eBook - ePub

New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India

About this book

This book presents a comprehensive analysis of the similarities and differences of contemporary human resource management systems, processes and practices in the two increasingly important economic great powers in Asia. It covers the full range of human resource management activities, including recruitment, retention, performance management, renumeration, and career development, discusses changing industrial relations systems, and sets the subject in its historical, social and cultural contexts. It examines newly emerging strategies, and asssesses the extent to which human resource management systems in the two countries are coverging or diverging.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Models of Human Resource Management in China and India by Alan R. Nankervis,Fang Lee Cooke,Samir R. Chatterjee,Malcolm Warner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios étnicos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Asian century

The shift of global economic power to China and India

Introduction

In recent years there has been rigorous discussion about the unexpected and relatively rapid emergence of China and India (or the so-called ‘Asian century’) as models of global economic growth, in counterpoint to the historical dominance of world markets by the United States and, to a lesser extent, Japan. Their comparative insulation and swift recovery from the ravages of the 2009 global financial crisis (GFC) have been evidenced as clear indicators of the strength of their contemporary economies (Anonymous 2010a; De Carlo 2010). As Yeates (2010: 3) explained,

Asia (notably, China and India) … avoided many of the toxic debt products that wreaked havoc in other parts of the world … (and) Asian countries played a greater role in response to the recession than in past crises because the G20 became the key forum for leaders, replacing the G7 (our italics).

However, there were some effects of the GFC. In India, for example, the rupee was devalued; and in China foreign direct investment (FDI) declined by 20 per cent in early 2009, economic growth fell to around 6 per cent, and an estimated 6.7 million jobs were lost with the closure of approximately 67,000 factories (de Haan 2010: 72).

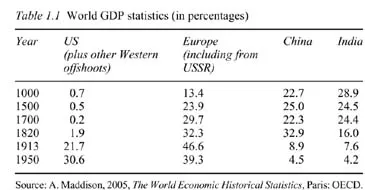

Underlying the optimistic commentaries on the implications of the current surge in the economic (and thereby geopolitical) power of China, and to a lesser extent India, is an arguably over-simplistic notion. Based upon a misreading or an ignorance of history, it has often been assumed that the present remarkable growth patterns of China and India in contrast to those of the United States, Japan, or Western Europe, are unique or at least unparalleled in the recorded past. This is a flawed notion, as during the late seventeenth century both China’s and India’s relative wealth and geopolitical power far surpassed that of the Western world. In the early 1800s, for example, the two countries contributed nearly half of the world’s income. As Dalrymple (2007: 1) pointed out, ‘historically, South Asia was always famous as the richest region of the globe .... At their heights during the 17th century, the sub-continent’s fabled Mughal emperors were rivaled only by their Ming counterparts in China’. He further suggested that it was colonialism which ‘slowly wrecked the old trading network and imposed with their cannons and caravels a Western imperial system of command economy’ (Dalrymple 2007: 1). Thus, rather than being a new phenomenon, the current economic growth in both China and India represents little more than a ‘return to the traditional pattern of global trade’ (Kelly, Rajan and Goh 2006; Mahbubani 2008).

Whilst Dalrymple’s thesis (2007) is questionable, as the present global economic environment is far more complex and interconnected than in earlier periods, the current economic growth in China and India should be perceived as a resurgence in their global prominence rather than a completely new phase of economic development. In recent years the joint contribution of China and India has amounted to approximately a fifth of global income, although there are predictions that it will reach one-third by 2050 (Gupta, Govindarajan and Wang 2008). Table 1.1 provides some comparisons between the gross domestic product (GDP) of China and India compared with the US and Europe between 1000 and 1950. As the Table demonstrates, India and China have re-emerged as significant global economic forces, albeit from a low base in the early 1900s.

The key themes of this chapter and throughout the book are:

- The diffusion of macro level strategies to enterprise levels in China and India.

- The re-emergence of China and India in the context of the recent global financial crisis.

- A strategic focus on bilateral collaboration, linking one-third of the global population and a quarter of the world's talent.

- Future Chinese and Indian collaboration through human resource development and research and development.

- Trust and learning as the bases for cooperation in building new industries and innovative capacities.

Economic growth indicators in China and India

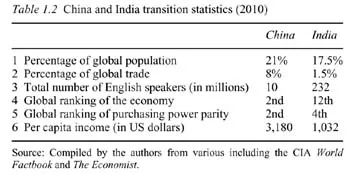

Whilst at least some of the exaggeration surrounding the developments has been driven by the self-promotion (or wishful thinking) of authors from these two neighbouring countries (Ramesh 2005; Huang 2010), many external observers have also noted their above average development and economic growth statistics. Table 1.2 compares some of these pertinent indicators.

A 2008 report by the Bank of New York Mellon (Anonymous 2008a: 4), for example, concluded that ‘... the two economies will account for up to 50 per cent of global consumption ... combined, China and India will be the largest worldwide producers and consumers of coal, steel, cement and non-ferrous materials’. A more recent report in The Economist predicted that 40 per cent of world economic growth would derive from the two countries (Anonymous 2010a), and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggested that ‘Asia – spurred on by booming exports and the rise of China’s and India’s middle class – would become the world’s biggest economic region by 2030’ (Yeates 2010: 3). The IMF’s graduated growth rates differentiate between China and India, with China’s rates predicted to be 8 per cent (2010), 12 per cent (2020) and 22 per cent (2030) respectively, whilst India’s are considerably smaller – namely, 2 per cent, 4 per cent and 5 per cent (Yeates 2010). This latter prediction is somewhat at odds with the figures for the third quarter of 2009 (in the midst of the GFC) during which period India achieved nearly 8 per cent growth, transforming itself ‘from a land of elephants and snake charmers to that of an information technology powerhouse and an emerging economic giant’ (Gupta and Wang 2009a: 86).

Other indicators of China’s impressive economic growth and transformation: it is the second largest global economy now with a GDP greater than Japan; GDP has ‘multiplied tenfold’ in 30 years to almost US$ 9 trillion; since 2000, it has displaced the US to absorb the largest amount of exports from Korea and Japan, especially textiles, garments and electronics; and it is rated twenty-seventh in the World Economic Forum’s competitiveness index. Further, China contains the world’s biggest car market (14 million sales annually); it consumes a fifth of all global energy and 46 per cent of the world’s coal, together with double the amount of crude steel of the EU, US and Japan combined. Finally, it is the world’s largest producer of IT products, the biggest microchip market, and has developed growing expertise in solar cell and semiconductor manufacturing, shipbuilding and biomedical technology (compiled from various sources, including Anonymous 2010c: 9; Ferguson 2010: 21; Green and Kliman 2011: 37; Lee and Kim 2011: 56, 59; Park 2011: 15; Zhang 2011: 23). These optimistic predictions and prognostications should, however, be treated with some caution because of the often inaccurate or misleading statistics provided by Chinese (and other) agencies, and the contestable bases upon which they are built, together with the plethora of their underlying assumptions. As Dixon (2011: 3) explains,

China is so big that its economic success is applying a brake to further progress. Not only has this helped push up the price of commodities, which are hugely important for China’s manufacturing-orientated economic model .... two (other) big challenges ... the need to switch gears to a new consumption-led economic model, and the quest for social stability.

Whilst India’s economic indicators are not quite as remarkable as in China, there are also important signs of its growth and development, including the presence of many large Indian companies in Forbes 2010 Top 500 companies (Indian Oil, Reliance Industries, the State Bank of China, Bharat Petroleum, Hindustan Petroleum, Tata Steel and Tata Motors) and even more in the Global 2000 companies. Indian multinationals employ more than 200,000 people in their global operations (for example, Patni Computer Systems, Ranbaxy Labs, Tata Tea, Dr. Reddy’s Labs, GHCL and Bharat Forge – Chatterjee 2010). With respect to the growth in intra-regional trade between China and India, the indicators are just as impressive – approximately US$ 60 billion in 2010 – which was 230 times greater than in 1990 (Anonymous 2010a, b). Table 1.3 illustrates the comparative growth in external FDI outflows between China and India.

However, whilst China’s ‘competitive edge is shifting from low-cost workers to state-of-the-art manufacturing, India is creating “world-class innovation hubs”’ (Nelson and Choudaha 2006: 2). China ‘has (also) managed to convert the advantage of a growing workforce into a virtuous loop of creating productive jobs that lead to higher savings, investment and growth’ (Kucukakin and Thant 2006: 10). Some factual comparisons and contrasts between China and India both highlight their similar and different characteristics and suggest implications for their potential collaboration or competition in regional and global environments. Thus, both China and India have large land masses (China is 9.5 million and India is 3.3 million square kilometres); and similar population sizes (1.4 million versus 1.1 million); but there are significant discrepancies with respect to GDP real growth (11 per cent versus 9.5 per cent); GDP per capita (US$ 7,800 versus US$ 3,800); relative export income (US$ 974 billion versus US$ 112 billion); and research and development expenditure (2.5 per cent GDP versus 1.5 per cent GDP) (Y. Huang 2008). As Murthy (2009: 250) observed:

Every year, China produces 600,000 engineers while India produces 450,000. In comparison, USA produces 70,000 engineers a year. Several global corporations have consequently realized the importance of sourcing this global talent. For example, General Electric (GE) has set up an R&D laboratory, the largest of its kind outside the USA, in Bangalore; over 1,000 GE researchers work on leading-edge solutions out of this facility. Microsoft has established R&D facilities in China and India.

China and India – cooperation or collaboration?

An important underlying notion which requires some exploration is the concept of ‘Chindia’, first coined by an Indian politician, Jairam Ramesh, in his 2005 book entitled Making sense of Chindia: Reflections on China and India. Whilst Ramesh’s interpretation of Chindia is quite loose and broad, involving a blend of economic agreements, joint ventures and collaborative economic projects, subsequent observers have extended his vision to higher levels, ranging from basic facts to more extreme predictions. Thus, some observe that China and India have complementary economies – ‘China, through its burgeoning factories, is the world’s workshop. India, with its fast-growing IT and outsourcing firms, is becoming the world’s back office. With Chinese hardware providing the orchestra and Indian software writing the score, surely they can make beautiful music together?’ (Sen 2005: 1).

Other authors present a more complex view, suggesting that formal agreements between the Chinese and Indian governments to preserve their present niche industry expertise – for example China’s specialization in fabricated products versus India’s strength in raw or semi-processed commodities – would be mutually beneficial. China’s export-oriented industrial production versus India’s commercial services (Anonymous 2007b; Holslag 2008) – together with the acceptance of competition in other industry sectors (automobiles, machine tools) - may represent a form of pragmatic collaboration (or merely a China–India Free Trade Agreement) which ‘prioritizes the attraction of investments and the access to foreign markets, with stability at the borders as a precondition’ (Anonymous 2007a: 5). Most of these authors acknowledge the crucial pre-conditions of stasis in the division of labour between China and India, and a stable mutual political and military relationship in the pursuit of these objectives, neither of which seem likely in the foreseeable future.

Optimistic observers have suggested that Chindia could lead to ‘a division of labor ... that is mutually beneficial, optimizes the effectiveness of production and stimulates commercial exchange’ (Holslag 2008: 2), or that the economic and political relationships between China and India will transform into a form of intraregional symbiosis (Anonymous 2007a). What is significant in the concept of ‘Chindia’ is the suggestion of complementarity between China and India. However, with complementarity comes competition. As an example, with an original US$ 200 million investment from Toyota, the Indian auto components industry has become a global player second only to China. As Meredith (2007: 91) observes, ‘… India’s auto parts exports have been growing by 25 percent a year and are expected to rival China’s by 2015. Every auto parts factory opened could mean hundreds of new jobs for India’s ranks of unskilled workers’. In more recent times, there have been alternative conceptions such as ‘Chimerica’ (Aiyar 2009) or ‘Amerindia’, reflecting both the recognition of the global economic prominence of China and India, and the apparent psychological need for some form of bilateral relationship between Asia and the US. It appears however, that China’s geopolitical imperatives are more concerned with multilateral than bilateral cooperation, ‘a vision which competes directly with the US (and Indian) approaches’ (Choi 2011: 45).

Unfortunately, these notions fail to factor in the historical and current difficulties in the relationships between China and India – for example, the dynamic changes taking place in industry structures in both countries; their diverse demographics and socio-cultural characteristics; frequent tensions and conflicts; and global power imbalances which exist between the two nations. The seeds of future dissonance may lie in the very ideological, geopolitical, economic, social and cultural factors which are inherent in the apparent complementary characteristics. As both countries continu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Authors

- 1 The Asian century: the shift of global economic power to China and India

- 2 Cultural and traditional legacies, leadership values and human resource management principles

- 3 Human resource management in transition

- 4 Transformation in industrial relations

- 5 Changing talent attraction and retention strategies

- 6 Performance management, human resource development, rewards and remuneration systems

- 7 The dynamic human resource management architecture of Chinese and Indian global organizations

- 8 Towards new models of human resource management

- Bibliography

- Index