![]()

1

Introduction

The gravitational theory of accountability has one central proposition: blame falls to the bottom, to the fall guy. When things go wrong with a policy, people try to shift the blame. Those best placed to do this are those at the top. Even when there is evidence of complicity at the highest levels of government, blame will find its lowest plausible level. When the news of abuse or atrocity hits the front page, leaders faced with managing the blame are likely to react in a self-interested and opportunistic way and seek to deny and evade accountability. It is a rare leader who acts differently. Despite our reflexive association of democracy with accountability, our institutions provide poor compensation for such human failings and blame-shifting forces. In arguing for this simple proposition, this book places political and military leaders at the center of the explanation of how democracies manage the blame for atrocities. It has modest expectations about their motives as they adapt to the demands and pressures of their political environment.

Individual motivation is more complicated than is assumed here. This explanation has, for example, no place for some internal moral compass setting leaders on a course for truth and responsibility. All the same, it is worth seeing how far such a simplification can take us. If an explanation of this sort works anywhere, it is going to work in the less sentimental sectors of human interaction, the for-profit or for-power sectors, and when the expected consequences are very serious, which is the case with a government’s use of violence and killing of civilians.

The central concern of the book is how leaders in democracies have managed the blame for killing civilians and for violations of human rights and humanitarian law committed by their armed forces. The argument that democratic leaders behave in an opportunistic rather than a principled way and manipulate the institutions designed to deliver accountability is counter to the conventional wisdom. If accountability is to be found in any country’s politics, it is to be expected in a country with stable democratic institutions and free and independent media. Accountability is the guiding principle of a representative democracy. At elections, voters can hold leaders accountable for their performance in office. Between elections, internal systems are in place for monitoring and punishing decision makers. These systems either separate power among institutions so that each watches the other or fuse power so that government decision makers are routinely responsible to their colleagues in parliament. As one of the foremost scholars of political leadership says, “a democratic process is a pragmatic way to ensure that modern leaders enter their position with a firm claim of legitimacy and can be held accountable once they get there.”1 It does not happen with human rights violations.

With either a presidential or a parliamentary design, this book argues, political leaders manage the blame for doing wrong in armed conflict in a similar way. They do not submit an honest account of what happened. If they are forced to acknowledge the action, they shift blame for it to the lowest plausible level. As a consequence, and despite the general claim that accountability is a central feature of democracy, it is not delivered when it is most needed and where it might be most expected—where the rule of law and long-held moral prohibitions against killing and abusing civilians are at issue.

The failure to deliver accountability must have been apparent to Baha Mousa’s father when he received the news of the one-year prison sentence given to one soldier for beating his son to death. In September 2003, Baha Mousa was taken into custody by British soldiers in Basra, Iraq, and beaten over a prolonged period, apparently out of earshot of the officers in charge.2 The failure of accountability was evident to survivors of a massacre in Beirut by an Israeli-armed militia in 1982, to the families of the British citizens shot to death in Londonderry in January 1972, and to the survivors of a protest in the Punjabi city of Amritsar in the spring of 1919. All must have harbored doubts about democratic promises concerning the rule of law.

Hypocrisy aside, these types of events tell us a lot about how things work. They are difficult to foresee and have a galvanizing effect on political actors. As a consequence, when they make the headlines, they put decision makers and political systems under sudden, extreme stress, yielding information on the performance of individuals and processes. The process of accountability normally includes information on what happened, an evaluation of wrongdoing if any, and consequences for those responsible.3 Yet, despite the academic and political significance of this topic, there is surprisingly little work on violations of human rights and the subsequent processes of accountability in full democracies. There is a literature on truth commissions that other political systems have employed to resolve conflicts.4 There are accounts of democracies imposing accountability on others, as at Nuremberg, and there is work on apologies and the treatment of the past.5 There is some general literature on how politicians manage the blame or the placement of responsibility for the harm done by their decisions or actions. The literature includes work by the philosopher J. L. Austin and the political scientists Morris Fiorina, Christopher Hood, Kathleen McGraw, and Kent Weaver, but there is not much to be found on blame management in the areas of armed conflict and human rights violations.6

There are other ways to think about these issues. There is a strong tradition in the study of international politics for using ideas and values as a starting point. We might assume that politicians in democracies are motivated by liberal and democratic values and that they are responsive to concerned organizations such as Amnesty International.7 The fact that war crimes tribunals and inquiries take place may be pointed to as evidence of the impact of these liberal democratic values. The Israeli judicial inquiry that followed the massacre of Palestinians in Beirut in 1982 and other similar cases may be interpreted as suggesting the power of principled ideas.8 The literature on human rights protection is broadly consistent with this emphasis.

This literature is more attentive to the causes than to the political consequences of killing civilians or using torture on prisoners. In the effort to explain why countries display marked variation in their observance of human rights standards, this literature points to the presence of mechanisms of accountability and the importance of democracy. Research shows how important it is to have states committed to protecting human rights and to have citizens active in support of those commitments.9 The presence of elections and an active set of voluntary associations mobilized around human rights and civil liberties issues reduce the chances of torture and killing carried out by government agents. This combination of institutions and activity is what is meant by a mature liberal democracy. The most robust finding of this literature is that these types of democracy—not just systems that hold elections—are substantially less likely to commit violations. The interpretation of this statistical finding suggests the importance of accountability as a defining feature of such democracies: “Accountability appears to be the critical feature that makes full-fledged democracies respect human rights.”10 This book explores the limits of this assumption.

To take the ideal case as illustrative, a leader most firmly in the grip of principle would not explicitly or tacitly consent to abuse or atrocity in the first place and would take action to stop it and punish those responsible as soon as she knew of it. Such a leader would not require the goad of public outrage. The timing of the process of accountability is significant. With gravitational theory, the assumption is that it is the public’s knowledge, rather than the leader’s knowledge and commitment to the rule of law, that triggers inquiries and the downward shifting of blame. Blame for policy disasters becomes an issue only when there is pressure on public support and when the news of the event threatens to damage careers and reputations. In cases of human rights violations, it is a rare leader who acts to put his or her reputation at risk in advance of public exposure and on moral calculation alone. Yet, on occasion, I expect that gravity (not a technical term here) fails in the political world. After all, here we deal with individuals and choices, not with Newton’s apple. In the political world, gravity is a resistible, rather than an irresistible, force. Candidly admitting responsibility for the abuse or for failing to control those who committed the abuse and so inviting the blame is an option.

The political scientist Christian Davenport has disentangled the different aspects of accountability and examined their impact on human rights violations. One aspect is the dependence of politicians on public support in competitive and participatory political systems. This factor (“voice”) is more important than the particular institutional checks or constraints on the executive (“veto) in the political system. Davenport says that “when authorities are accountable . . . they are less inclined to use coercion against them because they could lose mass support, be removed from office, or face . . . some form of investigation.”11 These are important findings about what is likely to reduce the incidence of violations. My question concerns what happens under conditions where there are “voice” and “veto”—that is to say, under the condition of full democracy—in the unlikely event that violations do occur. Is accountability delivered? While a commitment to protect human rights and the presence of mechanisms for accountability matter in terms of reducing the likelihood of violations in the first place, after violations occur, expediency, not principle, dominates. It may be that leaders take responsibility for other types of policy disaster. Some scholars suggest they do: “In the end, buck passing only undermines one’s authority, whereas proactive and well-communicated responsibility taking serves to reinforce it.”12 It is an empirical claim. I suppose it depends on what they are taking accountability for and the precise meaning of these management concepts. There is no evidence that leaders submit timely and honest accounts (“proactive and well-communicated responsibility taking”) for policy disasters involving the security forces and the killing of civilians and the abuse of prisoners. And they tend not to be corrected by the electorate. Voters may punish politicians for their performance in other areas, for example, their management of the economy. But, at least according to President George W. Bush’s campaign strategist, the issue of war crimes was more of a liability for John Kerry in the 2004 election than for the president.13 Rather than the president being punished for violations committed by American soldiers, Kerry was punished for raising the issue of American war crimes as a Vietnam veteran.

So how do we sort out responsibility and punishment? What evasive tactics do we employ, and what signal do we send about our values and standards of conduct? How do we meet this test of national character? The argument in this book applies to democratic governments’ use of force, their adherence to human rights and humanitarian obligations, and the treatment of civilians and prisoners. It may extend to other sorts of policy disasters and other hierarchical institutions, such as corporations and churches and their unlawful activities. The concluding chapter discusses the limitations and extensions of the argument.

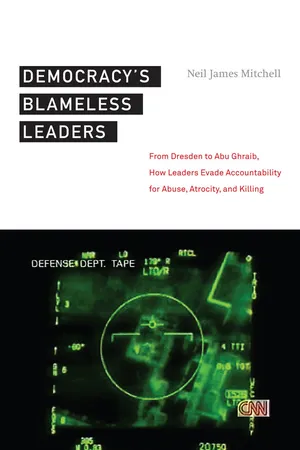

Shocking Events in Amritsar, Dresden, Londonderry, Beirut, and Baghdad

The overall aim of this book is to understand how leaders in democracies manage the blame when their agents commit violations. Examining the forces at work and thinking about why leaders let us down spark analytical curiosity. Analysis and an appreciation of the challenge that delivering accountability represents are the basis for reform and an antidote to the human rights hubris of countries like America and Britain. Recognition that democracy’s promise of accountability has systematically exceeded its performance in this area is important in itself. Only by considering a series of cases across time and political space is this recognition possible. Such recognition points the way to informed and perhaps more authoritative participation in the progress of the idea of human rights. At the same time, it is also helpful to say what the aim is not. The aim of the book is not to suggest that we should remain silent on human rights—or to make an argument that no one is good enough to speak to this issue. Nor is it to suggest moral equivalency. To take the most extreme example, Dresden does not bring into balance the inhumanity of the other side. Remembering rather than forgetting our own inhumane acts and the inadequacy of the response to these acts does not truncate all points on the worldwide scale of inhumanity to one value.

The cases considered in these pages stretch from the early twentieth century to the early twenty-first century. They presented leaders in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Israel with choices in accounting for what happened. This book examines the choices that they made and how accountability was delivered. These cases allow an initial empirical assessment of my argument and an understanding of the forces at work in managing the blame. Because they are relatively rare events and seem so extraordinary at the time, they have been left largely to historians. They are regarded as accidental to democracy. After the Beirut massacre, the Israeli government was said to be “still treating the entire affair as a freak historical accident or a matter of abominable luck.”14 There is, then, room to think about whether there is a connecting pattern of political behavior left by these “freak” events. Like the events themselves, the failures of accountability tend to be seen as isolated failures in an imperfect world, rather than as indicative of a systemic weakness.

The book does not include all possible cases of violations committed by the armed forces of stable, liberal democracies. Were this study part of a large collaborative research project, its empirical scope could be more extensive. Instead, the book pursues a case study approach appropriate for a theory-building effort. Case studies have the advantage of allowing more in-depth consideration of the forces at work. A disadvantage is that such an approach is necessarily selective, rather than exhaustive. That said, the criteria for selecting the cases are described, and, the theoretical argument, like any other, is subject to the collective efforts of the research process and to the identification of counterexamples.

I used several criteria in selecting cases. First, the cases are limited to what seemed at the time extraordinary violations involving killing civilians and mistreating prisoners that might be expected to result in calls for accountability. What was done by liberal democracies in Amritsar, Dresden, Londonderry, Beirut, and Baghdad violated long-established liberal norms against killing and abusing civilians and prisoners. These cases raise issues of humanitarian and human rights law. Whether a violation has occurred is contested, at least by the perpetrators. The cases concern the safety of the person as described in Article 3 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, on “right to life,” and in Article 5, on “prohibiting torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” Two of the cases predate the 1948 Universal Declaration. Yet, when those cases occurred, there were already in existence established principles of international law that prohibited killing civilians and abusing prisoners. The United States and the United Kingdom were state parties to the 1907 Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War. This convention prohibited killing, unnecessary suffering, and attacks on undefended towns, villages, or dwellings. It provided for the humane treatment of prisoners. Furthermore, the London Agreement of 1945, with its Charter of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, reinforced Britain and America’s principled commitments to the treatment of civilians and prisoners. The London Charter provided the standards for evaluating the actions and policies of Nazi Germany in its use of armed force. This Charter, using principles from the existing Hague and Geneva Conventions, took the important step of individualizing criminal responsibility for war crimes. Government office and purpose did not protect an incumbent from criminal charges. These crimes included “wanton” attacks on cities. The Charter’s description of crimes against humanity protected the state’s own civilians from the state. These crimes included “murder, extermination . . . and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war.”15 The Charter extended cover for the civilian population against inhumane acts for wartime and peacetime.

Beyond international agreements, the cases were shocking at the time. The Amritsar massacre was an appalling event even by the standards of colonial rule. As a cabinet minister, Winston Churchill condemned the inhumane act at Amritsar in what is regarded as one of his great speeches. His word was “frightfulness.”16 At the time of Dresden, Churchill was prime minister. These two cities provided quite different contexts for killing civilians. Suppressing colonial unrest inspired by saintly nonviolence is not the same as fighting a war for national survival against an enemy capable of anything. Yet, before Dresden, Churchill’s government concealed the nature of the bombing campaign from the British public. After Dresden, the prime minister used the London Charter’s word “wanton” to describe the Royal Air Force’s bombing of that city.17 Then he left Bomber Command and its commander to shoulder the blame.

The number of fatalities that occurred in the cases under study ranges from relatively few at Bloody Sunday in Londonderry to hundreds at Amritsar and in Beirut and up to perhaps twenty-five thousand in Dresden. Yet, all are of a scale sufficient to have been described as conscience-shocking at the time. While the cases under study do not include all possible conscience-shocking cases, those included are the ones that tend to come to mind in this regard (and not just my mind). For example, in discus...