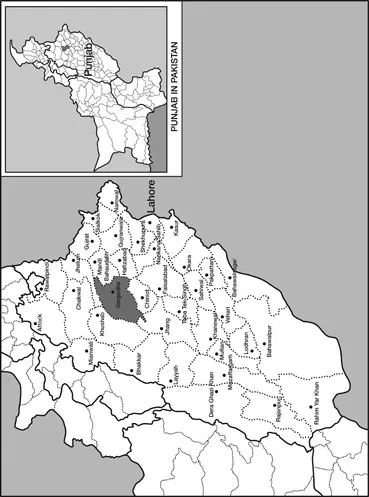

District Sargodha

The Punjab is home to the five rivers that give the province its name.1

The river Jhelum serves as the Punjab’s Western boundary with the Sutlej serving as the region’s Eastern boundary. In between these two rivers lie the Chenab, the Ravi and the dry bed of the Beas River.2 The areas between these rivers, known as doabs,3 constitute some of the most fertile land in all of Pakistan. The research for this book was carried out in the village of Bek Sagrana in the central Punjabi district of Sargodha located in the Jech doab, demarcated by the Chenab River to the East and by the Jhelum River to the West. According to Wilder, the Central Punjab is the Punjab province’s

… political, economic and cultural centre. It is the most urbanized, industrialized, agriculturally productive, and densely populated of the four regions of the Punjab. The sixty-one National Assembly Seats of central Punjab comprise more than half of the total seats of the Punjab and more than a quarter of the entire country’s seats. The key to success in Punjab politics and to a considerable extent Pakistani politics lies here.

(Wilder 1999: 34–37)

Sargodha is one of the districts that comprise the central Punjab, with five national assembly seats and eleven provincial assembly seats.4 Subsequent to canal colonisation that began in 1885, the area became one of the most agriculturally productive areas in Asia5 as well as the most densely populated area of the Punjab.6 Fertile land and an extensive irrigation system contributed to making the central Punjab the centre of Pakistan’s green revolution. In addition to being the richest region of the Punjab agriculturally, it is also the most industrialised one. In 1989, 71.9 per cent of the Punjab’s industry was located in the central Punjab, principally concentrated in the cities of Lahore, Faisalabad and Gujranwala (ibid.: 40).

As a result of canal colonisation the Sargodha district became a major producer of cotton, wheat, barley, maize, millet, rapeseed, and pulses. By 1947 the Sargodha district had become one of the largest agricultural hubs in Asia, with a major market for grain (particularly wheat) and 10 large and well-equipped cotton ginning factories. At the time of independence, when Pakistan emerged from partition with a poor industrial base, the district was a major contributor to Pakistan’s tax revenue and a major focal point of foreign exchange. Agriculture in the district received a further boost during the green revolution starting in the 1960s. During the 1980s the extensive irrigation system of the district made it possible for many landlords to start substituting citrus cultivation, requiring significant amounts of irrigation, for cotton cultivation. By 2004 the Sarghoda tehsil of Bhalwal, where the research for this book was carried out, came to have the highest density of citrus orchards in the district and was often referred to as the ‘California of Pakistan’. The production of citrus was not only more profitable than cotton, and boosted the district as a centre of foreign exchange, but was also significantly less labour intensive. As chapters three and four will illustrate, this allowed wealthy landlords to spend less time supervising agricultural activities and more time in cities such as Sargodha and Lahore, where their children could obtain a better education than in their home villages. This significantly affected the quality of patronage ties between landlords and villagers.

Given the highly unequal distribution of land and access to formal state institutions (which were to a large extent the legacy of the colonial practice of indirect rule through landed notables), the benefits from both the green revolution and the introduction of citrus orchards accrued principally to the landed elites. According to World Bank (2002) estimates, less than half of rural households in Pakistan own any land, and that more than half of rural farm holdings are of less than five acres (ADB 2006: 46) and account for 16 per cent of Pakistan’s total farm area. On the other hand, Malik (2005) reports that in 2000 only 5 per cent of farms were 25 acres or more in size but that they accounted for 38 per cent of all owned land. Moreover statistics for the Punjab from 1976 show that landowners with more than 50 acres of land accounted for more than 18.2 per cent of all land owned. Hussain (1989) and Zaidi (1999) point out that during the green revolution it was principally the large farmers who could get credit to finance the use of new inputs and technologies. These farmers not only possessed substantial collateral in the form of land but also had privileged access to the state distribution of inputs and technologies through their connections with politicians and bureaucrats. On the other hand, tenants and smallholders had to obtain credit through informal institutions, often through landlord farmers, who required them to repay in kind and who often valued their produce at rates that were below market rates. In addition, access to the market in remote areas was often controlled by landlords who owned trucks and marketing outlets, and who could thereby extract a surplus from local smallholders and tenants. The net result was that smallholders derived little benefit from the green revolution and that many even ended up highly indebted and were forced to sell their land. This trend continued well after the initial onset of the green revolution. Hussain (2003) claims that many such smallholders were increasingly being forced to sell their land, and that between 1990 and 2000 as many as 76.5 per cent of the extremely poor and 38.9 per cent of the poor had done so.

Sharecroppers were also negatively affected by the green revolution. Ahmad (1977) reported that prior to the green revolution and to the ‘tractorisation’ that came with it, landlords in the Sargodha village of Sahiwal begged tenants to cultivate as much land as they could in exchange for 50 per cent of the harvest. The reason for this was that many landlords were unable to organise the cultivation of their lands themselves due to the vast number of bullock teams and workers that this would have required. Chakravarti’s (2001) work on Bihar shows that whereas a single bullock team was able to prepare 0.42 acres of land in six hours, a tractor could prepare 25 acres in 20 hours. According to one estimate in Pakistan each tractor introduced in the 1960s displaced between 9 and 12 labourers (Sayeed 1996: 276).

Thus, ‘tractorisation’ meant that landlords could replace a large number of tenants and their bullock teams by a single tractor driver. ‘Tractorisation’ also meant that a lot of land dedicated to the cultivation of fodder for the bullock teams could be turned over to other crops, which dramatically speeded up the turnover of crops in single fields. Lastly, it allowed wealthy landowners to do away with tenants who, under both General Ayub Khan’s and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s land reform programmes, might have decided to claim legal title to the land they cultivated. The result was that between 1960 and 1990 the total area of land in the Punjab cultivated by sharecroppers declined from 37.2 per cent to 14.2 per cent (Zaidi 1999: 42). Finally, in districts like Sargodha, the introduction of citrus orchards in the 1980s also played a significant role in displacing agricultural tenants.

In this way many former smallholders and tenants, as well as village artisans whose goods were to a large extent replaced by mass produced ones, joined the ranks of the mass of ‘unorganised and unprotected workers’ (Breman 1996: 2) bogged down in the transition from agrarian to industrial production. Workers pushed out of agriculture and cottage industries by mechanisation were not formally incorporated into a growing industrial sector. Instead the majority of this work force was employed in a variety of petty trades, services and casual labour in the agricultural sector, the industrial sector and in construction work. Construction work was a particularly important source of employment. The 1998 Government Census claimed that 35.8 per cent of the district’s population was employed in construction, followed by 31 per cent who were employed in agriculture. What the census statistics do not show, as will be described in chapter two, is that the majority of labourers were casual, and moved between agriculture, construction and industry principally located in neighbouring districts.

The Gondals of Bek Sagrana

Prior to canal colonisation, most permanent settlements on the Jech doab were around the banks of the Chenab and Jhelum rivers. Here irrigation was principally carried out through the use of wells (khus) and occasionally through inundation canals. Away from the rivers, scant rainfall made the Jech doab largely unsuitable for settled agriculture despite its rich alluvial soils. These inland areas were sparsely populated by semi-pastoral people (charaghs) who kept livestock and practiced limited single cropping agriculture. Near the banks of the Chenab River in the eastern part of the Jech doab, where the research for this book was carried out, the two dominant semi-pastoralist Jat clans were the Gondals and the Ranjhas.7 Once canal colonisation was underway the colonial administrator Malcolm Darling reported that these pastoralists, or janglis8 as he pejoratively referred to them, were poor cultivators ‘like all primitive folk who have an abundance of land’ (Darling 1934: 14). He claimed that ‘if the jangli is not a good farmer, he is at least a good sportsman. Faction and feud are rife in his villages, and he likes to settle his quarrels in old fashioned ways without recourse to court and police’ (ibid.: 15). Moreover he claimed that ‘once there was hardly a zaildar who was not in the cattle-thieving business, and even now it would be difficult to find anyone of any prominence who had not a relative or two connected with it’ (ibid.). Canal colonisation made perennial agriculture possible and transformed these sparsely populated doabs into the agricultural heartland of the Punjab. Settlers (abadkars) were brought in from other areas of the Punjab and were given titles to canal-irrigated land. Most of these people settled in newly built, planned villages known as chaks. The geometry of these villages was one of squares and straight lines, and reflected the colonial government’s self-professed civilising mission which aimed to create modern and enterprising farmers (Gilmartin 2004). Groups that were native to the region such as the Gondals and the Ranjhas were also given titles of landownership over the newly irrigated land and became settled agriculturalists. However, many of them, including the Gondals, continued to live in the old, unplanned village settlements.

The village of Bek Sagrana is situated to the east of the district towards the banks of the river Chenab. For the village landlords the trip by car to the city of Sargodha took around forty minutes, while the trip to Lahore, along the Korean-built motorway completed in 1997, took about two hours.

For poorer villagers without cars or motorcycles, the trip to Sargodha took an hour and a half on a cramped bus with a deafening musical horn.9

The history of the village was one in which the Gondals repeatedly asserted their dominance against other clans and even against the state. Villagers claimed that Bek Sagrana had once been on the banks of the river situated to the east of the village. With time the shifting course of the river had moved further west, and what was now left of its former course formed a marshland (buddhi). Some villagers claimed that the river had moved west as a result of the prayers of a local village pir whose shrine lay to the east of the village cemetery facing the lowlands. When the river moved, the Gondals allegedly moved with it because of the need for irrigation water. In their absence the Sagranas, a local cultivator lineage (biraderi), had overtaken the village. Subsequently one of the ancestors of all of the present day Gondals in Bek Sagrana, around whom a great deal of legend revolved, decided to resettle in the village and re-conquered it by force and cunning. His descendants boasted about how this ancestor, known as Kala Gondal, or Black Gondal, had called for a gathering with leading Sagranas and had got his men to ambush and kill them as they were making their way to the meeting.10

Much later the great-grandfather of all of the Gondals in Bek Sagrana had murdered a colonial revenue officer (tehsildar) who was alleged to have barged into people’s houses without respect for purdah and to have extorted money from villagers. The killer and some of his accomplices were subsequently tried and hanged. In these stories the Gondals revealed themselves as ruthless, brave and cunning people; qualities deemed essential for effective politicians. They claimed to possess these because of their fundamentally passionate (jezbati) nature which meant that they might act recklessly, and even cruelly, but always out of concern for the interests of kin, friends, allies, and servants.

When I began fieldwork in 2005, many landless villagers still used the lowlands near the former banks of the Chenab river as pastureland for their livestock, but in 2007 Chowdri Abdullah Gondal turned it over to intensive agriculture after forcefully capturing the land from the Makh-dooms.11 Long ago, before the arrival of canal irrigation in the second half of the 19th century, one of the Gondals had donated this land to a Makhdoom saint whose prayers had supposedly made God grant him a son. The formerly politically influential Makhdooms had mainly used the area for hunting wildfowl, but had lost it to Bhutto’s land reforms and to capture by members of the Gondal clan. Elderly villagers recalled how the Makh-dooms had brought Europeans along during their hunting excursions. However, like other erstwhile powerful aristocratic families, the fortunes of the Makhdooms had steadily declined since the 1970s and they were no longer seen hunting. Many powerful landlords had been able to circumvent land reforms by colluding with the local bureaucracy and by evicting tenants who might claim occupancy rights (see Nelson 2011: 146–54), but the Makhdoom’s failed to do so because of their lack of involvement in local politics. Their unwillingness to sully themselves with politics and their small numbers in the area also meant that the far less wealthy but forceful and numerous Gondals of Bek Sagrana were able to overtake them politically and to encroach upon their land. The Gondals justified capturing land they had once donated to the Makhdooms by claiming that the person who now claimed to descend from the Makhdoom saint who had successfully interceded for their ancestor was an interloper and was in fact the descendant of a mere carpenter.