![]()

1

BRANDING CONSUMER CITIZENS

GENDER AND THE EMERGENCE OF BRAND CULTURE

Download our free self-esteem tools!

—Dove website

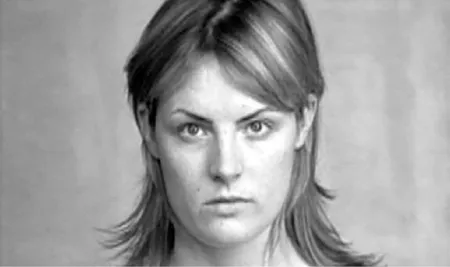

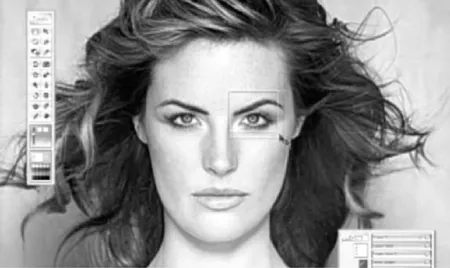

In October 2006, the promotion company Ogilvy & Mather created “Evolution,” the first in a series of viral videos for Dove soap.1 The ninety-five-second video advertisement depicts an ordinary woman going through elaborate technological processes to become a beautiful model: through time-lapse photography, we watch the woman having makeup applied and her hair curled and dried. The video then cuts to a computer screen, where the woman’s face is airbrushed to make her cheeks and brow smooth, as well as Photoshopped and manipulated: her neck is elongated, her eyes widened, her nose narrowed.

The video is not subtle; it is a blatant critique of the artificiality and unreality of the women produced by the beauty industry. The concluding tagline reads, “No wonder our perception of beauty is distorted. Take part in the Dove Real Beauty Workshops for Girls.”

According to its website, the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty is “a global effort that is intended to serve as a starting point for societal change and act as a catalyst for widening the definition and discussion of beauty.”2 It is one of a growing number of brand efforts that harness the politicized rhetoric of commodity activism. In short, the “Evolution” video makes a plea to consumers to act politically through consumer behavior—in this case, by establishing a very particular type of brand loyalty with Dove products. The company suggested that by purchasing Dove products, and by inserting themselves into this ad campaign, consumers could “own” their personalized message. Rather than the traditional advertising route of buying advertising slots to distribute the video, Dove posted it on YouTube. It quickly became a viral hit, with millions of viewers sharing the video through email and other media-sharing websites.3 Well received outside of advertising, the video won the Viral and Film categories Grand Prix awards at Cannes Lions 2007.

The “before” image of the Dove “Evolution” ad.

With its self-esteem workshops and bold claim that the campaign can be a “starting point for societal change,” the Dove Campaign for Real Beauty is a current example of commodity activism, one of the ways that advertisers and marketers use brands as lucrative avenues for social activism, and social movements in turn use brands as launch points for specific political issues.4 Commodity activism reshapes and reimagines forms and practices of social (and political) activism into marketable commodities and takes specific form within brand culture.5 It has a heightened presence in today’s neoliberal era, which has seen an incorporation of politics and anticonsumption practices into the logics of merchandising, the ubiquity of celebrity activists and philanthropists, and yet a new configuration of the consumer citizen. Like other forms of social or political activism, commodity activism hinges on a central goal of empowerment. However, despite the social-change rhetoric framing much commodity activism, the empowerment aimed for is most often personal and individual, not one that emerges from collective struggle or civic participation. In this context of brand culture, the individual is a flexible commodity that can be packaged, made, and remade—a commodity that gains value through self-empowerment.

The “after” image of the Dove “Evolution” ad.

Commodity activism takes shape within the logic and language of branding and is a compelling example of the ambivalence that structures brand culture. This kind of activism not only illustrates the contradictions, contingencies, and paradoxes shaping consumer capital today but also exemplifies the connections—sometimes smooth, sometimes contradictory—between merchandising, political ideologies, and consumer citizenship. The Dove campaign represents a historical moment of transition, Joseé Johnston notes, characteristic of the kind of change unique to contemporary commodity activism: “While formal opportunities for citizenship seemed to retract under neoliberalism, opportunities for a lifestyle politics of consumption rose correspondingly.”6 Dove offers a productive lens not only into this rise but also into the concurrent retraction of social services and collective organizing that are characteristic of the current political economy—in other words, into the contemporary neoliberal world where anyone, apparently, can become a successful entrepreneur, can find and express their authentic self, or can be empowered by the seemingly endless possibilities in digital spaces, and yet where the divide between rich and poor continues to grow. In this context, personal empowerment is ostensibly realized through occupying the subject position of the consumer citizen. According to today’s market logic, consumer citizens can satisfy their individual needs through consumer behavior, thus rendering unnecessary the collective responsibilities that have historically been expected from a citizen.7

Dove is merely one example of an increasingly visible kind of commodity activism in the 21st-century brand culture of the US. Certainly, commodity activism did not appear as a direct result of late 20th-century and early 21st-century neoliberal capitalism. Boycotts, such as those in US civil rights movements for equal African American and white consumer rights, Ralph Nader’s consumer advocacy of the 1960s and 1970s, and the emergence of “ethical consumption” in the 1980s, could be accurately called commodity activism.8 In this chapter, I am interested in tracing the relationships these histories have with contemporary definitions of branded activism.

Contemporary forms of commodity activism are often animated by and experienced through brand platforms. Individual consumers demonstrate their politics by purchasing particular brands over others in a competitive marketplace; specific brands are attached to political aims and goals, such as Starbucks coffee and fair trade, or a RED Gap T-shirt and fighting AIDS in Africa. Contemporary commodity activism positions political action as part of a competitive, capitalist brand culture, so that activism is reframed as realizable through supporting particular brands; activism is as easy as a swipe of your credit card. This competitive context for commodity activism, like the context for brands themselves, means that some forms of activism have a heightened visibility while others are rendered invisible. That is, if activism is retooled as a kind of product that either prospers or fails through capitalism’s circuits of exchange, then some kinds of activism are more “brandable” than others. The vocabulary of brand culture is mapped onto social and political activism, so that the forces that propel and legitimate competition among and between brands also do the same kind of cultural work for activism.

Within these dynamics, the brand is the legitimating factor, no matter what the specific political ideology or practice in question. That is, the flexibility of branding enables a given brand to absorb politics, but that flexibility is subject to the market. In the case of Dove, the politics embraced by the company involves gender and self-esteem. To be blunt, girls’ self-esteem is hot: there are best-selling books and Hollywood movies about “mean girls,” eating disorders continue to be a problem for young girls (and one that is not confined to the white middle class), popular culture is constantly regaling the latest efforts by female celebrities to conform to an idealized feminine body. Girls’ self-esteem in the early 21st century, in other words, is remarkably brandable.

While I argue in this book for a broad definition of brand cultures, experienced through expansive brand logics and strategies, in this chapter I examine broad ramifications through a focus on one specific brand. Dove, owned by the global personal care company Unilever, is currently the world’s top-selling cleansing bar.9 In the 1990s, Dove began to expand its product line beyond soap, and the line now includes shampoos, conditioners, deodorant, and other cleansing products for women. Dove began to attract global attention in 2004 for its marketing and branding; the company hired Ogilvy & Mather in that year to develop a series of ads portraying the “real beauty” of ordinary women. In 2006, Dove started the Dove Self-Esteem Fund, which purports to “be an agent of change” through educating girls and women on a “wider definition of beauty.”10 These brand campaigns have received much public attention for their efforts to intervene in advertising’s standard representations of femininity, in which models are primarily white, thin, and blond, and thus exclude the majority of the world’s citizens. As a challenge to this idealized image, Dove initially distributed ads that featured “real” women of different sizes and ethnicities, with slogans such as “tested on real curves.” It is this reimagined brand identity of Dove, updated and experienced in 2010 as a multimedia, interactive campaign including videos, blogs, online resources for girls and women, and international workshops on self-esteem, that is the specific focus of this chapter, where I will trace the trajectory from selling products to selling identities to selling culture through an analysis of “real beauty” as well as Dove campaigns from two earlier eras.

Commodity Activism in Three Moments of Economic Transition

Commodity feminism, where feminist ideals such as self-empowerment and agency are attached to products as a selling point, is one specific element of commodity activism, which in turn is one part of the larger story of the historical emergence of brand culture. As an example of commodity feminism, or what some have called “power femininity,”11 the Real Beauty campaign brings into relief a debate over the relationship between gender and consumer culture that has been taking place, in both national arguments and everyday interactions, since at least the 19th century. The question, in some ways, is simple: Have women “been empowered by access to the goods, sites, spectacles, and services associated with mass consumption”?12 Writing about “power femininity” in ads, Michele Lazar characterizes this “knowledge as power” trope within contemporary marketing as an element of consumer-based empowerment, where brands like Dove offer educational services to consumers so that they can develop skills to become their own experts on self-esteem. The development of these skills is positioned, in turn, as a conduit to self-empowerment.13 The Dove Real Beauty campaign, through its workshops and media resources, claims to enable girls to become confident and self-reliant through healthy self-esteem.

As Victoria de Grazia, Susan Bordo, Lynn Spigel, and many others have pointed out, there are a variety of points of entry into debates about consumer empowerment for women, ranging from historical analyses of consumer culture’s empowering expansion of middle-class women’s social and institutional boundaries to examinations of consumer culture representations of women and the “female” audience.14 My examination of the Dove Real Beauty campaign approaches it as one of many contemporary examples of an advanced capitalist strategy that restages corporate and managerial practices (such as those of Unilever) into political, and in this case feminist, and social contexts. In the relentless search for profit, this retooled capitalism is built upon a restructuring of traditional identities (in this case, of gender) and social relations (in this case, between consumer and producer). Needless to say, some shifts in identity and relationships are easier to brand than others; wanting to improve girls’ self-esteem is not a controversial political platform (unlike, say, immigration rights or same-sex marriage). In addition, the issue has a vast market—from self-help books to reality television shows to pedagogical initiatives—in the US that supports Dove’s particular commodity activism. Nevertheless, it is worth reconsidering the logic of such brand campaigns. Why does a company driven by profit care about social issues? How did we get here? What is the historical context for this neoliberal recontextualization?

As much as marketers will tell you otherwise, the market itself is only part of the story. So when considering habits of consumption within advanced capitalism, and what that tells us about our identities and our relationships, we also must consider the equally important, but more abstract, notion of what constitutes a commodity in the first place. Is racial or gender identity a commodity? Can the pursuit of social justice be commodified? If the answer to these and similar questions is yes, what does that mean for individuals, institutions, and politics? What does it mean in terms of how cultural values are changing? Exploring the ramifications of commodification means considering what it means to be a social activist in an environment that above all else values self-empowerment and entrepreneurial individualism.

In order to address such questions, I examine commodity activism at three historical moments in US culture. These historical moments represent industry-defined transitions in relations of production, the creation of markets, and consumer culture. Crucial to each are technological shifts that are created, supported, and enabled by specific understandings of consumer capital as well as shifting notions of political and cultural subjectivity.

• First, I examine mass consumption within Fordist capitalism of the mid-20th century. In this era both broadcast media (such as film, broadcast television, and radio) and political subjectivity were often formulated collectively (from membership in one’s social class or the imagined homogeneous, relatively undifferentiated audience).

• Second, I explore niche marketing and post-Fordist (or late) capitalism in the late 20th century. Here, new information technologies and narrowcast media (such as cable television and the Internet) fragment the formerly broad, mass audience into groups of more diverse communities. These audiences are differentiated by specific racialized or gendered groups (as well as other identity groups), and their “identities” are imagined (and marketed to) accordingly.

• Third, I examine individuated marketing and neoliberal labor practices of the late 20th century and early 21st century. These include immaterial labor, which is animated by the digital economy, and the blurring of consumer and producer identities (as with “viral” ads, user-generated online content, and brand culture), so that the individual cultural entrepreneur is celebrated as one who populates a radically “free” market.

To be clear, charting three economies is not an indication that one cultural and economic context ends as another begins; rather, there remains overlap between all three economies, and they both detract from and inherit legacies of their predecessors. These historical moments map transitions—some advancements, some retrenchments—in a longer history of culture, economy, and the construction of subjectivity within the capitalist episteme. It is often, as de Grazia reminds us, in the moments of transition—such as those I have outlined—that tensions around meanings of identities become especially visible.15

Getting “Creamed”: Mid-20th-Century Mass Audiences and the Unified Subject

Interpreting advertisements targeted to women offers insight to the various ways in which gender and national identity intersect in different ways at different historical stages. Beauty and hygiene products have long been connected, by marketers and consumers alike, to broader relationships between personal identity, dominant racial and gender formations, and the nation. Soap, for instance, has historically been a rich vehicle for the notion of consumption as a kind of civic duty. Even in the 19th century, as Anne McClintock has shown, soap (and other commodities) stood in for values that traversed the cleanliness of the physical body into the “cleanliness” of the social body. Commodities were seen to represent cultural and social value, and through visual representations in advertising, they affirmed racial and gender hierarchies.16 In particular, as McClintock demonstrates, in the colonial building of empire of the 19th century, “Soap flourished not only because it created and filled a spectacular gap in the domestic market but also because, as a cheap and portable domestic commodity, it could persuasively mediate the Victorian poetics of racial hygiene and imperial progress.”17

Into the 20th century, feminine beauty products continued to be associated with national identity and rhetorics of American “progress.”18 Yet at the same time, the cultivation of a female consumer base authorized new social positions for women that disrupted traditional gender hierarchies in US society. Historian Kathy Peiss, for example, challenges a reductionist account of cosmetics as merely “masks” for apparent feminine shortcomings—whether these masks are imposed by patriarchal society (women needing artifice to compete) or by racist culture (“whiteners” and other means to affirm racist hierarchies among women). Rather, Peiss argues that women’s consumption of cosmetics needs to be understood within a broader context of struggles between consumer conformity and female empowerment. While surely the marketing of cosmetics contributed to the commodification of gendered identity (where types of women are branded as products), it also, as Peiss argues, destabilized traditional gendered hierarchies based on noti...