![]()

1

Creating Battery Park City

Building a Landmark on Landfill

BETWEEN 1960 AND the present, New York changed from a working-class, industrial city of specialized manufacturers to a global city more singularly cast than ever as a command-and-control center of global capitalism. In the same period, American cities went through equally dramatic social transformations. Places like New York experienced convulsions of population loss as whites fled to the suburbs and African Americans migrated from the South to become majorities or pluralities in many northern cities. New York went through a wave of disinvestment by businesses, banks, and landowners, then experienced a flood of new money as those same players saw the potential to profit from the gentrification of New York as an elite global city. During this period elites vacillated between positive and negative attitudes toward cities like New York, seeing the metropolis first as an industrial economic engine, then as a landscape whose design was physically obsolete, then as a cauldron of racial change and social protest, and still later as a promising site for profitable recolonization.

The fifty-year transformation of industrial Hudson River piers into the luxury enclave of Battery Park City encapsulates this spatial, economic, and political reorganization of New York City so well that it provides an ideal perspective on the successive visions for restructuring New York that elites have implemented. More specifically, earlier work has shown that the physical designs that elite real estate developers and city builders choose for large construction projects like Battery Park City are uniquely positioned to tell the story of this complex urban transformation.1 In fact, projects such as the master plans for Battery Park City are leading indicators of the shape of cities to come, offering some of the earliest evidence of elites’ plans, not just for a single project, but for the city at large.

New York’s public spaces went through four distinct stages in the last half of the twentieth century. This chapter explores them by examining the succession of master plans for Battery Park City, explaining the history that gave Battery Park City its physical shape and social configuration and demonstrating why contests over the shape of Battery Park City reveal changes in the whole city, not just one community.

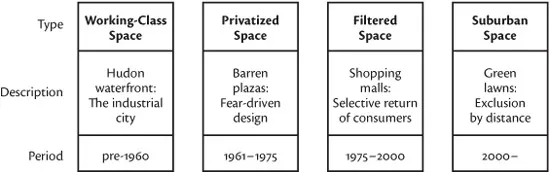

Public space consists of parks, plazas, malls, sidewalks, and street corners, all the generally accessible parts of the city where one is likely to meet and interact with strangers.2 Each of the four stages of New York City’s history over the latter twentieth century has been characterized by a particular type of public space. Through the 1950s, New York was a city of working-class spaces like the piers. By the early to mid-1960s, elites’ reaction to civil rights struggles, population decline, increases in crime, and their own insecurities was to create privatized spaces. These included designs for development projects and public spaces that would barricade them from the larger public with fences, walls, elevated platforms, and locked gates. In the third stage, elites sought to selectively recolonize the city through filtered spaces such as shopping malls and enclosed atria that would be attractive to an upper middle class that developers sought to draw back into the city, but would keep out working-class and poor people and people of color. Finally, consistent with the ultimate shape of elites’ gentrifying program of urban restructuring, under its last master plan Battery Park City developed the strategies of suburban spaces, creating lush environments for upper-income residents and employees and using distance to segregate disadvantaged people from those resources.

Typology of urban space. Typical spaces constructed by structural speculators in each of the periods shown above shared key traits.

A History of Exclusion

In the context of discussing Battery Park City, the word exclusion has two overlapping meanings. First, it refers to the decision to price housing in the neighborhood at luxury rates so that lower- and middle- income people generally cannot live there. Second, according to some critiques, it refers to exclusion through the neighborhood’s design: planners have surrounded the neighborhood with physical barriers—a difficult-to-cross highway, guard booths, hard-to-find entrances—that have the effect, on the ground, of keeping away people who are not wealthy, either because those obstacles make it difficult to enter the neighborhood or because stylistic choices make people of modest or normal means feel they are not supposed to be there. Critics argue that these designs also cocoon residents in attractive but underused outdoor spaces that lack a broad public character, leaving residents without opportunities for democratic public interaction.

Architects distinguish between a “program,” which describes the functions that a client wants a building to accommodate, and a design, which is the form the building takes while serving those functions. Thus the “citadel critique”—that Battery Park City was intended to function as a refuge for rich people—describes what I call programmatic exclusion, while the claim that the neighborhood has been designed to use physical barriers, like the daunting West Side Highway, guard booths, or hidden entrances, to keep out the rest of us describes what I call design exclusion.

The social privilege that elites sought to reinforce in Battery Park City produced the neighborhood’s programmatic exclusion, while a shifting social context and a long history of failed master plans eventually relocated the focus of design-based exclusion efforts beyond the boundaries of the neighborhood to New York’s low-income communities of color. The ultimate design, as modified through generations of master plans, proves critical to understanding the community that came to live there.

1962: The Plan for a Working Port

Before becoming the contested site for a major development project, the area that would be Battery Park City had been a working port almost since the city’s founding by the Dutch.3 In the mid – twentieth century, the piers needed to be repaired, and this prompted the original plan for the Battery Park City area.

The city’s Department of Marine and Aviation, which oversaw the piers, proposed maintaining the area’s role as a working port. Warehouse and trucking facilities would operate at ground level, with high-rises surrounded by elevated plazas built above. The project would include 4,500 apartments, a hotel, and office space.4 Though this plan made room for white-collar workers, they shared priority with working-class longshoremen, sailors, and Teamsters.

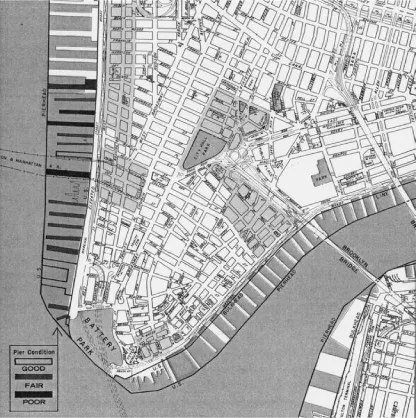

Conditions before the construction of Battery Park City shaped the neighborhood, including pierhead and bulkhead lines, Hudson River train tunnels, and the condition of existing piers. (Wallace K. Harrison, “‘Battery Park City’: New Living Space for New York, a Proposal for Creating a Site for Residential and Business Facilities in Lower Manhattan, 1966,” Wallace K. Harrison Archives, Avery Library, Columbia University)

The 1962 plan was the last acknowledgment in planning documents for Lower Manhattan of the city’s working-class base. In that era, New York had more manufacturing jobs than Philadelphia, Detroit, Los Angeles, and Boston combined.5 In the decades after the end of the Second World War, 25 to 30 percent of working New Yorkers were unionized, with over a million workers paying union dues. The city’s largest union, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, had nearly two hundred thousand members into the 1960s. Nonetheless, new economic and real estate development in New York was not directed toward the city’s growth as an industrial center. After the plan by the Department of Marine and Aviation, business executives, real estate developers, and government agencies drawing up plans for Battery Park City never again considered warehouses, ferries, cargo ships, or commercial produce markets in their plans. For this reason, the sociologist Sharon Zukin calls this era the “threshold period,” when industry began its move to suburban locations.6 Within a year, decision makers’ plans for the area that would become Battery Park City would definitively shift their focus to the white-collar financial sector of the city.

The 1962 plan made little headway, but it introduced several important ideas that would ultimately shape Battery Park City. It was the first to recommend a mix of office and residential uses for the space. It signaled to others the city’s recognition that significant space near Lower Manhattan needed to be refurbished and suggested to developers that it might be up for grabs. For some time elites’ plans had recommended uprooting New York’s working-class, specialized industrial base and replacing it with a city serving the immediate needs of financial firms.7 Downtown decision makers soon proposed transforming the waterfront from blue-collar to white-collar uses. Many writers have described Battery Park City, as it was ultimately built, as the product of global capitalism. But rarely do we see how such a global force shapes a specific, local area. The first white-collar plan for Battery Park City presents the individuals whose actions interpreted abstract and global social changes—in this case, the rise of global capitalism—in the shaping of concrete and local spaces like Battery Park City.

1963: Chase Manhattan Bank and David Rockefeller’s Plan

Manhattan has two central business districts: the Financial District, on the site of the original European settlement on Manhattan at the southern tip of the island, and Midtown, three miles north in a part of the city organized by the well-known grid of numbered streets and avenues.8 For decades, Downtown’s elites had worried that corporate headquarters would continue to abandon Downtown for Midtown because of the competitive disadvantage of the Financial District’s restricted space and smaller lots. The Battery Park City project was proposed in the early 1960s by David Rockefeller, then vice-chair of Chase Manhattan Bank, to retain and attract corporations to Lower Manhattan. Rockefeller had recently led Chase in their decision to build a new headquarters in the smaller, more crowded and economically faltering Downtown rather than in Midtown. First National City Bank, Chase’s major competitor, had moved to Midtown just four years before the new Chase building was dedicated, and Chase’s considerable investment motivated the bank to promote a general revitalization of Downtown.9 At the suggestion of the city builder Robert Moses, Rockefeller founded the Downtown – Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA) in 1958 to “speak on behalf of the downtown financial community and offer a cohesive plan for the physical redevelopment of Wall Street.”10

Rockefeller was particularly well suited to lead such an effort. He was the youngest of the six children of John D. Rockefeller Jr., who, as heirs to the fortune of their robber baron grandfather, had had to develop public identities in relation to their private wealth. David’s brother Nelson had gone into politics; David instead built a more stable network of power in business, becoming chief executive at Chase Manhattan Bank and developing extensive international contacts among businessmen, dictators, and politicians.11 (The head of Goldman Sachs once complained, “David’s always got an Emperor or a Shah or some other damn person over here, and is always giving him lunches. If I went to all the lunches he gives for people like that, I’d never get any work done.”)12 As with the DLMA, Rockefeller typically promoted his goals by leading a larger coalition of like-minded businessmen.13 The DLMA was not the only organization to propose renovating Downtown. But given his enthusiasm for such projects and the influence that accompanied the power and wealth of Chase and his family’s fortune, it is not surprising his organization’s plans set Battery Park City in motion.

Observers of global cities argue that global capitalism produces citadels as protected enclaves for capitalism’s elite, but it has not been clear how two distinct systems such as global capitalism and, for instance, New York City urban planning ever actually connected to each other. David Rockefeller was a universal joint that connected the former to the latter. He was proudly globalist in outlook, writing, “Some even believe we are part of a secret cabal … characterizing my family and me as ‘internationalists’ and of conspiring with others around the world to build a more integrated global political and economic structure. . . . If that’s the charge, I stand guilty, and I am proud of it.” But his interest in the planet was not altruistic; his goal was to increase U.S. control of the international economy and of resources in other countries. His interest in Latin America led him to criticize a Kennedy-era proposal, for instance, “for not insisting strongly enough that the Latin nations promote the expansion of private US capital.”14 He was an early backer of the U.S. invasion of Vietnam, and he provided loans to help the U.S.-allied apartheid government of South Africa after other nations withdrew investments to protest the 1960 Sharpeville massacre. While it is important to avoid the trap of attributing too much influence to a single, publicly visible figure, Rockefeller fit the mold of a global capitalist and had the influence to lead elected and business officials to seriously consider plans to build Battery Park City. He was one of many people involved who illustrated how, exactly, globalization constructed local citadels.

The DLMA immediately issued a report in 1958 calling for improved infrastructure, changes in land use, major building projects, and demolition of the Hudson and East River piers to make room for the needs of the DLMA’s financial industry members.15 The DLMA’s 1963 report was the first to propose Battery Park City in recognizable form, as a mile-long landfill project for luxury high-rises. The plan for Battery Park City did not arise in isolation, however. It was one element of the overall plan of the DLMA and Downtown interests to enlarge and modernize Lower Manhattan by providing much more land for office and apartment construction. Thus Battery Park City was one of eleven major improvement projects recommended in the 1963 report, and the World Trade Center was another. The DLMA had actually already proposed, in 1960, both a World Center of Trade (or World Trade Mart) and a cluster of high-rise housing near the old Battery at the southern tip of the island, but had sketched them out on the East River, on the other side of Manhattan.16 The Port Authority (which answered to New York and New Jersey’s governors) had agreed to the building of the World Trade Center, but at New Jersey’s insistence it stipulated that the site be moved from the East River to the Hudson River, above the terminus of the New Jersey – New York commuter train line that the Port Authority had just taken over. When the Trade Center moved, Battery Park City moved with it to the piers New York had already been planning to redevelop.17

The ambitiousness of the DLMA’s plans—reconfiguring all of Lower Manhattan in an effort to “modernize” it—was consistent with the scale of city building in that era. New York’s notorious power broker Robert Moses, who was building highways, parks, and high-rise housing and was bulldozing thousands of homes to do it, approved of the DLMA’s vision. He sought support for his own Downtown project, an expressway across Lower Manhattan that would have cut through SoHo, Chinatown, and Little Italy, with these words: “Not to be overlooked in examining the benefits of the Expressway is the tremendous stimulus it will provide to the program of the Downtown – Lower Manhattan Association. … This group of distinguished downtown leaders, headed by David Rockefeller, is assiduously tacking a ...