eBook - ePub

The Royal Navy in the Falklands Conflict and the Gulf War

Culture and Strategy

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book suggests that institutional culture can account for a great deal of the activities and rationale of the Royal Navy. War highlights the role of culture in military organizations and as such acts as a spotlight by which this phenomenon can be assessed seperately and then in comparison in order to demonstrate the influence of institutional culture on strategy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Royal Navy in the Falklands Conflict and the Gulf War by Alistair Finlan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Culture and the Royal Navy

In this high-technology age of cruise missiles, satellite-guided bombs and depleted-uranium tank shells,1 surprisingly, given the limitations of the flesh, people are still the most important elements in warfare. Apart from the former stemming from the imagination of the latter, the art of war remains the realm of specialists in global society. The effects of fighting may influence millions but the warrior in whatever guise (soldier, guerrilla, terrorist) represents a minority occupation in the twenty-first century.2 These individuals have joined a profession in which the fundamental purpose is to apply violence (often lethal) to achieve political ends.3 Like all employment, the career span of a warrior is limited by age, with few exceeding more than forty years, but unlike in most other occupations, warriors may never practise their skills. War is a haphazard event in international relations not only in terms of occurrence but also duration. In extended times of peace, some military specialists will never hear the sound of battle whereas others will always live under the shadow of the sword. Regardless of circumstances, the profession of arms continues whether in peace or war and it produces a certain type of global citizen who is attuned to a different environment to that which the majority of society takes for granted.

MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS

The armed forces are institutions in their own right or in other words represent some of the most important forms of organization within a state. Organizations can be described as collections of people within society working toward a common goal or within a common framework. Institutions are created by nations and provide the foundations on which the political structure resides. They are specifically designed for a purpose whether it be collecting money like the Treasury or providing a force option within the maritime environment, which is the function of the Royal Navy. Organizations of whatever form do not have the same level of legitimacy that institutions possess within society. Legitimacy is often derived from age, and state institutions tend to be very old and in a social sense generate an imbued trust in society. Military institutions need society to provide recruits but in the case of regular non-conscript forces, the trust element in the relationship between the civil and military is very important. Joining the military is universally acknowledged as employment with a risk factor to life expectancy that is higher than for most non-military organizations. At the societal level, certainly in respect to Britain, families must have confidence in the armed forces to look after the future generation despite the increased work-related risks.4

The Royal Navy is a very old military institution that has been in existence for hundreds of years. As such, it has served Britain in various forms of statehood from the absolute monarchy to the modern democratic constitution. The link with the highest levels of political governance has traditionally been strong. To this day, the power cables with the royal family (the former rulers of the nation) are still embedded in the Royal Navy, reflected in the position of Lord High Admiral, the symbolic head of the service, that is occupied by the current Queen Elizabeth II. Prince Charles, the heir to the throne, and Prince Andrew were both officers within the service.5 Remarkably, the institution even introduced the head of state to her future husband: the Queen met Prince Philip in the grounds of Britannia Royal Naval College.6 The role of the Royal Navy in relation to the nation have been inextricably linked to Britain’s island status. The surrounding sea has always possessed a Janus nature: on the one hand, a source of trade and resources like fish (now gas and oil) but on the other, a conduit for hostile invaders. Invasions in British history have tended to be catastrophic events for the indigenous political administrations from the time of Julius Caesar in 55BC to the successful assault by William the Conqueror in 1066. From this perspective, the maintenance of a viable navy in order to pre-empt a land engagement and ensure the survival of the state has been the ultimate raison d’être of the Royal Navy. This purpose has been perpetuated within the institution and demonstrated itself to be of critical importance to the security of Britain for several centuries, a span that includes the first 50 years of the twentieth century.7

CREATING A MILITARY CULTURE

The inner workings of military organizations are shrouded in mystery to outside observers due to their exclusive nature. In modern democracies with professional, all-volunteer armed forces, only a select few are chosen to join the ranks of the military. In Britain, for instance, approximately 37,000 people (trained) serve in the contemporary Royal Navy, and without universal military conscription, it means that just a fraction of the 60 million inhabitants of the island experience close contact with the service. In the recent past, the relationship with society was much closer, reaching a peak with World War II when nearly one million personnel served in the Royal Navy.8 The current isolation has been further reinforced by the threat of domestic terrorism for the last 30 years, and so the sight of uniformed personnel has become a rare event in civil society except for ceremonial duties. Military units have been forced to tighten the security surrounding their perimeters with the inevitable consequence that the natural gulf with society between civilian and service personnel has widened considerably in these years.

Behind this virtual wall, the British armed forces have continued to prepare for conflict. Access or a lack of it has not altered their primary purpose that remains to fight in the interests of the state or as Bernard Brodie once remarked, ‘to win wars’.9 This may seem like an excessive emphasis on functionality but it is the innate core around which military culture is formed. In the field of international relations, a great deal of contemporary research is beginning the focus on the role of culture within these organizations.10 A good starting point is Alastair Iain Johnston’s definition of culture:

Culture consists of shared decision rules, recipes, standard operating procedures, and decision routines that impose a degree of order on individual and group conceptions of their relationship to their environment, be it social, organizational, or political. Cultural patterns and behavioural patterns are not the same thing. Insofar as culture affects behaviour, it does so by presenting limited options and by affecting how members of these cultures learn from interaction with the environment. Culture is therefore learned, evolutionary, and dynamic, though the speed of change is affected by culturally influenced learning rates, or by the weight of history. Multiple cultures can exist within one social entity (i.e., community, organization, state, etc.) but there is a dominant one that is interested in preserving the status quo. Hence, culture can be an instrument of control, consciously cultivated and manipulated.11

The critical question is that of how a military culture can be assessed or measured. Public displays of pomp and ceremony merely reveal a carefully orchestrated veneer suitable for wider society. A more in-depth examination of a military establishment creates an interesting methodological challenge for researchers seeking to explore the visible and the invisible aspects of an armed service. Uniformity, order and identity predominate the atmosphere that is punctuated by consistency of behaviour with (service-specific) idiosyncratic language. Elizabeth Kier in her study of French and British military doctrine in the inter-war period adopts an ‘interpretive approach based on archival, historical and other public documents’.12 This study too utilizes such material but in addition illustrates how culture is formed and perpetuated among the officer corps of the Royal Navy at the very earliest stage based on first-hand observation.13 The focus on the officer corps is deliberate because it provides the leaders who make the key decisions within the organization. As Legro has noted, ‘cultures, once established, tend to persist. Those individual members of a culture who adhere to its creed tend to advance in an organization and become the dominant culture’s new protectors.’14 It is through people, or more specifically officers, that military culture is replicated in a uniform manner over extended periods of time.

THE ROYAL NAVY

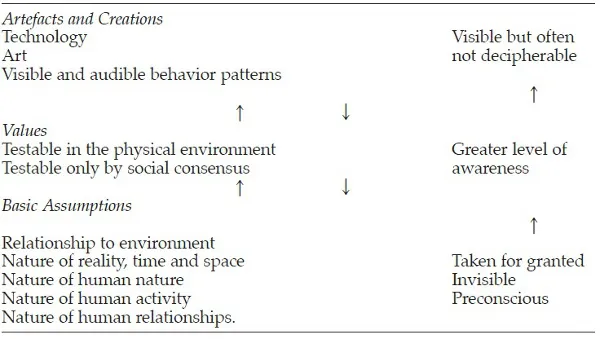

Britannia Royal Naval College, colloquially known as ‘Dartmouth’, is the place where the cultural regeneration process occurs for newly joined officers. It is an initial training establishment that steeps the new recruits in the beliefs, norms and values of the service for a year before determining whether they are suitable for further training and careers as naval officers. Highlighting the means by which the Royal Navy generates a cultural format requires a multi-disciplinary approach. By itself, the college is just a building, albeit a magnificent one, built during an age when the Royal Navy was the most powerful navy in the world, but it is merely – in modern terminology – the hardware. Of more significance is the software, or the process of converting a civilian to a military officer. In common with much of the recent research, a sociological perspective provides a useful means of analysis, particularly that suggested by Edgar Schien who offers an excellent model for how an organizational culture can be illustrated layer by layer. This model shows that at the surface lie artefacts and creations such as technology. Just below the surface can be found the inherent values or the sense of what ‘ought’ to be within the organization. At the heart of the organization reside the basic assumptions and beliefs, which are taken for granted and invisible.15

Figure 1. Levels of Culture and Their Interaction

Source: E. Schien, Organizational Culture and Leadership, p. 14.

Making a Naval Officer

Military leaders are artificial creations, shaped and manipulated by institutions to conform to their own image. As John Garnett reminds us, ‘there is widespread agreement that one of the things that distinguishes human beings from animals is that most of their behaviour is learned rather than instinctive’.16 With regard to the Royal Navy, new officer cadets endure a ‘formatting’ process that could be described as intense indoctrination. The civilian or potential officer is immediately displaced from mainstream British society in a physical and psychological sense by being immersed in an all-encompassing military environment. Quite quickly in this setting, the relationship between civilian and military though not explicitly expressed becomes one of ‘us and them’, which is particularly noticeable among new recruits after just 15 weeks of training. An individual’s entire life structure is completely altered to fit in with the collective whole. The process of assimilation stretches from personal appearance, such as haircut, dress and bearing, to attitudes and beliefs. Kier argues that, ‘the military’s powerful assimilation processes can displace the influence of the civilian society’.17 The Royal Navy arguably achieves this goal in its training process in a remarkably short space of time. For the first weeks of training, no new recruit is allowed on a ‘run ashore’.18 All are confined to the establishment and worked for periods that average 16 hours a day. Gradually through instruction, osmosis and environment, the recruit becomes navalized. Dropouts, and those considered unfit for naval life, are quickly excluded from the primary group.

Identity within individual divisions and classes is promoted on a daily basis. Legro reinforces this argument by stressing that, ‘people are socialized by the beliefs that dominate the organizations of which they are part. Those who heed the prevailing norms are rewarded and promoted. Those who do not are given little authority or are fired.’19 Competition with other recruits and other units is inculcated from day one and it remains an essential element of a naval officer’s career. If at any stage a naval officer or a cadet leaves the service, then the bonds are broken for ever and that person no longer counts for anything within the institution: a brutal selection process that has honed generations of naval officers in the jungle of advancement to higher ranks. By the time a naval officer reaches the highest rank of the Royal Navy, that of ‘First Sea Lord’, then the institution will have selected an individual who reflects the beliefs and assumptions of the service to a greater degree than his contemporaries.

The social separation from society is most effectively achieved through the use of institutionally specific language. Language probably creates the most divisions in human relations in global society. It heightens a sense of what postmodernist writers would call ‘otherness’.20 The language of the Royal Navy revolves around the terminology associated with ships. Toilets are ‘heads’. The dining room becomes the ‘mess decks’. The separation from...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- SERIES EDITOR’S PREFACE

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- ABBREVIATIONS

- 1. CULTURE AND THE ROYAL NAVY

- 2. CULTURE, STRATEGY AND THE FALKLANDS CONFLICT

- 3. CULTURE AND OPERATIONS IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC

- 4. CULTURE, STRATEGY AND THE GULF WAR

- 5. CULTURE AND OPERATIONS IN THE PERSIAN GULF

- 6. CULTURAL COMPARISONS: THE FALKLANDS CONFLICT, THE GULF WAR AND THE FUTURE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY