1

INTRODUCTION

The [9/11] attacks showed that, for all its accomplishments, globalisation makes an awful form of violence accessible to hopeless fanatics.1

(Stanley Hoffmann, 2002)

When two passenger planes crashed into the World Trade Center and another flew into the Pentagon building in Washington on 11 September, 2001 the word ‘globalisation’ quickly became a buzzword in nearly every expert commentary on the background for the attacks. While globalisation had long been touted as mostly a force for good, at least for the Western world, the horrifying onslaught of death and destruction in the world’s greatest metropolis of power and capital highlighted the ‘dark side of globalisation’. Analysts warned about a rapidly changing world coming apart, unhinged by sinister forces not properly understood or anticipated. In the shadow of a remarkably long period of economic growth and the spread of the market democracies in the post-Cold War world, religious fanaticism had returned with a vengeance, shattering the Western sense of tranquillity and insulation from the ills and maladies affecting distant zones of conflict. The new evil was said to be feeding itself on abject poverty, glaring inequalities, remnants of Western colonial domination and a visceral hatred of the West’s wealth and success. It thrived in a growing number of Third World failed states, from where it could attack a Western metropolis, the traditional barriers of distance and geography had fallen thanks to the revolution in communication and transportation. These factors, it was argued, provided the ideological and material basis for a new professional warrior class of determined martyrdom-seeking terrorists, seeking to dethrone the world’s remaining superpower, punishing it for its political arrogance, its hypocritical foreign policy and its infidel values of individual freedom and liberal democracy. To many observers, the 9/11 attacks were the culmination of previously observed trends where terrorism was becoming increasingly more irrational in its logic, fanatical in its ideological manifestation, global in its reach, and mass-casualty-causing in its modus operandi. Nearly all previously held assumptions about terrorism as a political phenomenon were dismissed as anachronistic and outdated, and all but the most alarmist and hawkish predictions about terrorism were considered naïve and irrelevant.

There has been a flood of research on terrorism after 9/11. For obvious reasons, terrorism studies have become distinctly more actor-focused. Understanding the rise of al-Qaida, the resilience of its organisation and its support networks and the variety of local affiliate groups and predicting al-Qaida’s next step have been on everyone’s mind. The impact of globalisation on terrorism has become an important topic in the post-9/11 writings on terrorism.2 A common theme is that the new terrorism is a manifestation of resistance to globalisation and the global spread (or imposition) of values of Western market democracies, a kind of reactionary backlash against modernisation. 3 Others argue that since the world is globalising, so is terrorism. Hence, one is witnessing a globalisation of terrorism since patterns of terrorism reflect overall societal changes. The tendency towards loosely organised terrorist ‘networks’ rather than hierarchical organisations, the multinational characters of the new terrorist organisations and their global reach are characteristics which have obvious parallels to how the globalisation process has affected the business economy, national and identity politics, as well as sociocultural trends.4 The growing lethality of terrorism may, for example, be linked to one aspect of globalisation, namely the growing vulnerability of globalising societies to terrorist attacks. During the era of globalisation terrorist groups have gained access to new means, making them more lethal and more global in reach. A related theme is the enormous political impact of terrorism in the age of globalisation. The new-found destructive capabilities of terrorist networks have empowered them and elevated them to being significant actors in international politics and the international economy. Hence, they may also have the power to change the very course of globalisation.5

Beyond various public debates, academic studies of globalisation’s impact on terrorism have until recently excelled in their near-absence, especially in terms of the overall future impact of globalisation.6 Even if there is broad agreement that globalisation is perhaps the single most important process shaping our future, there have been few scholarly contributions in the terrorism literature that aim at capturing long-term shifts caused by the globalisation process.7 After all, nothing is more risky than prophesising in the midst of rapidly unfolding ‘wars’, be they in Afghanistan, Iraq or the global ‘war on terror’. Even though ‘the future of terrorism’ has been a favourite title for books on terrorism for a very longtime, the terrorism-research literature has traditionally drawn surprisingly little from the large body of futuristic studies. Also, general social-science research has also been somewhat ignored, despite the potentially important contributions of conflict theory and quantitative peace research studies to our understanding of terrorism.

Since the mid-1990s, literature on terrorism trends address the future of terrorism under labels like the ‘new terrorism’ ‘the new face of terrorism’ and ‘new generation of terrorists’, but without linking these predictions to processes of long-term societal changes.8 These studies mostly foresee increasingly more lethal forms of terrorism, (which turned out to be true), but argued that the increased lethality would be caused by non-conventional terrorism or weapons of mass destruction (WMD)-terrorism, (which so far has not proven to be correct). This literature drew its conclusions primarily from a few trend-setting events in the mid-1990s such as the first WTCbombing, the Sarin gas attacks by the Aum Shinrikyo sect and the Oklahoma bombing, as well as an apparent predominance of religiously motivated (mostly Islamist) terrorist groups in transnational terrorism. Without pondering the enormous destructive potential of conventional terrorism, forecasts and prognoses focused almost exclusively on WMD-terrorism.9

Towards a framework for predicting future patterns of terrorism

Since its inception in the 1970s, the voluminous literature on modern terrorism contains numerous attempts to predict the future of terrorism. Most of these attempts are unsystematic, however and lack a theoretical foundation.10 The future of terrorism literature has generally suffered from the lack of systematic thinking about how changing societal conditions can produce a variety of both permissive and inhibiting environments for terrorism, resulting in constantly evolving patterns of terrorism. It is often based on observation of related events and extrapolations from single cases, while the evolving contextual or underlying factors shaping the very environments in which terrorism thrives or declines are not properly analysed or understood. Or it tends to focus merely on insufficiently substantiated ‘conditions’, which allegedly have an aggravating effect on the occurrence of terrorism while the countervailing forces are ignored. Consider the following example:

Nearly all conditions thought to breed terrorism will probably aggravate in the short and medium future. Value nihilism; the search for new beliefs, especially by the young generation; disappointment with the established order; and broad public malaise will probably increase. Scarcities, unemployment, ethnic tensions, nuclear angst, acute ecological problems, and the frustration of welfare aspirations are sure to increase in most democracies. Value cleavages and intense disconsensus [. . .] may well grow. International anarchism, hostilities, and fanaticism will expand. Poor Third World countries, well equipped with weapons, but unable to handle their problems, will probably direct their hostility at democracies. The confrontation between communism and democracy will continue and perhaps escalate. Technical tools for expanding terrorism and the vulnerability of democracies to terrorism will increase. [. . .] At the same time basic democratic freedoms will provide a convenient space for terrorism to operate in. Aging population, additional leisure-time facilities, and continued urbanisation will provide ‘soft’ human targets. Modern energy facilities, data networks, roboted factories, and the like will add critical material targets. The ease of international communications and movements, mass-media attention to terrorism and informal networks that support terrorism constitute further trends that will permit or encourage terrorism.11

Needless to say, the author is obviously wrong in assuming that almost every societal process of change will lead to more terrorism. The author identifies a wide range of societal trends that may well have an impact on terrorism, but without any basis in the research literature on the causes of terrorism and without any systematic analysis of variables that ‘breed terrorism’, it is clear that the outcome of such exercises has limited value only. Therefore, one needs a far more stringent methodological approach if the results are to be anything other than mere speculations.

A method that it is widely used in the literature as well as among practitioners is to extrapolate from current trend patterns, assuming that the future will be more of the same and that emerging trends can be spotted by monitoring closely various indicators.12 Although indispensable for short-term predictions, such research strategies need to be complemented by alternative methods. Extrapolation of current terrorism trends remains inevitably an uncertain method of long-term predictions. The risk is that long-term shifts are only understood after they have occurred. Or a temporary short-lived surge in certain forms of terrorism may be erroneously interpreted as a long-term change.

While being primarily a set of tactics used by a plethora of groups, terrorism in its various manifestations and permutations is also intimately linked with armed conflicts as well as socio-political and economic characteristics in those societies where it is prevalent. Even though terrorist cells sometimes live isolated lives in underground movements, they are rarely entirely unaffected by the outside world. Assuming for a moment that the causalities of terrorism remain the same, we still live in an era of rapid societal change and globalisation of economy, culture and politics, and thus, the conditions, which cause terrorism to occur and to remain resilient, are rapidly changing. This has increasingly been acknowledged in much of the recent literature on terrorism. A couple of years before 9/11 Walter Laqueur argued that much of what we have learnt about terrorism in the past may be irrelevant to understanding the ‘new terrorism’.13

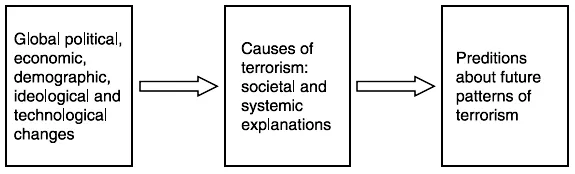

The present study aims at unearthing the forces shaping future terrorism patterns and understanding where they lead us. This will not be done by presenting one coherent picture or by outlining a number of possible scenarios. Instead, by exploring the complex picture of both permissive and countervailing forces, the book highlights most salient processes at work. In order to improve our ability to prognosticate about terrorism, this book offers a new research strategy or analytical framework for prediction. It relies on projecting trends in societal changes known to have an influence on terrorism, rather than projections based simply on previous patterns of terrorism. The framework consists of two main building blocks: first, propositions about future societal changes, and second, causes of terrorism. Put simply, those societal conditions, which appear likely to affect patterns of terrorism in one way or another are identified and studied with a view to predicting how these conditions are changing. On this basis it is possible to guess intelligently about the future of terrorism. A very simplified illustration of this research strategy is given in Figure 1.1.

The advantage of this framework is that many societal processes of change move slowly and are to a great extent determined by its previous evolution. Hence, they are predictable, and therefore useful, analytical tools for understanding the future. A pivotal part in the framework is causes of terrorism, that is various causal relationships linking societal patterns and characteristics to the occurrence and patterns of terrorism. As Martha Crenshaw has noted, prediction about terrorism can only be based on theories that explain past patterns.14 Conceptually, the approach is not unusual in similar fields of research. In an influential paper on the future of armed conflict, the editor of the Journal of Peace Research, Nils Petter Gleditsch, noted that there is a limit to what trend projection can tell us. We need to ‘ask ourselves what factors cause war, and whether these factors are improving or deteriorating [. . .].’15 At the end of this introductory chapter, I have provided a survey of existing ‘theories’ on the causes of terrorism, focusing on the nationalsocietal and the international/world-system levels. This survey provides us with the necessary tools to derive likely terrorism outcomes from a variety of future developments.

The present framework is attractive because of its simplicity and flexibility, and it may easily be adapted to encompass future theoretical findings on the causes of terrorism. Its strength lies in its ability to uncover possible future shifts, which do not seem very apparent, or even likely, by looking only at recent patterns of terrorism. Rather than aiming at presenting ‘the face of terror in 2020’, this study arrives, through its analyses, at a set of long-term implications for terrorism of current and future societal developments. Like other global-trend studies, there is no single trend or driver that completely dominates the future of terrorism. Nor will the trends identified here have equal impact in every region. Some trends also work at cross-purposes, instead of being mutually reinforcing.16 Still, through a survey of key global trends in six broad areas: globalisation and armed conflicts, international relations, the global market economy, demographic factors, ideological shifts and technological innovations, I am able to analyse what these drivers mean for the future of terrorism.

Figure 1.1 Predicting future patterns of terrorism.

The actual analytical units of this study are the ‘postulates’, which are basically general propositions about the future evolution of a particular phenomenon or societal process. The first of these postulates deals with the future evolution of globalisation. As will be seen, the literature offers several theories of causal linkages between globalisation and patterns of terrorism. In most cases, however, globalisation’s impact on terrorism is analysed in terms of its impact via intermediary factors such as state capacities, socioeconomic inequality and armed conflicts.17 Similarly, the future of armed conflicts is also examined in relatively broad terms with a view to understanding the implications for patterns of terrorism. As for the other categories of postulates, they are subdivided into more specific propositions, accompanied with sets of implications for terrorism patterns. For example, in the international relations category, one analytical unit is ‘democratisation’ and its postulate is: ‘the number of states in transition to democratic rule or which are neither autocracies nor fully fledged democracies will remain high and possibly increase.’ The postulates are formulated, based on a reading of relevant research literature, in this case, the voluminous literature on democratisation.

The initial selection of postulates was done intuitively, and they were subsequently refined, following several workshops in the Terrorism and Asymmetric Warfare Project Group with participation of invited scholars and practitioners. A set of selection criteria has also been applied: the postulates are assumed to correspond to or at least have a certain minimum of influence on one or more of the causal factors of terrorism; the predicted changes must be global in the sense that they involve more than just one country or one region; and the set of postulates should reflect the most likely future scenarios.18 Admittedly, postulates cannot be verified or validated. At best, one may reduce uncertainty by applying a set of methodological rules. Inconsistencies between various postulates should be clarified and avoided; results from contemporary research literature should, as far as possible, provide a basis for or give support to the postulates. The literature used for this study varies greatly. Recent social-science and political-science literature has been used extensively to understand causalities and dynamics, as well as to review specialist opinions on expected future developments within various fields. A great number of strategic assessments, trend studies and other futuristic...