technocratic view of the development of national accounting in this literature – a secular progress over time, mirroring the progress of economic theory as well as of statistical methods, with each subsequent version superseding, rather than merely replacing, all others.

Kendrick’s student at George Washington University, Carol Carson, wrote her PhD dissertation on the history of national accounts in the US under his guidance in 1971. The thesis served as the basis for her paper “The history of the United States national income and product accounts: the development of an analytical tool” (Carson, 1975). As its title suggests, the paper focuses on the US, and begins by briefly reviewing the early history of national income estimates there. It then discusses the estimates made by the Department of Commerce in response to the Great Depression, the use of national accounts during World War II, and the postwar consolidation of the national income and product accounts. While providing plenty of detail on the economists and agencies involved, as well as the technical evolution of the accounts, the assumption in this paper is similar to that of Kendrick – an ongoing refinement of a tool for macroeconomic analysis.

A similar description of the development of national accounts, in this case for Britain (though only for the period 1895–1941), is provided in Tily (2009). The paper’s main goals as stated by its author are to clarify John Maynard Keynes’s role in the development of national accounts, as well as to showcase the contribution of lesser-known figures of the time, such as Alfred Flux, Arthur Bowley, Josiah Stamp, and Colin Clark. Tily challenges the common wisdom that it was Keynes and his theories that provided the first impetus to the development of national accounting in 1930s Britain, arguing that earlier developments – such as Alfred Marshall’s elaboration of national income concepts, as well as the 1907 Census of Production – were among the original drivers o...