eBook - ePub

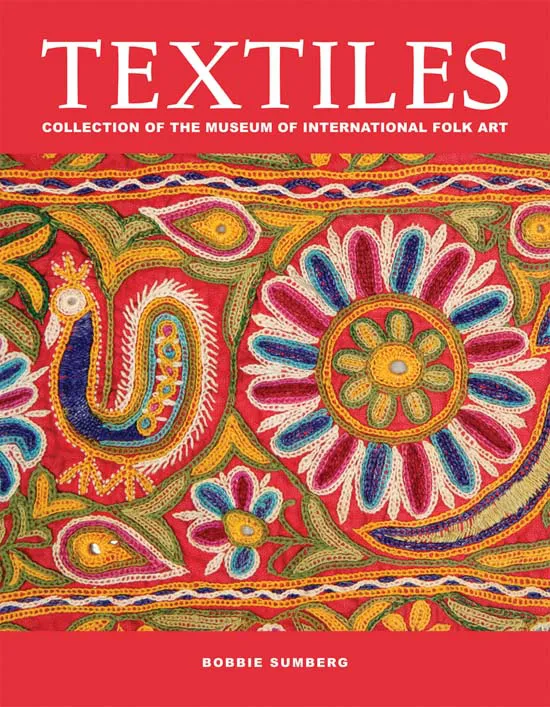

Textiles

About this book

Textiles explores the cultural meaning and exquisite workmanship found in the Museum of International Folk Art’s vast collection that spans centuries and includes pieces from seventy countries around the world. Handcrafted work in beautiful, vivid colors typifies the clothing, hats, robes, bedding, and shoes that represent the lives and passions of the people who created and used them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

Textiles and Dress in the Museum of International Folk Art

The Museum of International Folk Art was founded and given to the state of New Mexico by Florence Dibell Bartlett and opened to the public in 1953. Over the door was engraved the motto “The art of the craftsman is a bond between the peoples of the world.” What better art to demonstrate the universality and particularity of human culture than textile art? When Bartlett gave her personal collection of nearly three thousand pieces to New Mexico, approximately 75 percent of the collection was textiles and items of dress, including garments, hats, shoes, and jewelry.

Many museums collect textiles and dress, but these materials rarely take center stage. The Museum of International Folk Art prioritizes these materials, realizing they are the art of a people in a profound sense, making concrete a culture’s values, aesthetics, and ideas about the cosmos as well as where humans, collectively and individually, fit in the world.

Numerous aspects of history and culture are studied through the production and use of textiles, one of the fascinating characteristics of this material. Gender roles within a family and within a society or culture are usually played out when cloth is made and worn, beginning with the planting of a seed or the raising of an animal. It’s easy to look at a woman spinning or embroidering and think that textile production is exclusively women’s work, but there is so much more to the topic of gender and the production of textiles than that. Each piece in the museum’s collection tells a complex story of the people who made and used it.

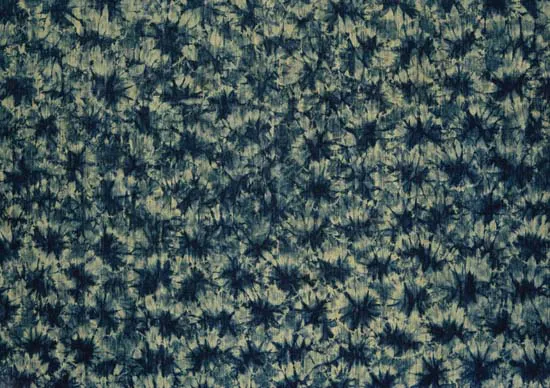

Take, for instance, the tie-dyed cotton cloth from Côte d’Ivoire, below. It was collected in the mid-nineteenth century and provides an excellent example of pre-colonial gender roles related to textile production. In central Côte d’Ivoire, where this cloth might have been made, young men cleared the fields of brush; women then planted the cotton seeds among the other crops. When the cotton was ready, everyone harvested the white or naturally brown bolls. Then it was up to the females of the household to deseed, card, and spin the fiber into yarn and dye it if desired. The yarn was given to a male member of the family to weave into long strips that were sewn together to make a cloth. The size of the cloth was determined by the number and length of strips; cloths for men were bigger than cloths for women. The cloth was then given back to the female head of the household. She decided who received it or if it was to be sold or used for a funeral gift. Men and women worked together and were expected to each do their parts of the process, which were equally important but not the same.[1]

Tie-dyed cotton cloth from Côte d’Ivoire.

Where women are secluded inside the household, the needle arts have often flourished. A needle, a hoop or frame, and a selection of colored threads are all that is needed to create something beautiful that not only demonstrates a woman’s skill but also implies the correctness of her upbringing. Portable embroidery has often constituted a primary social activity for unmarried girls preparing their trousseaus and who are prohibited from contact with the world of men.

Making and embellishing textiles can be a powerful tool of socialization and a reflection of cultural values. The sight of men and women in the Andes spinning with a drop spindle while walking sends a strong message about being productive and not wasting a moment. Young girls learning to weave at a back strap loom in southern Mexico kneel quietly at the loom. They are not only learning a skill but are also learning that to be a woman is to be patient, still, and calm in comportment.

As with gender roles, economic roles are not always so straightforward. There is some—but only limited—truth to the assumption that women produced textiles in the home for use in the home while men labored in commercial workshops making textile products for sale. Like the chef/cook—male/female dichotomy, there is limited truth in this generalization. Female spinners, weavers, and needleworkers have always participated in the market economy, whether working inside or outside of the home. Young New England farm women, who had been weaving cotton cloth at home on contract, were recruited to work in the textile mills in Massachusetts at the start of the Industrial Revolution around 1815.[2] Even when the cultural ideal insists that women are isolated from the marketplace, their earning ability has helped sustain their families. What might be true for wealthy and upper-class women doesn’t necessarily apply to families struggling to keep body and soul together.

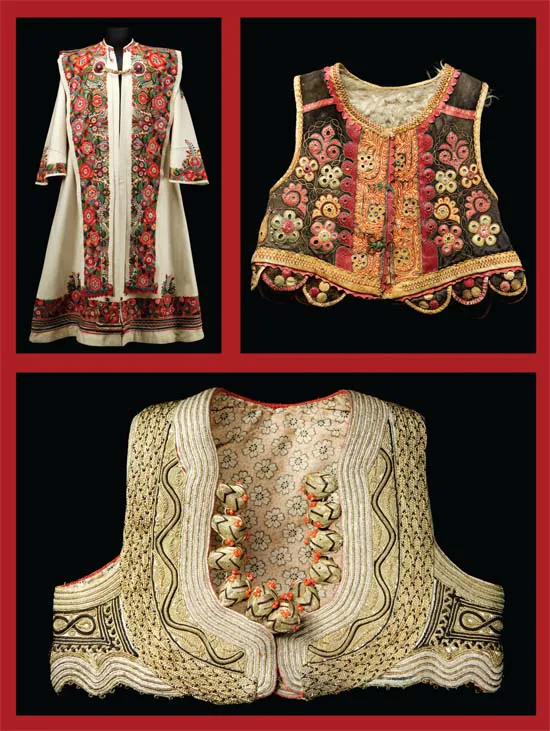

On the other hand, some types of textile work were considered too heavy or difficult for a woman to manage. In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, embroidery on sheepskin, leather, and fulled wool garments, such as those at below, was the domain of professional male embroiderers. These garments were produced entirely in a workshop or professional setting as the materials used required more technical skills and equipment than was found in the home. The irony is that the weight of the clothing worn by women in this part of Europe and the physicality and repetitiveness of the household chores and farming activities women were expected to do ensured that they were very strong!

Embroidery on sheepskin, leather, and fulled wool garments was the domain of male embroiderers.

Different fibers originated in specific parts of the world—cotton in India, Africa, and Mesoamerica; silk in China; wool in the Eastern Mediterranean; and flax for linen in Northern Europe and Egypt. Trad...

Table of contents

- Textiles

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Textiles by Bobbie Sumberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.