1

REFORMERS, EMPLOYERS, AND THE DANGERS OF WORKING-CLASS SMOKING

Once you start, it’s hard to stop.

—kidshealth.org

For children in Chicago, the summer of 1900 began with a busy day of outdoor activities on 15 June, organized for them by the Cook County Anti-Cigarette League. The boy members of the league attended the field day “en masse,” according to a visiting reporter for the New York Times. Just as the fifty-yard dash was set to begin, a bedraggled “street urchin” elbowed his way through the crowd, clenching a lit cigarette between his teeth. Speaking to F. A. Doty, the assistant superintendent of the Cook County Anti-Cigarette League and the referee of the race, he tersely asked, “Wot’s dis?” Doty answered the newcomer with an invitation to participate in the race, telling the boy, “Just to show people why you cannot win because you smoke cigarettes, I will let you enter.” The “stunted” boy apparently accepted the challenge, tossed his cigarette away, and lined up with the other boys of the under-fifteen age group. Surprising everyone, the street urchin “cigarette fiend” won the race and took with him a trophy for his efforts.1 In his own way, the boy challenged the growing movement to curtail cigarette smoking in America, running against then-prevalent assumptions about the ineptitude, dullness, and weakness of smokers. And as this anecdote suggests, attention centered on working-class children as the embodied objects of reform. The Cook County Anti-Cigarette League worried not about adults’ smoking; they focused on boys’ habits.

Throughout the Progressive Era, reformers’ and judges’ assertions that tobacco was a physically, mentally, and morally dangerous drug clashed with working people’s desires to satisfy their addictions, habits, and tastes by smoking cigarettes. Working-class people’s inclinations and actions rested at the heart of antismoking politics during the early twentieth century. In addition, the Progressives who attacked smoking not only wanted to reform working-class behavior, but they also seemed to want to transform their own sensory experiences of urban life. The omnipresent smells and sights of cigarette smoke surely offended and even overwhelmed the respectability of their senses, and antismoking politics provided middle-class men and women with a way to temper the physical presence and environmental influence of the urban working class. One city dweller and “AN ADMIRER OF JUSTICE,” for example, wrote to the New York Times in 1903 to ask whether or not nonsmokers of the big city had “the right to breathe fresh air.” She or he wrote, “Do smokers ever realize the annoyance and positive injury that they cause to those who have that right?” The user of “nasty stinking tobacco” ruined the environment, “defil[ing] himself and the air around him.”2 To improve the smells and sights produced by the working class, reformers focused on modifying the actions and attitudes of boys, the immediate future of upright working-class manhood. The pervasive stench of cigarettes signaled to Progressives the problem of boys’ diminishing health, a real threat to the development of respectable working-class manhood in boys. Could boys who smoked develop the fully formed bodies of adult men? Could they complete the productive labors that were necessary for working-class men in industrial America? Would those boys who smoked habitually descend into crime, depravity, and stupidity? As Progressive reformers’ observations and reactions led them to believe again and again, nicotine fueled the absence of decency, the prevalence of criminality, and the economic failures they associated with working-class culture.

Social and cultural historians’ extensive research into the Progressive Era certainly shows us a great deal regarding middle-class anxieties about working-class culture and morality, but the topic of reformers’ reactions to smoking opens up new dimensions of Progressives’ worries about their own surroundings, views of social class, and what urban “reform” meant.3 Their comments about working-class smokers at the turn of the twentieth century provide us with telling insights regarding their views of urban space, class, and gender, environmental stimuli, personal and public health, and their senses of sight and smell.

This chapter identifies the three fundamentals of antismoking politics at the turn of the twentieth century: (1) Progressives’ concerns about the damaging relationship between smoking and the bad health and behavior of working-class children (specifically boys and adolescents); (2) employers’ and reformers’ concerns about young males’ cigarette smoking as a destroyer of respectable working-class manhood, as tobacco use undermined their health, morals, and abilities and rendered them supposedly imbecilic, unreliable, immoral, and unemployable; and (3) the close relationship between smoking and the very real danger of fire in turn-of-the-twentieth-century urban life, specifically conversations during these years about working-class smokers as deadly sources of factory fires. Overall, the subjects of working-class culture and conduct proved to be central concerns of the men and women who forged antismoking politics in the early twentieth century.

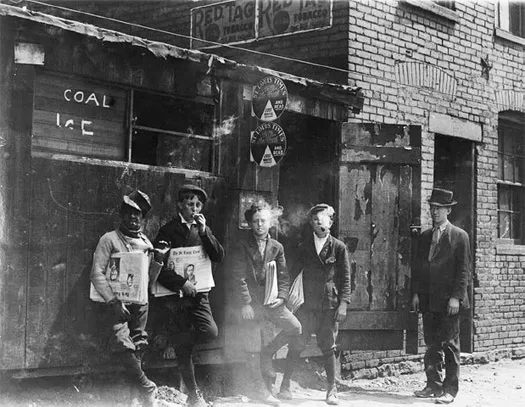

FIGURE 1.1 “Boy with a cigarette during the 1904 Stockyards Strike.” (1904) Chicago Daily News negatives collection, Chicago History Museum, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.ndlpcoop/ichicdn.n001019. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Working-Class Boys and the Making of Antismoking Politics

Victorian moral reformers, Progressives, and other middle-class men and women in the largest American cities at the turn of the twentieth century saw, heard, and smelled much that surely offended their senses and notions of respectability and proper decorum: overflowing garbage bins, noisy immigrant hucksters, dank and overcrowded tenement dwellings, unkempt people, alleys, and streets, unfamiliar languages spoken and shouted in the streets, noisy trains and loud factory whistles, and the odors of unfamiliar cooking.4 Among the many smells and sights of the city, smoking loomed large in middle-class city dwellers’ uneasiness about urban life. Restaurant customers in New York City during the 1910s complained often of the “sickening fumes of tobacco puffed” by legions of cigarette smokers, while members of the Non-Smokers Protective League lamented in 1913 that smoking permeated “almost all public places” and was “generally offensive.”5 In addition to their apparent concerns about the urban environment, middle-class urbanites worried that cigarette smoking was dingy evidence of working-class immorality, physical decay, and mental weakness. In particular, reformers and other urban middle-class residents who condemned cigarettes worried that smoking ruined the potential for respectable manhood in working-class boys and adolescents, as the cigarette purportedly pulled them downward into the physical and moral filth of the city. As the worried automobile magnate Henry Ford proclaimed in his treatise The Case against the Little White Slaver (1916), “the American boy of today” is “the man of tomorrow.” The future of manhood was at stake, he claimed, as young boys turned more and more toward the cigarette.6 In response, Ford hoped to reshape boys’ behaviors and morals with the same strictness that guided the work of his industrial Sociological Department: the institution inside Ford Motor Company plants that policed the personal and professional conduct of adult Ford workers.7

Working-class boy smokers were a ubiquitous presence in cities at the turn of the century, much to the dismay of their worried social betters and elders. For example, in Brooklyn, the school board in 1894 begged local police to arrest boys under the age of sixteen they found smoking, as well as the area sellers who sold them “nauseating and filthy cigarettes.” Brooklyn residents complained of the “customary” practice of high school students to “take possession” of elevated train cars, where they “smoke[d] cigarettes openly and defiantly” during their after-school commutes. Urging the police to act, Brooklyn’s school board members recoiled from what they claimed to be the “alarming extent to which the pernicious and injurious habit of cigarette smoking has spread among schoolboys.” Even when sellers did not provide cigarettes to child consumers, the board complained that boys found individuals who were older than the age of sixteen to buy them.8 Middle-class residents of Los Angeles during the 1890s worried often about the general presence of boy smokers in the city. A visitor from Stockton walked down a main street one evening in 1891 and observed a group of boys smoking on a corner adjacent to a saloon. The visitor moved in closer to watch and listen. “They seemed a good deal animated and were very earnestly discussing some weighty problem of mutual interest,” the observer wrote. The observer spoke to these boys, who were between eight and twelve years old, but was quickly sickened by their rough talk and chain smoking. The hour was 10 p.m. In the dark, the boys smoked foul cigarette stubs they culled from the street. As the observer spoke to them, the boys denounced parental authority, complaining of “apron strings” at home and bragging of the freedom found in the streets. “What will be the future of this republic,” the observer lamented, “if its boys are to grow up robbed of their manhood, brains and morality by this cigarette iniquity?” The observer complained there seemed to be “three sexes”: men, women, and “dudes.” While real men and women were respectable nonsmokers, the “dude” was a lowly working-class male of the city who was “useful” only as “demonstration of the fact that an animal can live on smoke and without brains.”9 Another observer of urban life in Los Angeles noted that if an individual stood at the busy corner of Kearny and Market Streets, that person would witness not just one newspaper boy chain smoking, but “a score of others like him.”10 Working-class boys proved to be major producers of smelly and filthy urban cigarette smoke at the turn of the twentieth century.

As boys smoked their way into the new century, opponents of smoking often framed their views of boy smokers and nonsmokers within a dichotomy of effeminacy versus manliness. William McKeever, a professor of philosophy at the Kansas State Agricultural College, took it upon himself to survey the physical characteristics of 2,500 boy smokers in schools, and what he found suggested that smoking put boys on a definite path to delicateness. He characterized the boy smokers he observed as “sallow,” “squeaky voiced,” “sickly,” and “puny,” pitiable specimens of manhood in formation.11 In contrast, observers assigned the most positive attributes to those boys who were dedicated nonsmokers. Virginia Steel of New York City praised a ten-year-old boy of a Lower East Side neighborhood who organized his own version of an anticigarette club. As the “president” of this apparently “sizeable” club, he set up his office on the basement steps of his tenement building, complete with an overturned ash barrel that he used as a chair. Praising his earnestness and rigorousness (the young president fined club members one and two cents for rule violations such as relapsing into the habit or picking up cigarette butts in the street), Steel lauded the young boy as the “most manly, bright little commander” of his organization.12 In 1916, concerned physician D. H. Kress visited a Detroit school and examined twenty-six boys between the ages of twelve and sixteen. Only two of the boys had never smoked cigarettes, and, according to Kress, they “were, in all respects, the best developed boys in the room.” In his analyses of the boys’ traits, Kress praised the nonsmokers as “the best developed in every way.” They showed the most potential as future men, especially when compared to the sickly and poor-performing boys who smoked. Henry Ford preached to young boys that the competitive world of the 1910s “needs men” who possessed “initiative and vigor”; but the boy who smoked stupidly rendered himself physically, mentally, and morally inadequate for the demands of modern manhood. The famous Detroit Tiger, Ty Cobb, concurred with Ford. “No boy,” he said, “who hopes to be successful in any line can afford to contract a habit that is detrimental to his physical and moral development.”13

FIGURE 1.2 “11:00 A.M. Monday, May 9th, 1910. Newsies at Skeeter’s Branch, Jefferson near Franklin. They were all smoking. Location: St. Louis, Missouri.” Photograph by Lewis Hine. LOT 7480, v. 2, no. 1384 [P&P] LC-H51-1384. Courtesy Library of Congress.

As tobacco smoke saturated the lungs of working-class boys, one observer claimed that cigarettes produced “curious” physical deformities in their fragile young bodies, marked proof of the ruined potential for manhood. A report in the Los Angeles Times claimed that constant cigarette smoking led to the eruption of strange and unsightly spots all over the bodies of two working-class boys, “giving them the appearance of leopards.” The boys’ addictions to nicotine were so great they even had to smoke several cigarettes after retiring to their beds at night. As they were “spotted all over their bodies,” the youths looked less like upright boys on the path to manhood and more like animals.14

Frequent discussions of early deaths due to chronic cigarette smoking underlined observers’ anxieties about the physical vulnerability of boys and adolescents. For instance, William F. Lewis of Brooklyn, New York, died in 1893 as a result of what his doctor believed was “cigarette poisoning.” A pair of friends brought home the limp “Young Lewis,” who appeared to be intoxicated. His parents carried him into the kitchen of their home, where they tried to revive him. They failed. The parents quickly called a local doctor who rushed to the house, but he too failed to bring back their comatose son. He died around 9 p.m. that night. William F. Lewis reportedly smoked heavily, consuming between ten and twelve packages of cigarettes every day, leading the doctor and the aggrieved parents to conclude that his chronic smoking habit surely killed him.15 In Pasadena, California, a twenty-three-year-old male purportedly died as a result of his own “[e]xcessive cigarette smoking.” He smoked as many as fifty cigarettes every day according to the mention of his death in the pages of the Los Angeles Times. As he declined rapidly, the unnamed young man supposedly lived out his last days as an “imbecile” at a hospital. “If a man wishes to commit suicide,” the press opined, “the revolver or strychnine would seem to be preferable to the cigarette.”16 Boys and young adults would never have the chance to become real men when excessive smoking and addiction destroyed their lives.

Concerned public officials viewed smoking not only as a sure path to an early death for young males, but also to working-class criminality. At the 1899 National Conference of Charities and Correction meeting in Cincinnati, George Torrance, who ran the Illinois State Reformatory, lectured on the topic of “The Relation of the Cigarette to Crime.” As he reviewed the records of his charges, he concluded “I am sure cigarettes are destroying and making criminals of more of them than the saloons.” Torrance found that 92 percent of the boys in the Illinois State Reformatory were, in his words, “cigarette fiends” when they were jailed. He estimated that fifty-eight of the sixty-three boys of twelve years of age smoked cigarettes, and seventy-three of the eighty-two boys at the age of fourteen did the same. Of the eighty-two boys who were fifteen years old, he said that seventy-three smoked cigarettes. In his view, smoking did not merely coincide with criminal deeds; rather, cigarettes fueled their wrongdoing.17