![]()

1

Introduction

Taking Criminology to the Movies

What is the relationship between criminology and crime films? What kinds of intellectual enterprises occur at the intersection of criminological theory and cinema? What sorts of encounters might occur were criminology to go to the movies? These questions lie at the heart of this volume.

Theory—whether it be theory of crime or of the image—has a bad reputation. Students often find theory dry and abstruse, and they discover that it is difficult to relate theory to practice. Scholars are in part responsible for theory’s bad reputation, for too often they take a narrow and rigid view of theory, positioning themselves in relation to a particular set of propositions that they then spend their lives elaborating. But theory, as we understand it, is exciting terrain—dynamic, fluid, plural, accessible, and part of the lives of ordinary people. In other words, theory is not confined to academic criminology. Criminological theory is at work all around us—in daily conversation, news media, prime-time television, music, cyberspace, mystery novels, and film.

In this volume, we begin with the assumption that criminology is hard at work in culture and that culture is hard at work in criminology. To illustrate this process, we focus on the cultural site that exemplifies this engagement perhaps better than any other—Hollywood cinema. We hope to show how ideas about crime develop in the cultural imagination and, in turn, shape and are shaped by theory as well. We argue that criminological theory is produced not only in the academic world, through scholarly research, but also in popular culture, through such vehicles as film. Our goal is to reconceptualize criminological theory in relation to culture—and, in particular, cinema.

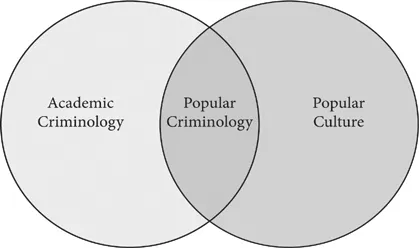

This book builds upon an article in which criminologist Nicole Rafter asserted that crime films play an important role in relation to criminology, constituting a “popular criminology, a discourse parallel to academic criminology and of equal social significance.”1 Here we set out to examine the space where popular culture and academic criminology meet (see Figure 1.1). We are not merely interested in showing how crime theories constitute a subtext in many films. We are much more interested in demonstrating that popular culture can expand formal theory—and that the encounter of theory with cinema is an engagement that leaves both fundamentally transformed. Using crime films to investigate the overlaps of criminology and popular culture, we analyze how these domains interpenetrate and cross-fertilize one another.

Figure 1.1. Popular Criminology: Where Academic Criminology Meets Popular Culture

In what follows we first discuss how academic criminology can benefit from closer connections to popular culture. Next we address the compelling role that crime plays in the popular imagination and ordinary life. The third of the following sections is devoted to a discussion of popular criminology, the innovative discourse that emerges from the intersection of academic criminology and popular culture. This chapter concludes with an overview of the volume and a note on the topsy-turvy manner in which the book can be read.

Academic Criminology

“Academic criminology can no longer aspire to monopolize ‘criminological’ discourse,” write two of the field’s most sophisticated observers, “or hope to claim exclusive rights over the representation and disposition of crime.”2 Yet most academics who write and teach about causes of crime ignore popular culture, perhaps because they do not know how to conceptualize their relationship to it. Others use film snippets in classes or write about cases famous in popular culture—but without theorizing the interrelationships between the examples and scholarly work. At the same time, specialists in popular culture, while increasingly engrossed by criminological matters, lack a conceptual scaffolding for bridging the two fields. This volume shows how to deal with such problems through a move beyond descriptive efforts toward a rigorous theoretical interpretation of popular culture. The first question in such a pursuit is one for academic criminology, and it is a question of the image’s significance: Why take seriously “criminology in the image”?3

The first and foremost answer to this question is found in the overwhelming presence of crime in popular culture. To ignore cultural representations of crime is to ignore the largest public domain in which thought about crime occurs. (In fact, if our diagram were drawn to show the relative importance of the two domains, the circle on the left, representing academic criminology, would be the size of a pinhead, while the circle on the right, representing popular culture and its ideas about crime, would fill the page.) But academic criminology has been slow to focus on popular culture, and it has tended to push such inquiries to the margins of the field.

To be sure, some criminologists have engaged with aspects of popular culture.4 For example, some have conducted psychological studies of media effects, examining the impact of violence in representations on violence in real life.5 Others have studied the role of media-amplified moral panics, episodes in which the media suddenly define a group previously regarded as harmless as a social threat.6 A far more profound and theoretically fertile engagement with popular culture appears in the recent work of cultural criminologists, who examine the intricate media environment of a globalized, late modern world.7 Given the unprecedented and all-encompassing role of media in contemporary life, cultural criminologists are critical of an older idea that “pictures” show “reality,” which in turn affects social action and crime policy through direct lines of causality. Older “gap” studies focused on discrepancies between images and what they purported to represent—as, for example, when scholars examined ways in which films inaccurately depicted police corruption or women lawyers. In the view of cultural criminologists, in contrast, “the media is no longer something separable from society. Social reality is experienced through language, communication and imagery. Social meanings and social differences are inextricably tied up with representation.”8 But even within cultural criminology, film analysis has lagged behind studies focusing on television, print news, and mystery stories.

In bringing film analyses forward in criminology, we hope to expand criminology’s boundaries, laying the groundwork for engagements that extend beyond past and present theoretical understandings. For example, many criminologists reject psychological explanations because they focus on individual, rather than social, factors in offending. However, psychological explanations circulate widely in crime films, serving as a cultural resource for viewers working through issues like the responsibility of the mentally ill offender, the role of science in court, and the advisability of behavioral modification as a tool for social control. As we show, films like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Fritz Lang’s M (1931), The Boston Strangler (1968), and Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange (1971) illustrate problems in not only psychology but also psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Many films depict the interplay of multiple and sometimes contradictory psychological impulses. While a psychological study must examine mental abnormalities and discuss variables in a scientific register that often obscures this complexity, film allows a broad public to explore and develop positions on the value of psychological perspectives on crime. Recognizing how cinema extends criminology into the realm of the psychological moves us well beyond debates about, for instance, the effects of media violence. These discussions also alert us to the reality that psychological theories of crime circulate broadly and deeply in the cultural imagination, regardless of criminology’s distance from these perspectives.

Cinema also serves as a popular source for articulating, modeling, and critiquing theories in ways that academic criminology often cannot. Attention to these possibilities initiates interdisciplinary alliances and promises a more democratic, less exclusionary view than that of academia of what it means to do criminology and be a criminologist. Taking criminology to the movies fosters theoretical development. If criminology accepts the validity and necessity of the kinds of analysis we propose here, the stage will be set for new questions about crime and its explanations to emerge.

Popular Culture

Clearly, it has become increasingly difficult for academic criminology to maintain boundaries between itself and popular culture—to ignore the explanations of criminal behavior generated so powerfully and prodigiously by movies, novels, television, and other cultural discourses. Most impressive is the fact that criminology has managed such a feat as long as it has, given crime’s ubiquity in popular culture.

Academic criminology can do many things that popular culture cannot, such as discovering the prevalence of specific crimes, the effects of drugs and alcohol, and why people may be reluctant to report offenses to police. On the other hand, popular culture brings to discourses about crime some attributes that scientific criminology cannot claim. One of these is an ability to speak to diffuse cultural anxieties. There is a quality—or texture—to crime and victimization in everyday life that formal criminology and other social scientific studies miss. As numerous “culture of fear” studies point out, popular fascination often revolves around the anecdotal, the violent, the sex scandal, the serial killer, the child abduction and murder.9 From novelist Truman Capote to television crime journalist Nancy Grace to the television show Law and Order, graphic and detailed accounts of crime pervade everyday life. Dismissing these accounts as voyeurism or schlock limits our understanding of their social functions. Instead of ignoring or correcting these spectacles, we ask how such cultural focal points are relevant to criminology.

Even more pertinent is the fact that one cannot really pull apart image and meaning. We are not claiming merely that movies create cultural focal points and reproduce the emotional textures of crime in ways that formal criminology cannot. Rather, we are claiming that images organize our worlds and that representations are central to our lives. Representations shape how we think about crime and formulate public policy. Our beliefs about serial killers and child molesters are closely bound to the images with which popular culture bombards us.

One characteristic of popular discourses about crime that is usually absent from academic criminology is its strong emphasis on emotive elements in crime—its adrenaline rush, pleasure, desperation, anger, rage, and humiliation.10 Film, unlike academic criminology, provides a broad window into the ways in which criminal behavior is shaped by values and emotional contexts. The same is true of film’s ability to make us aware of the emotions of victimization and even the experience of people who work in criminal justice professions. For instance, The Silence of the Lambs (1991) shows us the vulnerability, terror, and determination of FBI cadet Clarice Starling (Jody Foster) as she confronts first the masculine world of law enforcement and then the obsessions of two very different serial killers. Similarly, Thelma & Louise (1991) portrays the profound anger that fuels a crime spree after one of the women is almost raped. Films can vividly depict how people caught within worlds of crime and victimization cope and ultimately survive, for better or worse.

One of the most intriguing and troublesome developments in recent popular culture is the appearance of major films that blatantly defy criminological explanation. They have no heroes, and the crimes of their leading characters are either random or inexplicable. In films like Taxi Driver (1976), Mystic River (2003), The Departed (2006), Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007), No Country for Old Men (2007), and There Will Be Blood (2007), crime and extreme brutality are ultimately incomprehensible. These films show bleak, violent worlds where the villains often go unpunished and the innocent unsaved. A sense of desolation and loneliness drives protagonists toward transgressive and sometimes pathological behavior. Viewers are often left, as in No Country for Old Men, with no clear way of making sense of the criminal; such films challenge the very idea of criminological explanation. In other films, social order is cautiously reasserted but not without a sense of irony and despair, as with the ignominious death of contract killer Vincent (Tom Cruise) in Collateral (2004) or the sudden and strange celebrity of Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) after his murderous rampage to save a child prostitute in Taxi Driver.

This trend is associated with postmodernism, the late twentieth-century aesthetic development characterized by irony, fragmentation, instability, and playfulness about violence. It is also a trait of late modernity—the period in which we live—which is defined by a rapid global tempo that is often atomizing and isolating in its effects upon the individual. In this context, capitalism reigns supreme, inequalities flourish, and faith in progress has vanished. Future horizons are overshadowed by new and unprecedented forms of mass violence, war, and disaster, all capable of ending human life in apocalyptic annihilation.

Another by-product of late modernity is films with byzantine narratives and numerous major characters who intersect across a background of globalization. Traffic (2000), Syriana (2005), Crash (2004), and Babel (2006) depict disconnected lives of multiple characters, crisscrossing globally, their fates interwoven by invisible narrative connections. In this kind of film, characters’ lives are often marked by a sense of futility, moral ambiguity, and doubts about the possibility of justice.

Another way to think of these cinematic developments in popular culture is as part of an alternative tradition in Hollywood production, out of which emerges a new category of critical crime films.11 In contrast to conventional narratives characterized by easy resolutions, where heroes win out and villains are punished, critical films are dominated by open endings and characters who are neither good nor bad but inscrutable. In these contexts, the world, the self, and truth are volatile, unpredictable, and never fully knowable. Such tendencies in popular culture raise questions about the very possibility of theory.

Popular Criminology: Criminology Goes to the Movies

Popular criminology begins from the standpoint that crime films are integral to crime, criminology, and culture itself, comprising a popular discourse that must be understood if thinking about the nature of crime is to be fully understood.12 “Given the ascendant position of the image/visual in contemporary culture,” writes cultural criminologist Keith Hayward, “it is increasingly important that all criminologists are familiar with the various ways in which crime and ‘the story of crime’ is imaged, constructed, and ‘framed’ within modern society.”13 A popular or cultural criminology, by broadening the parameters of knowledge about crime and criminality, provides a point from which to develop a more contemporary set of questions foundational to the field. It promises simultaneously a more expansive and better unified body of knowledge about crime. What is most noteworthy about the comments of Hayward and other recent writers on representations in criminology is the manner in which they call for reinvention, for research on crime that can bring together theory and image. They all assume that in order to do criminology, we must pay close attention to the act of representation.

Popular criminology, as criminologist Eamonn Carrabine points out, is in the air, with growing attention from scholars working independently of one another.14 Rafter’s article provides a useful starting point, defining popular criminology as

a category composed of discourses about crime found not only in film but also on the Internet, on television and in newspapers, novels and rap music and myth. Popular criminology differs from academic criminology in that it does not pretend to empirical accuracy or theoretical validity. But in scope, it covers as much territory—possibly more—if we consider the kinds of ethical and philosophical issues raised even by this small sample of movies. Popular criminology’s audience is bigger (even a cinematic flop will reach a larger audience than this article). And its social significance is greater, for academic c...