![]()

1

Corruption, economic growth and globalization

An introduction

Aurora A.C. Teixeira

Corruption is a severe impediment to economic growth, and a significant challenge for developed, emerging and developing countries.

(G20 Seoul Summit 2010)1

The attention of society, in general, and policy-makers, in particular, has increasingly focused on public sector corruption—the abuse of public office for personal economic gain (Rose-Ackerman 1978)2—as a key determinant of countries’ economic performance (Hessami 2014; Oberoi 2014).

A European Commission report revealed that corruption affects all EU countries and costs the bloc’s economies around 120 billion euros ($150 billion) a year (EC 2014). Other estimates show that the cost of corruption equals more than 5 percent of global GDP (US$2.6 trillion) with over US$1 trillion paid in bribes each year (OECD 2014).

In a context of economic austerity and increasing social inequalities, citizens are less and less indifferent to corruption (Gómez Fortes et al. 2013; Hessami 2014). Protests against corruption, both on the Internet and in street demonstrations, have gathered massive support and followers all over the world (Sloam 2014), especially in countries recently hit by corruption scandals (e.g., Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Slovakia, Thailand, Turkey and Ukraine).3

A basic premise is that corruption tends to occur where rents exist and public officials have discretion in allocating them (Mauro 1998b). The essentials about corruption are neatly revealed in Klitgaart’s (1988) formula: corruption = monopoly + discretion − accountability. For instance, the processes of privatization (of public or state companies) have themselves produced situations whereby some individuals (e.g., ministers, high-ranking political officials) have the discretion to make key decisions while others (most notably, managers and other insiders) have information that is not available to outsiders, thus enabling them to use privatization to their benefit in a context deprived of transparency and accountability. Such abuses have been particularly significant in the transition economies (Tanzi 1998; Achwan 2014; Duvanova 2014), where chaotic corruption seems to prevail (Mauro 1998b).

As shown in Chapter 2, theory is divided over the effects of corruption on economic growth—the “grease the wheel”/“efficient corruption” argument (Leff 1964; Beenstock 1979) versus the “sanders”/private and public investment misallocation argument (Mauro 1998a) or, more recently, the “gamble” hypothesis (Saastamoinen and Kuosmanen 2014). However, there is a growing consensus based on the empirical literature that corruption is detrimental to economic growth (Bose 2010; Ahmad et al. 2012). While the causality underlying this relationship is likely to run both ways, the majority of researchers contend that it is primarily running from corruption to economic growth rather than in the opposite direction (Grochová and Otáhal 2013). Notwithstanding, the two-way relationship has the potential of setting in motion a virtuous circle, where product and productivity gains from curtailing corruption can be invested in human and civic capital necessary to make further progress in reducing corruption, leading to more production and productivity gains (Mehanna et al. 2010; Dzhumashev 2014).

The negative impact of corruption on economic performance can occur through a host of key transmission channels, most notably investment, including Foreign Direct Investment (Pellegrini and Gerlagh 2004), competition (Jain 2001b), entrepreneurship (Ugur 2014), government efficiency (Otáhal 2014), and human capital formation (Mauro 1998b). Additionally, corruption affects other important indicators of economic performance such as the quality of the environment (Johnson et al. 2011), personal health and safety status (Ahmad et al. 2012), equity (income distribution) (Tanzi 1998), and various types of social or civic capital (“trust”) (Boycko et al. 1996)—which impact significantly on economic welfare and a country’s development potential (Aidt 2009).

Corruption undermines public trust in the government, hampering its ability to fulfill its core task of providing acceptable public services and an adequate environment for private sector progress (Bjørnskov 2011). The delegitimization of the state associated with corruption leads to political and economic instability (Khan 2007), resulting in general uncertainty which negatively impacts on the willingness and ability of private business to commit to a long-term development strategy, hindering the countries’ sustainable development paths (Saastamoinen and Kuosmanen 2014).

Corruption may be more prevalent in poor, non-democratic or politically unstable countries (Cason and Ramaswamy 2003; Odi 2014). However, given increasing globalization, corruption in less developed countries is likely to affect not only their economic growth but also that of more developed countries through the impact it has on investments from foreign-owned firms in less developed countries (Keig et al. 2014). Thus, the issues of corruption and globalization are profoundly interconnected (Asongu 2014), and are characterized by nonlinearities (Lalountas et al. 2011), as established in Chapter 3. Indeed, as a result of globalization and the growing awareness among multinational companies of the hazardous impact of corruption on investment, growth and poverty reduction and, therefore, on successfully achieving their goals, the phenomenon of corruption has come to be regarded as an effective barrier to global, regional and local economic development (Tanzi 1998; Javorcik and Wei 2009; Teixeira and Grande 2012; Ugur 2014). Thus, corruption is not only an obstacle to social development but also to economic growth because it drives the private sector out (Tanzi 1998). When it does not, in most cases, it makes investing in a corrupt country more expensive than in a transparent one (Saastamoinen and Kuosmanen 2014). By lowering economic growth, it breeds poverty and inequality over time (Mauro 1998b; Gupta et al. 2002; Oberoi 2014). At the same time, poverty itself might foster corruption (see Chapter 9) as poor countries are unable to devote enough resources to setting up and enforcing an adequate legal framework and/or developing an education infrastructure conducive to cultivating better informed and ethically aware individuals (Pitsoe 2013; Justesen and Bjørnskov 2014).

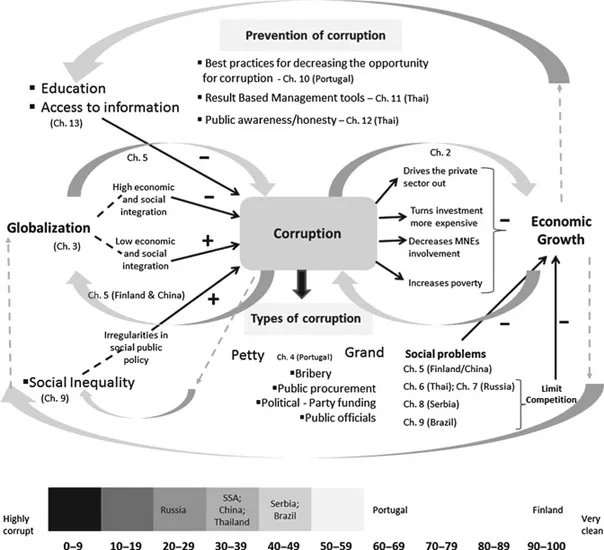

The present volume offers a novel, coherent, and multidisciplinary–multidimensional–multi-country account of corruption, addressing the complex linkages between corruption, economic growth and globalization (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Corruption, economic growth and globalization—portraying the book’s structure.

Note: The classification of corruption is based on the Corruption Perception Index, 2012–14.

Source: Transparency Index.

The book combines distinct perspectives by analyzing corruption through the lenses of economics, international business, law, criminology, psychology and sociology, highlighting the nonlinearities and two-way causality among these three phenomena (cf. Chapters 2–3), as well as the relevance of taking into account the types of corruption (cf. Chapters 4–9) when assessing its impact on the economic performance of countries. It provides in-depth, empirical insights into quite disparate contexts in terms of perceived corruption, including very high (Russia, sub-Saharan African countries, China, Thailand), middle-high (Serbia, Brazil), middle (Portugal), and very low (Finland) corruption contexts. Finally, it addresses the topic of corruption prevention based on the evidence and experiences of some countries that have been facing noticeable corruption problems for a long time (Tanzi 1998): Portugal (Chapter 10), Thailand (Chapters 11 and 12) or sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries (Chapter 13).

In terms of structure, the book is divided into three parts. Part one provides a theoretical and empirical account of the linkages between corruption, economic growth and globalization. Part two, focusing on distinct mechanisms, presents evidence on how different types of corruption (grand versus petty) are likely to impact on the economic performance of countries. Part three describes the measures and policies deployed in some countries to prevent and control corruption setting the path for sustainable growth strategies.

Within part one, Chapter 2 provides a theoretical overview on the “tribes” of (the economics of) corruption and (endogenous) economic growth based on Hoover’s (1991) “Tribe and Nation” perspective. Aurora Teixeira and Sandra Silva then complement this theoretical account with a bibliometric exercise which details the main contributions from research in these fields, and assesses the possible emergence of an intersecting research pattern between both “tribes.” In Chapter 3, Joseph Attila thoroughly scrutinizes the nonlinearity between globalization and corruption, demonstrating that the relationship between corruption and globalization might not be as simple as suggested in the current literature. Applying econometric tools to a sample of 122 countries from 1990 to 2006, Attila shows that globalization did not benefit most sub-Saharan African countries because their participation in the internationalization process has not been sufficiently high. He further stipulates that countries need to achieve a minimum level of economic and social integration before they can take advantage of the reducing effect of globalization on corruption and, ultimately, on sustainable economic development.

The effect of corruption on growth tends to vary among countries and the type of corruption (Ugur 2014). Little evidence exists, however, on which types of corruption are more deleterious and should be tackled first (Shah and Schacter 2004; Winters et al. 2012). Country-specific studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that high-level and low-level corruption tend to coexist and reinforce each other (Mauro 1998a; Mashali 2012). One of the most well-known and widely used taxonomies of corruption is the one that distinguishes between bureaucratic or “petty” corruption and political or “grand” corruption (Mauro 1998b; Jain 2001b; Nystrand 2014). Specifically, bureaucratic corruption includes “corrupt acts of the appointed bureaucrats in their dealings with either their superiors (the political elite) or with the public” (Jain 2001b: 75). Petty corruption is the most common form of bureaucratic corruption often involving the payment of a bribe to bureaucrats by the public either to receive a service to which they are eligible or to speed up a bureaucratic procedure; it usually involves smaller sums of money (than grand corruption) and typically more junior officials. Political or grand corruption is generally considered the corrupt acts of high-ranking officials or “the political elite by which they exploit their power to make economic policies” (Jain 2001b: 73), usually involving substantial amounts of money.4

Corruption as “the way things are” or petty corruption is, in general, less condemned by citizens than grand corruption (Nystrand 2014). Indeed, the former is often seen as a system of which everyone is part and therefore people do not judge each other’s involvement in this type of corruption, while grand corruption benefits a few by considerable amounts of money, which greatly distresses people. This also seems to be the case in Portugal. Gabrielle Poeschl and Raquel Ribeiro (Chapter 4) analyzed the responses of 182 Portuguese individuals and found that people are not fully aware of the social costs of corruption (both petty and grand). In general, Portuguese citizens tend to disapprove of corrupt practices, especially involving grand corruption, “and reluctantly accept lenient verdicts in the cases of grand corruption,” but fail to demonstrate a “shared social responsibility” able to overcome such alarming and growth inhibiting phenomena.

Mauro (1998b) further distinguishes well-organized/predictable corruption from chaotic corruption. He claims that the latter may be the most deleterious in terms of private investment and entrepreneurship and, ultimately, for the economic growth of countries. This is justified on the basis that under a well-organized/predictable system of corruption, “entrepreneurs know whom they need to bribe and how much to offer them, and are confident that they will obtain the necessary permits for their firms;” moreover, “a corrupt bureaucrat will take a clearly defined share of a firm’s profits, which gives him an interest in the success of the firm” (Mauro 1998b: 13).

The characteristic of the predictability of corruption in China explains, according to Päivi Karkuhnen and Riitta Kosonen (Chapter 5), why corruption does not have a stronger negative impact on (foreign) investment in this country. These authors, adopting the neo-institutional organization theory, identify the strategic responses that Finnish firms (originating from a country recurrently ranked among the world’s least corrupt) take in their Chinese subunits to cope with corruption as a feature of the local institutional environment. Based on 60 interviews with the management of Chinese subsidiaries of Finnish firms, collected between 2003 and 2011, they discovered that although “corruption is recognized as a common feature of Chinese society and economy, its influence on foreign firms is not as significant as could be expected.” Additionally, it is recognized that “few firms can afford to completely ignore the external pressures from the corrupted institutional environment.” However, instead of engaging in corrupt practices, foreign firms “substitute corruption with reliance on personal networks.” Thus, “good personal relations with high-level public sector officials can be used to shortcut the bureaucracy as an alternative to speed-up payments.” An important strategy by Finnish firms investing in China to circumvent corruption is to delegate the interactions with potentially corrupt Chinese stakeholders to the local staff. Such a strategy “helps Finnish firms and their potential expatriate management in China to simultaneously conform to the home country’s anti-corruption institutional pressures and the external pressures from the host environment to do business ‘in the local way.’ ”

Networks and, more precisely, interpersonal relationships for social, business, and other activities are also key to understanding corrupt activity in Thailand, as Sirilaksana Khoman (Chapter 6) insightfully establishes. Resorting to cases studies to determine the pattern of patron–client networks that affect procurement, the author shows that the network relationship in Thai public procurement constitutes “fertile ground” for both petty and grand corruption. It is important to underline that procurement spending, that is, the purchase of goods and services on the part of the government, has traditionally lent itself to frequent acts of high-level corruption (Tanzi 1998). Such acts escalate government expenditures and distort allocation of government expenditure away from education, health and maintenance infrastructure (Ahmad et al. 2012), which is likely to severely undermine the growth prospects of countries.

Andrey Ivanov (Chapter 7) also deals with public procurement corruption, in this case, in Russia. With the expectation of fostering suppliers’ involvement in “the procurement process, to reduce corruption, and to hinder the possibility of collusion by suppliers, which would subsequently lead to improved competition in auctions and to larger price reductions,...