![]()

1

The Syndication Market in U.S. Television

In syndication, programs are sold individually, market by market, meaning historically a series might play on the CBS station in Los Angeles, an NBC outlet in Detroit and an independent station in Nashville.

—Los Angeles Times television industry critic

and analyst Brian Lowry1

Highway Patrol was a gem. It was a terrible show. Broderick Crawford would get out the car and stand there and get the microphone and say, “10-4.” And then he’d put it back and he’d drive off. That’s the show. I’ve just given you a half-hour episode. But the audience liked it, so it was a gem.

—Dick Woollen, former vice-president, Metromedia2

It is much more fun to sell, because as buyers there is so much crap to consider.

—network executive at a Latino-themed cable network

who has worked both sides of the industry3

The global market for the export of U.S. television programming was launched in the mid-1950s by the big three domestic broadcast networks—first CBS, followed by NBC and then ABC.4 With airtime on newly established networks abroad needing to be filled, the market for the screening of “telefilms”—as the filmed series were called—outside the United States was thus realized. CBS, in 1954, was the first to venture into foreign distribution of its network programming with sales to other countries, with NBC and ABC following soon thereafter. Not only did the networks syndicate the programs they produced themselves, but they also syndicated abroad the series that were produced for their prime-time schedules by outside suppliers.5

The way the international export market that we know today emerged from the nascent television industry of the late 1940s and early 1950s was hardly the result of a well-developed business strategy for conquering the world. What eventually became a ubiquitous and popular form of entertainment abroad was, in its earliest version, a product that first had to be conceptualized, developed, and accepted in the United States by the industry, its audience, and government regulators.6

Commercial television broadcasting began in the United States in 1946, and a robust demand for programming to feed the burgeoning domestic market developed soon thereafter. In domestic television’s earliest years, regularly scheduled programming consisted of a mix of live-interview, variety, quiz, and sports shows, and dramas appeared only during the evening hours.7 As scheduling opportunities expanded to include daytime, late evening, and weekends, the networks scrambled to fill these additional time blocks.8

Live broadcasts were the preferred medium for the new industry, a taste that prevailed at the outset for several reasons. Chief among them was that recorded programs were not of good quality, and audiences that were used to decades of live broadcasts on radio were unwilling, at least initially, to modify their expectations. Another reason was that filmed programs could be distributed directly to local television stations and thus they represented a threat to the networks’ control over distribution. In short, filmed broadcasts were regarded by the industry and the viewing audience as less desirable fare than live programming.9

Filmed Programming Enters the Picture

The filmed programming that existed between 1946 and 1951 originated from a handful of independent production companies that operated on the margins of the industry. This market began as early as 1949–50 with the appearance of series such as Boston Blackie, of 1940s B-movie fame, and Hopalong Cassidy, a reedited version of the 1930s and 1940s films that first screened in theaters. In 1951 and 1952, more reputable production companies emerged, including enterprises such as Desilu, which produced the still popular sitcom I Love Lucy for airing on CBS, and Four Star Productions, which produced the anthology series Four Star Playhouse, also for CBS.10 Through diversification, coproduction arrangements, access to actors supplied by talent agencies, and creative financing, these companies came to dominate the industry throughout the 1950s.11 Their programming, which was originally produced for broadcast on the major networks, subsequently expanded to include series that were sold via syndication to individual stations or groups of stations in lieu of airing over the networks.12 Disney, in 1954, was the first of the major film studios to enter the television business. It wasn’t until 1955 that the other major Hollywood studios began producing original filmed series for television. By 1960, they provided 40 percent of network programming.13

Fig. 1.1. Prime-time schedule: fall 1947. Source: Brooks and Marsh, 2003, p. 1354.

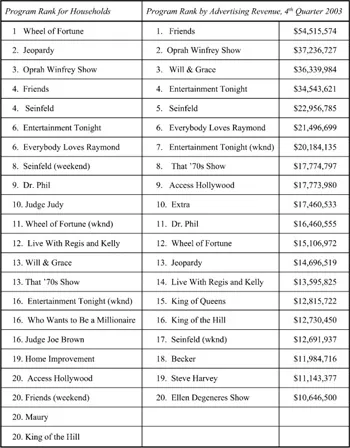

As the domestic television audience expanded, the emergence of independent (i.e., non-network-affiliated) stations generated a significant additional source of demand for filmed television programming. Independent stations had existed since the beginnings of television, with some of the earliest broadcast stations in large urban markets ultimately choosing not to affiliate with a network.14 Most stations with low bandwidth became network affiliated15 or, if they were in a large market, became stations that were owned and operated by a network.16 Owned-and-operated stations are required to carry the network’s entire program lineup, assuring the network exposure to all its offerings. Beginning in the early 1960s, the number of independent stations expanded considerably as high bandwidth was opened up by the Federal Communications Commission. According to Matelski, independent stations faced the same demands for finding prime-time programming as the networks did in the early days of television.17 To fill their schedules, they relied heavily upon in-house production, syndicated off-network shows, repackaged movie serials, cartoons, or movies from the Hollywood studios’ film libraries, and other similar kinds of recycled or independently produced filmed programming. Today’s syndicated offerings are made up of an array of updated programming options that include the genres of game shows, talk shows, off-network sitcoms and dramas, court shows, and weekly action/science fiction shows, as figure 1.2 reveals.

The Financing of Production for Network Series

From its very beginning, prime-time television production operated under deficit financing, meaning that series were produced at a loss relative to the licensing fee the networks were willing to pay for airing the series. Procter & Gamble, a leading program underwriter in the early days of television, established the practice of paying only 60 percent of the production costs of the shows it sponsored, an arrangement that led the owners/producers of telefilm productions sponsored by Procter & Gamble to seek other forms of compensation to recoup their losses, including reversion of syndication rights to themselves following broadcast in the domestic market. Once the networks themselves began commissioning series,18 they too adopted the practice of deficit financing, (i.e., paying a licensing fee less than the supplier’s production costs). This financial arrangement led independent production companies who licensed their products to the networks to seek ways to recoup their losses from expenses incurred. In particular, it encouraged producers to seek out the secondary markets, domestic and international, beyond the network for additional revenue.19 At the same time, due to the powerful bargaining position derived from control of the domestic prime-time schedule, the networks were often able to extract the right to sell those series abroad through their own syndication divisions.20

Fig. 1.2. Top 20 syndicated shows for September 2003 to January 2004 and their advertising revenue. Source: Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Monitor-Plus, Broadcasting & Cable, March 8, 2004, pp. 2A and 11A.

Regulations implemented in 1970 greatly expanded the participation of non-network companies, both large and small, supplying series to the networks under deficit financing arrangements. The Federal Communications Commission’s Fin-Syn Rules, instituted in that year to broaden the diversity of perspectives on the airwaves, placed strict limits on the amount of prime-time programming that could be produced by the networks themselves and prohibited them from syndicating the series they broadcast. In the Fin-Syn era, most prime-time pilots and series were supplied by independent writer-producers working for outside production companies that retained ownership and syndication rights; consequently, the financial viability of virtually the entire community of program suppliers depended on success in the syndication market. And, indeed, syndication became immensely profitable for program suppliers, so much so that the networks lobbied vigorously for the removal of the rules so that they too could enter this lucrative market. The rules were phased out beginning in the early 1990s, and today the networks compete alongside the major studios and independent production companies in the syndication market. Networks may now own unlimited hours of the programs they broadcast and syndicate them abroad.

The end of the Fin-Syn Rules also changed the nature of deficit financing, since the networks now receive revenue from both advertising and eventual sale of series they own in the syndication market. Deregulation prompted the trend towards consolidation between networks and studios and a corresponding rise in in-house production21 and direct participation by networks (via their parent corporations) in both domestic and global syndication. Program suppliers without an ownership relationship to a network are losing access to the prime-time network marketplace and to network licensing fees as a source of revenue.

The Prime Time Access Rule

Also implemented in 1970 was the Prime Time Access Rule, which further contributed to the expansion of the syndication market. Until 1970, “prime time” referred to the network-controlled broadcast period of 7:00 P.M. to 11:00 P.M. In 1970, the Federal Communications Commission’s Prime Time Access Rule imposed two restrictions upon the networks and their affiliates: the rule limited network prime-time broadcasts to three hours each night (with an extra hour on Sundays), and it prohibited network affiliates in the top fifty rated markets from running off-network programming (i.e., syndicated reruns). The intent of the rule was to give back an hour of programming each evening to the local network affiliates for community-relevant shows. However, affiliates rarely programmed that hour with this kind of viewing, and instead, audiences developed a taste for the kind of syndicated entertainment programming that was being offered in its place. “With these new incentives, syndication companies proliferated to provide competitive first-run shows, franchised programs, co-op productions, and, of course, the ever increasing numbers of off-network TV fare.”22

In sum, the market for syndicated television programming grew out of a need to fill ever-expanding program schedules at network, affiliated, and independent stations. The business considerations described above set in motion a quest to identify audiences, including audiences abroad, who were in search of additional choices for entertainment viewing. While syndicated television from independent suppliers originated to meet the networks’ need to fill their prime-time schedules, the networks soon developed a demand for programming to fill other dayparts—daytime, early evening, and the late-night portions of the program schedule. The proliferation of cable channels has only intensified the demand for such programming. Those seeking to deliver programming that would appeal to these audiences were necessarily dealing with issues of content as well as finance, and our study of the culture world of the industry attempts to understand the interconnection between the two.

As we will see in later chapters, this history of the domestic syndicated market is centrally relevant to the contemporary international market for television in several ways. First, syndication suppliers built a large stock of programming that was outside of the control of the major U.S. networks. Second, the market created a cadre of independent, entrepreneurial producers and syndicators who were unconstrained by the bureaucracy and regulation of the networks, and who were free to locate and cater to untapped audiences wherever they could be found. Third, the spot-market concept upon which the syndicated domestic market was based created a model of sales distribution that could be adapted to any locale, domestic or foreign. We turn next to the origins and development of this market to illuminate just how the syndication end of the business grew out of these conditions.

Selling in the Domestic Syndicated Market: The Early Years

The man credited with originating the domestic syndication business as it exists to this day is Frederic W. Ziv, founder of Ziv Television.23 Ziv’s background was advertising, to which he introduced an early form of product syndication on radio wherein he audiotaped radio programs for time-shifted broadcast, a process known then as “transcription.”24 Transcriptions made possible the live-on-tape concept that, with improved technology, eventually became accepted by an audience and an industry that believed broadcasts had to be consumed in real time, at the moment of production, as noted earlier. According to Ziv, in the earliest days of television there were only nineteen cities in the United States with television stations. That left the remainder of the country poised for station development, each with a need for programming. This, in turn, motivated Ziv to produce his own series for syndication.25

This new business opportunity gave rise to the need for sales personnel who traveled from station to station selling syndicated telefilms (or “telepix,” as they ...