![]()

1

Roots and the Perils of African American Television Drama in a Global World

Prior to the runaway worldwide popularity of the 1977 miniseries Roots, few television series featuring African Americans circulated internationally, and none had sufficient success in foreign sales to catch the eyes of program merchants. Amos ’n’ Andy (1951–1953) appeared in the United Kingdom, Australia, Guam, and Nigeria in the 1950s and 1960s, and a smattering of African American situation comedies of the 1970s sold sporadically, including Good Times (1974–1979) and Sanford and Son (1972–1977), but none of these series did much to change the dominant perception at the time that few African American television series could appeal to white American viewers, much less viewers abroad.

Roots likewise faced a good deal of resistance among industry insiders, and its global popularity not only defied conventional wisdom at the time, but also paved the way for a slew of miniseries on the world markets. In fact, the success of Roots abroad helped solidify a business model for funding miniseries production that relied heavily on international sales. However, prevalent industry lore at the time tended to deflect attention from the distinctly African American elements of Roots in explaining the miniseries’ success abroad, focusing instead on historical themes and supposedly universal family themes. Consequently, the majority of miniseries that followed in Roots’ wake told stories about white American and European history.

Roots grew out of a moment of racial ferment in the United States. The early 1970s had witnessed the growing economic, political, and cultural clout of diverse African American groups, including black nationalists, black separatists, and the Black Power movement. Roots picked up on and recirculated a range of African American discourses, chief among them the extreme psychological, cultural, and communal ruptures that slavery caused; the importance of reconnecting with the past and with Africa; and the historical and contemporary culpability of whites and white power structures. At the same time, the miniseries retained more conservative discourses of racial integration, the American melting pot, and the availability of the American Dream; simply the alteration in the subtitle between Alex Haley’s book and David Wolper’s television series—from Roots: The Saga of an American Family to Roots: The Triumph of an American Family—reflected this conservatism for numerous contemporary observers.

Many progressive and radical discourses underlay the popularity of Roots abroad and the institutional labors that the miniseries performed, even in predominantly white European markets. At the same time, while African American discourses obviously resonated with audiences and programmers in nonwhite and non-Western markets, programmers in several Western European markets seem to have used the miniseries as a way to begin to exorcise white guilt for the treatment of domestic minorities. In nearby Eastern Europe, the details of African American history intersected with the history of imperial exploitation at the hands of Western powers, as well as the political interests of the socialist parties. In other words, in Western Europe, Roots’ representations of racial exploitation, guilt, and overcoming fit the institutional needs of public broadcasters, while for Eastern European state broadcasters, slavery served as a metonym for capitalist exploitation in general.

The specific institutional, economic, and cultural forces that shaped the worldwide circulation of Roots produced African American television portrayals rooted in historical settings and storylines and roles related to slavery. The majority of miniseries that followed in Roots’ wake only tangentially included African Americans, and those that did were set in the Civil War, in large part because the economics of production required sales to Western European broadcasters to recoup costs. The exception was the sequel to Roots, Roots: The Next Generations, which is notable in its own right for telling the story of African American political struggle through the civil rights movements of the 1960s, but whose popularity was explained away by the popularity of the original and consequently did not influence wider televisual portrayals.

Roots and the Struggle for International Distribution

So many myths have sprung up around the Roots miniseries and its journey from concept to network blockbuster that it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction. One of the most popular myths is that its success took everyone involved with the project by surprise. The ABC programmer Fred Silverman, reportedly worried that the miniseries would be a ratings bust and destroy the network’s January sweeps numbers, presciently decided to schedule the episodes back-to-back in order to minimize the potential ratings damage for ABC. The result was a relentless and crescendoing buzz among viewers that culminated in the largest single audience for any fictional television program at the time, when 71 percent of the viewing public tuned in to watch the final episode, or about thirty-six million viewers (Warner Brothers, n.d., a). ABC had sold advertising slots based on an expected 35 percent audience share, so the miniseries obviously did exceed the network’s expectations by a large margin (Quinlan, 1979). Still, Silverman had doubled both the length and the budget of the miniseries when he arrived at ABC in 1975, suggesting that he might have had more confidence in the series’ performance than is popularly assumed (Wolper, 2003).

Regardless of the precise facts, however, it seems clear that both trepidation and high hopes circulated around the Roots project from the beginning. Its budget surpassed that of even the most expensive television genre of the time, the movie of the week, topping $500,000 per hour versus an average $425,000 per hour for television movies (Russell, 1975). Nevertheless, the producer David L. Wolper went more than $1 million in debt to help finance the project, a debt that surely contributed to his decision to sell his production company to Warner Brothers in early 1976 for $1.5 million (Wolper, 2003). Always the astute businessman, however, Wolper retained his domestic and international syndication rights for Roots in the deal, demonstrating his confidence in the profitability of the program.

The uncertainty about whether Roots would become the hit television program that its producer was sure it would infiltrated the international markets as well, where Wolper turned, rather unsuccessfully, to help finance his increasingly ambitious and expensive undertaking. Wolper pursued both direct sales to foreign buyers and arrangements with well-known international syndicators in his efforts to garner sales revenues up front. Channel 7 in Sydney, Australia, bid early for the project, and feverishly worked to retain its purchase rights after Wolper sold his company to Warner Brothers, which had an exclusive distribution contract with its rival Australian network, Channel 10 (Kinging, 1976). Apparently, both commercial broadcasters had high hopes for the miniseries. Meanwhile, half a world away, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) had similar interests in acquiring the series, and requested the opportunity to preview the rough cuts of the first few episodes in 1976 (Somerset-Ward, 1976). Rounding out the main English-speaking markets at the time, Canadian buyers were split on acquiring Roots. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) declined to purchase the miniseries in 1976, ostensibly due to Canadian Content (CanCon) regulations, which required that 60 percent of prime-time programming come from Canadian producers. According to Merv Stone (1976), the manager of program purchasing for the CBC, a twelve-hour series would have been too difficult to schedule effectively while respecting CanCon regulations. Regardless of such difficulties, however, the CBC managed to import many television dramas from the United States at the time that comprised far more than twelve hours of programming per season. More likely, the CBC wished to pass on the series and simply used CanCon regulations as an excuse for turning the series down. By contrast, Simcom International, a Canadian distributor, believed that the series would sell well to commercial broadcasters in Canada, fetching perhaps more than $100,000 (Simpson, 1976).

Outside English-speaking markets, Wolper turned to U.S. distributors with experience in international syndication for help selling the series, but to no avail. David Raphel, president of Twentieth Century Fox International Corporation, wrote to Wolper that although the script was “extremely interesting,” he did “not believe that much [could] be done with it overseas” (Raphel, 1976). Wolper got a similar response from United Artists when he approached them about an international syndication deal. Desperate, Wolper sought to edit the first three hours of the miniseries and release it in theaters abroad as a feature film, even promising Twentieth Century Fox that he could “add things that you may want for the feature (more violence, more sex, et cetera)” (Wolper, 1976). However, international distributors passed on this project as well.

Wolper’s perception that the miniseries might perform better as a theatrical film and his offer to make the story more spectacular reiterate the perceived dailiness of television in comparison with popular film, as well as the impact those perceptions can have on black representations. In 1970s Hollywood, black male bodies became synonymous with sex and violence due to the popularity of blaxploitation films, while at the networks, even realistic dramas such as Roots only nominally included such portrayals. Thus, some of the main ways blackness has come to be portrayed in globally distributed Hollywood action films are understood as inherently at odds with industry-wide perceptions of the television viewing experience, which tends to work against the production and circulation of African American television dramas.

Roots’ unprecedented success in the United States almost guaranteed that foreign broadcasters, who typically show strong interest in the most popular U.S. television series, would pick up the miniseries. However, nothing could have prepared either Wolper or Warner Brothers for its phenomenal performance abroad. In Australia it achieved audience ratings that were nearly equivalent to those in the United States, averaging a 66 share over eight nights (“Roots a Hit,” 1977). In West Germany it posted similar ratings, garnering a 49 share on its first night and a 55 share on its second (Seeger, 1978). One West German network spokesperson exclaimed, “We never expected it to be the biggest hit of all times” (“West Germans Tune In,” 1978). In Italy, too, Roots brought in a record number of viewers for an imported series, attracting nearly twenty million viewers per night (“Roots Sets TV Records,” 1978). Outside Europe, the Japanese broadcaster Asahi TV claimed to be “delighted” with the miniseries, which performed especially well with young men and reportedly sparked a nationwide fascination with rediscovering one’s ancestors (Chapman, 1977). These are just a handful of examples that found their way into U.S. newspapers. By the end of the decade, Warner Brothers (n.d., a) promotional materials listed forty-nine territories that had broadcast the miniseries, and rights to the sequel Roots: The Next Generations, which performed less well than the original in the United States, were sold to eighty-six countries, according to internal Warner Brothers (1994) fiscal reports.

Despite these impressive statistics, awareness of the worldwide popularity of the miniseries seems to have dawned slowly on Warner Brothers executives. Of course, reconstructing historical industry perspectives on the international marketability of a particular series is a speculative undertaking, given that interviewing is impossible and most corporate archives are closed, leaving us to interpret those perceptions from extant comments in trade journals and marketing activities. Nevertheless, it seems clear that Warner Brothers did not have strong confidence in the sales potential of Roots. At the April 1977 Mip-TV international sales market, Warner Brothers representatives refused to report its sales figures to Broadcasting magazine, typically a signal that sales are poor. By contrast, MGM executives reported in the same article that their miniseries How the West Was Won, which had aired a month after Roots on ABC, had been sold to thirty territories (“U.S. as TV Programmer,” 1977). Most likely, the same doubts about Roots that executives at United Artists and Twentieth Century Fox had expressed earlier to Wolper also fueled concerns at Warner Brothers.

A comparison of promotional advertising for Roots designed for domestic and international buyers reveals uncertainty about how to frame Roots’ domestic popularity in a way that would appeal to potential foreign buyers, especially European public service broadcasters. While the ad designed for domestic trade journals emphasized the ratings performance of the miniseries in major markets, an ad in the April-May 1977 edition of Television International listed only the awards that the series had earned. The accompanying text reads, “Rarely has quality been so richly rewarded” (Warner Brothers, n.d., a). Apparently, Warner Brothers did not believe that the popularity of the series in the domestic market alone could guarantee sales abroad, and felt it necessary to emphasize the “quality” of the miniseries over its popularity. The international ad is an obvious attempt to counteract the belief that Roots was little more than a popular story for American viewers, but also a high-quality television series for the ages.

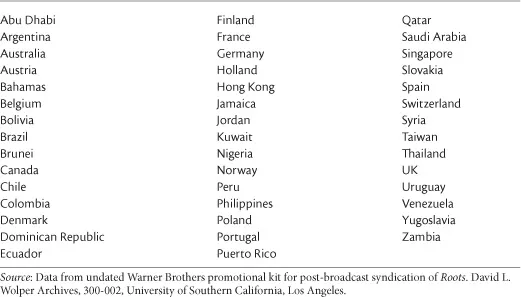

Table 1.1. Nations Importing Roots Prior to 1981

By November 1977, Warner Brothers reported in its internal corporate magazine Warner World that the miniseries had been picked up “in almost every major country in the world” (McGregor, 1977, 18). A couple of words in this quotation bear closer scrutiny, specifically the words “almost” and “major.” Even in internal promotional copy, the company cannot claim that every major country has purchased the series, or that many smaller countries had done so. One year later, Warner’s promotional kit for international syndication made a much stronger case, calling Roots “the world’s most-watched television drama” and listing forty-nine territories that had purchased the miniseries (table 1.1).

Warner Brothers’ apparent lack of confidence in Roots suggests that its executives bought into the industry lore that African American dramas could not sell well internationally, especially when we compare their efforts with the confidence that MGM expressed toward How the West Was Won, a historical miniseries set in the American frontier in the nineteenth century and focused on white American rather than African American historical experiences. This industry lore was summed up succinctly by an anonymous network executive who told reporters five months after the blockbuster success of Roots that

the same white viewers who enjoy black ethnic comedy shows just aren’t about to accept a black hero in a serious dramatic program. If it’s not a comedy, they just won’t accept it. And the economic realities we live by tell us that we can’t exist by appealing to only a black audience. (Deeb, 1977)

It is perhaps not surprising that prevalent industry lore in the late 1970s militated against exporting narratively complex, dramatic stories about African American suffering during slavery. Television merchants, after all, are not primarily cultural theorists, but businesspeople, and as such they cannot be expected to know the common experiences and bonds that non-Europeans around the world share due to the history of colonialism. They are, however, cultural interpreters who decide which projects will get production funding based on estimations of their potential international sales revenues, which programs will get heavy promotion at international trade shows like Mip-TV, and how those programs will be positioned via advertising in relation to other programs on the market. In the case of Roots, industry lore about the appeal of African American television complicated production funding, depressed international sales, and may have facilitated the spectacular portrayal of black male bodies.

Competition, Broadcast Economics, and the Rise and Demise of the Miniseries

Despite dominant industry perceptions that African American dramas could not appeal to white viewers at home, much less foreign viewers, a combination of forces led to efforts to develop the miniseries Roots in the late 1970s. These included technological, regulatory, economic, and cultural changes, specifically the deployment of communication satellites; the FCC’s passage of the “open skies” plan for satellites; the move on the part of television networks toward expensive, “prestige” programming; and the black revolution of the 1970s. Production costs for the miniseries genre, however, made it particularly dependent on international sales revenues, and ultimately undermined its viability.

Into the 1970s, the television broadcast networks faced little competition from cable and satellite programmers. Although the technology of cable dates back to the beginnings of nationwide television in the United States, cable was used primarily for rebroadcasting network programs, rather than carrying original cable programming. Similarly, communications satellites began broadcasting nationally and internationally in the 1960s, but the FCC stymied development of that industry as well, in order to shore up the incumbent broadcast networks. By the mid-1970s, however, broadcast network power had begun to erode. The Nixon administration’s famous disdain for broadcasters led to an opening up of competition early in the decade, in particular the open skies policy, which freed any company to operate, uplink, and downlink satellite television services. As a result, Time Inc. launched the first satellite and cable network, Home Box Office (HBO), which transmitted a combination of movies and sporting events. HBO was joined by the nation’s first superstation, WTCG (soon to be renamed WTBS and later TBS), in 1976, which programmed a combination of sports and network reruns. The networks could see the handwriting on the wall, and began to focus on the kind of prestige programming events that only they could afford, in order to price any potential competitors out of the running for top prime-time audience ratings.

Miniseries had the added advantage that they ran during sweeps weeks, the monthlong periods during which the A. C. Nielsen Company tracked audience ratings at local stations in order to set advertising rates for the upcoming quarter. Sweeps weeks are notorious for the stunts that programmers pull in an effort to artificially raise viewership; miniseries became an effective tool in these efforts. Finally, throughout the 1970s, competition between the three major U.S. networks had grown increasingly fierce, as ABC continued to siphon viewers away from the traditional leaders, CBS and NBC. In 1976 ABC finally toppled their dominance and became the top-rated network for the first time in history (Quinlan, 1979).

Miniseries also offered the networks an opportunity to portray socially relevant and politically dicey programming, much like the movie-of-the-week genre, which attracted both critical acclaim and affluent urban viewers. While “relevance” had become a buzzword among network programmers since the debut of All in the Family in 1970, the concept had begun to disappear from regularly scheduled weekly series by the middle of the decade, replaced by what were derisively referred to as “jiggle” series aimed at youthful viewers, such as Three’s Company (1977–1984) and Charlie’s Angels (1976–1981) (Levine, 2007). These series were less likely to worry advertisers but performed as well among audiences as relevant programs. Additionally, changes in the cultural mood o...